LeoCardez

Convict Chronicles: the stories that save us

December 10, 2023

Leo Cardez

CLF member, incarcerated in IL

“Corners,” my newest celly, is middle-aged and polite — the sort of man who carries the normal toil of the world. We have a lot in common and often spend hours talking about this or that. He’s easy to talk to, quick to grin with a wry sparkle to his eyes when he shares stories that are close to him.

Neither of us are much for idle chit chat or gossip, but occasionally we open up about our fears, hopes, and dreams and it can be quite powerful. I can always tell when he’s getting into a story, he leans forward pinning me with the force of his words. Stories of his past life, pre-prison, are tinged with regret; nothing more so than the loss of his daughter. She’s not dead, but when he came to prison in many real ways he died to her. Prison is certainly a type of death. Are we buried yet undead or are we dead yet unburied? She was only 8 years old when he came to prison and he still recalls her bright pink pajamas with the footies she was about to outgrow in another growth spurt. In fact, he told me, there has not been a single minute in a single day since he left that he hasn’t thought about her — not a moment has slid by when the world was not still oriented toward her. His words shook me to my soul. The depth of his tragic story of multi-generational addiction and abuse pinched the oxygen from the air. Yet, by all measures, it was clear to me he had learned to use his grief as a weapon for his faith and inner recalibration.

I see myself in all his stories, it is as if I’m speaking through him, only the names and dates are different. I suppose that is the purpose of good storytelling: be tiny and epic at the same time. The best stories are local slices of Life. They concern the neighborhoods where we grew up, our closest friends, and favorite things. They are close to the bone, the flesh of our lives. And yet, they are universal, too, because they speak to our shared humanity; the fears and hopes we all share as sons, brothers, fathers, and friends. Stories of prison woes, I’ve learned, are very similar regardless of age, nationality, or culture; what happened to one, happens to all.

Corner’s story is rooted in suburban privilege, but the story arc plays out similarly around the country’s prisons: an unfair criminal justice system, fear, loss, and the desperate attempt to find and hold onto hope and purpose in our cold, austere world.

It is an undeniable truth, when we open our hearts to hear each others’ stories — we oftentimes find ourselves in them; we realize we are not so different after all and others’ experiences can become our own. I’m confident employing shared storytelling as part of a larger restorative justice effort, connecting victims and offenders, would certainly break down barriers, shatter stereotypes, and be a conduit to true healing. But, that’s a bigger story for another time.

“There is no agony like leaving an untold story inside of you,” Zora Neale Hurston wrote in Dust Tracks on a Road. That quote is the principle that guides my writing. As much as my writing may have a self-help angle or sense to it, what I really want to impart is the human pulse of the stories. The essence of their message is that we’re all in the same boat just trying to get through this harder-than-we-could-have-ever-imagined thing called life. We need, nay, we must, share what we’ve endured as a means of catharsis and connection. I’ve often encouraged my fellow inmates to write their story. I believe everyone in prison has a novel inside of them waiting to bloom, if only they’d sit down to write it.

Corners’ stories keep unfolding, every one as poignant as the last and as we get to know each other the recitation and exchange of these stories is where the common ground begins to emerge. It is how respect and friendships are built.

My greatest fear is that my own daughter may follow in my addiction footsteps. I’ve read that young people today have the highest rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide in history. Many experts believe they are symptoms of a generation being raised during the digital revolution. As connected as the internet has the capability to make us, apparently today’s youth has never felt more alone and unheard. Stories are unfolding in them and they need to express them. I encourage my daughter to seek help, if and when she feels she needs it; to talk about her feelings. And she does. She’s putting cracks in the emotional walls that hold her hostage, so eventually the whole thing will fall. That’s what happens with enough time and pressure, even the hardest rocks will eventually turn to dust. But, the waiting and continuous effort needed to break down the walls is what is heartbreaking. But, that’s why we must continue to share all those stories we keep hidden in secret chambers of our hearts — they are what make us and what may save us all.

Writing My Wrongs

September 1, 2023

Leo Cardez

CLF member, incarcerated in IL

There is nothing exactly like living in Hell, but there is something close to it: jail and prison. In my hell, where I lived for most of 2015, there is, as Dante understood, no hope. People think the worst part of being locked up is the loss of freedom. They are wrong. The worst part is the loss of hope and purpose. You wake up every morning realizing your nightmare will continue into your waking hours. The loss you have suffered is permanent. Life will never be the same. In many real ways you are already dead, just unburied. There is no healing, no improvement, but even worse, there is no possibility of any to come. The most unbearable thing about your unbearable life is that you will always be forced to bear it.

In the midst of my horrific incarceration experience, alone and desperate to stop hemorrhaging relationships, I wondered if those who hated me were watching somehow they might find my misery satisfying? I might have, if I believed everything that was said about me. On a particularly dark evening, I considered doing

just that. I doubted anyone could despise me more than I did myself —

