corgan

A Prayer for the Day After Thanksgiving

November 29, 2013May we remember that thanks-giving isn’t a day or a celebration. May we remember that the act of giving thanks is a daily commitment, an intentional act of love, a spiritual practice of sorts, and an understanding that we are all a little broken, that we are all desperately in need of grace. The act of giving thanks is gritty and clumsy, awkward and vulnerable, constant and filled with kind truth.

May we remember that gratitude is a peaceful appreciation for the absolute privilege of life, with its inherent flaws, messiness, and organized chaos. May we remember that gratitude isn’t just obligatory thank-you’s for gifts and favors or bold professions of our blessings. Gratitude is a deeply felt inner truth, a delicate art form to be practiced, and refined over the course of a lifetime.

As we move further into the holiday season, may we remember that it is a season of gratitude, abundantly full of the connective fibers of life and the very essence of what it means to be alive.

Let Us Take Care of Each Other

November 15, 2013“I do believe we’re all connected. I do believe in positive energy. I do believe in the power of prayer. I do believe in putting good out into the world. And I believe in taking care of each other.”

Harvey Fierstein

Early this week, my youngest son came down with strep throat. Like most illnesses, it came at a rather inopportune time. We were out of town, a meeting was scheduled for that afternoon, and I had about a million other work obligations and chores that I should have been getting done.

But when my son awoke with a fever and complained of a sore throat on Monday morning, the schedule and to-do lists were thrown out the window. Adjustments were made. Plans were cancelled. Projects fell further down on the to-do list.

Instead of sticking to the plan and accomplishing what I had set out to do that day, I spent the day schlepping my kids to urgent care and the pharmacy, giving extra hugs, doling out medicine, and drying tears. Add a flat tire to the mix and the day just continued to unravel.

Throughout the day, one word kept coming to mind: unproductive.

I – like many others in our technology-driven, multitasking, busy-is-a-badge-of-honor society – tend to measure the value my day through the yardstick of productivity. How much did I accomplish during the day? How many items were crossed off the to-do list? How work obligations were met? How many projects moved forward?

We all have our own goals and dreams – not to mention our obligations and responsibilities – so we make our plans, write our lists, and schedule our days – and we should. Goals give us direction, helping us work to make things better. Schedules keep us on track, giving us a tool with which to allocate our time. Plans give our day and life purpose, creating a path to get from where we are to where we want to be.

But could it be that there is something more tucked away amongst all those plans and schedules and to-do lists? Could there be some quieter, calmer purpose hidden within all the busyness of our days and of our lives? Is purpose and achievement really meant to be measured by all that we accomplish in a day, in a lifetime? Or could our purpose actually be that we just take care of each other? Could our divine calling be something as humble, yet challenging, as taking care of each other in any way and whatever way we know how?

Does accomplishment lie in our own personal successes? Or does it lie in our ability to build someone else up so that they can achieve theirs? Does efficiency lie in a busy calendar, scheduled to the minute? Or does it lie in deeper relationships, a calmer mind, and knowing that we have made someone else’s day just a little bit better? Is productivity measured in the number of completed projects and tasks accomplished? Or can it be measured in back rubs and uplifted spirits?

I know myself well enough to know that I will always rely on my lists and my plans. I will always strive to be busy, to be doing more. And I will forever have projects, goals, and agendas. I will always strive to be productive.

As individuals and as religious communities, productivity is not only worthwhile and valuable, it is also essential. In order to grow and learn, to do better and be better, to build bridges and promote social justice, we need to continually strive to move forward, accomplish the impossible, and aspire for the unattainable.

But, at some point, the how becomes more important than the what. As the ever-wise Maya Angelou has said, “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

So, at some point, while we’re busy making our plans and working toward our goals, as a beloved community and as persons of faith, I think we need to ask ourselves: How are we taking care of each other? Because that, my friends, is really the measuring stick that we should be using.

Finally back at home on Monday night, when I tucked my sick-but-on-the-mend son into bed, drawing up the soft covers and smoothing his tousled hair, I knew that by all objective measures my day had been highly unproductive. Yet, I also knew deep-down that I had accomplished more in that day than anything that I could have put on my to-do list.

Still later that night, my husband came home from his own busy, hectic, and stressful day, filled with his own important meetings, difficult clients, and an ever-growing to-do list. He spends workdays being productive (in the objective sense) and providing for the family (in the traditional sense). Nonetheless, when he walked in the door that night and hugged me long and hard, when he said “I’m sorry you had a rough day” and then listened attentively and sympathetically, when he smoothed my hair before I fell asleep, I knew in my heart, that those minutes were – by far – the most productive and purposeful things that he possibly could have accomplished in even the busiest of days.

So here is an item that we should all put on our to-do list, today and every day: Take care of each other.

It’s that simple. It’s that hard. It’s that important.

A version of this post originally appeared on the author’s website at www.christineorgan.com.

The Language of Faith

November 1, 2013

Source: Google Images Creative Commons

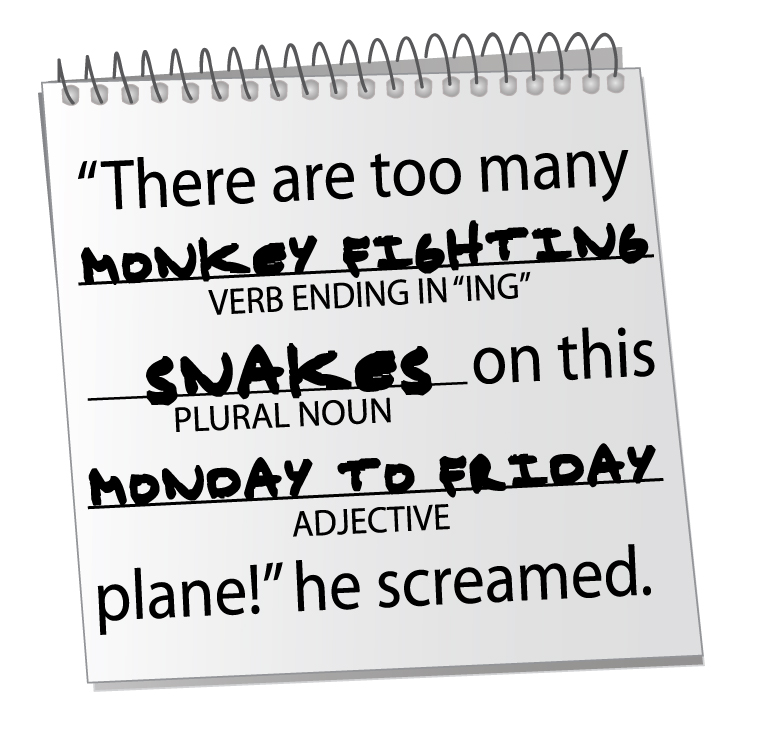

Last Sunday, while out to lunch with my husband and two young kids, we passed the time waiting for our food by playing Mad Libs. As you might remember, Mad Libs is a word game where one player asks another player to provide a particular kind of word – noun, verb, adjective, etc. – to fill in the blanks of a story. After the words are provided, randomly and without context, the other player reads the funny and often nonsensical story aloud.

If you have ever played Mad Libs, you know just how important grammar and semantics are to the art of storytelling. You also realize just how important words and context are to communication and understanding.

Words are, obviously, incredibly powerful tools. We use words to communicate, to connect, to explain, to inform, and to educate. But words have significant limitations, as well. Unfortunately, all too often words are used as a weapon instead of a tool. We use words to restrict instead of expand, to assume instead of discover.

Ironically, we often try to use language to define those things that are undefinable. We try to explain the inexplicable with rational, but overly simplistic, definitions. We fit people into our prepackaged labels –believer, nonbeliever, Christian, Jew, Muslim, atheist, humanist, idealist, pacifist, liberal, or conservative – and we try to make sense of this crazy, nonsensical, Mad Libs-like world with assumptions and categories.

But when it comes to the Big Questions, to matters of the Heart and the Spirit, there are no definitions. There are no labels. There are no prepackaged boxes.

Quite simply, language fails us when it comes to matters of the Spirit. God (I use the word “God” knowing that the word itself has its own limitations) comes in many names and is experienced in many ways. God and all things Spiritual, by their very nature, are unknowable and personal; they are felt with the heart and cannot always be adequately explained with words.

But, being the intelligent humans that we are, we try to explain that which is deeply felt with words, explanations, and sound bites. And, as a result, any inherent commonality to our human spirit gets lost, the beautiful complexity of differences gets diluted. The words – and labels – that we use become more important than the ideas.

So much division and dissention is created and exacerbated by the labels and linguistic limitations that we put on matters of faith and spiritual belief – concepts that are, quite frankly, too big to fit into any label or verbal representation.

Perhaps, we need to focus less on the words of faith and more on the language of faith. Perhaps we need to stop getting lost in the semantics of God and, instead, learn the languages of God – ones that are spoken and heard in a number of ways.

Music has always been my language of God. I love to sing (off-key) and can clumsily tap away a few songs on the piano, but I am far from what you would call “musical.” Yet music has always been a profoundly moving spiritual experience for me. Whether I’m swaying to a church choir singing “Amazing Grace,” listening to Bon Iver on my iPod, singing along to Bob Dylan in the car, or dancing like crazy with my kids in the kitchen, few things have the power to move me like music. Music creates an internal communication with the Spirit that washes my soul clean, as if I have stepped into a warm shower with the lyrics and melody rinsing away the grit and grime of everyday life.

Spiritual language can be found in any number of ways. My grandpa spoke the language of God through his generous hospitality. It was nearly impossible not to feel like THE most important person in the world when he greeted you. Others feel the language of God through the earth and nature. Gardening, for my paternal grandma, was so much more than a household chore, it was a spiritual practice unto itself. With her fingernails soiled and her hands calloused, as she tended and cultivated, she spoke a spiritual language that only her soul understood, that only her Spirit could appreciate.

Some people speak God’s language through art or poetry, photography or painting, teaching children or caring for animals, caring for the sick or sharing a meal with friends. Shauna Neiquist wrote in Bread and Wine, “When the table is full, heavy with platters, wine glasses scattered, napkins twisted and crumpled, folks askew, dessert plates scattered with crumbs and icing, candles burning low – it’s in those moments that I feel a deep sense of God’s presence and happiness. I feel honored to create a place around my table, a place for laughing and crying, for being seen and heard, for telling stories and creating memories.”

Let’s face it, we live in a chaotic world, where the unimaginable meets the incomprehensive, and devastating realities mix with everyday miracles. We want to make sense of it all. Of course, we do. In our well-intentioned, but misguided, attempts to explain, understand, and communicate, we look to definitions and labels. We rely on assumptions and suppositions, and we look to linguistic placeholders to meet the expansive scope of faith, God, and the Spirit.

We try to define the indefinable.

But maybe if we spend a little less time focusing on definitions of God and labels of faith, and instead focused on feeling the complex languages of God, maybe then we could gain a better understanding of each other and ourselves.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210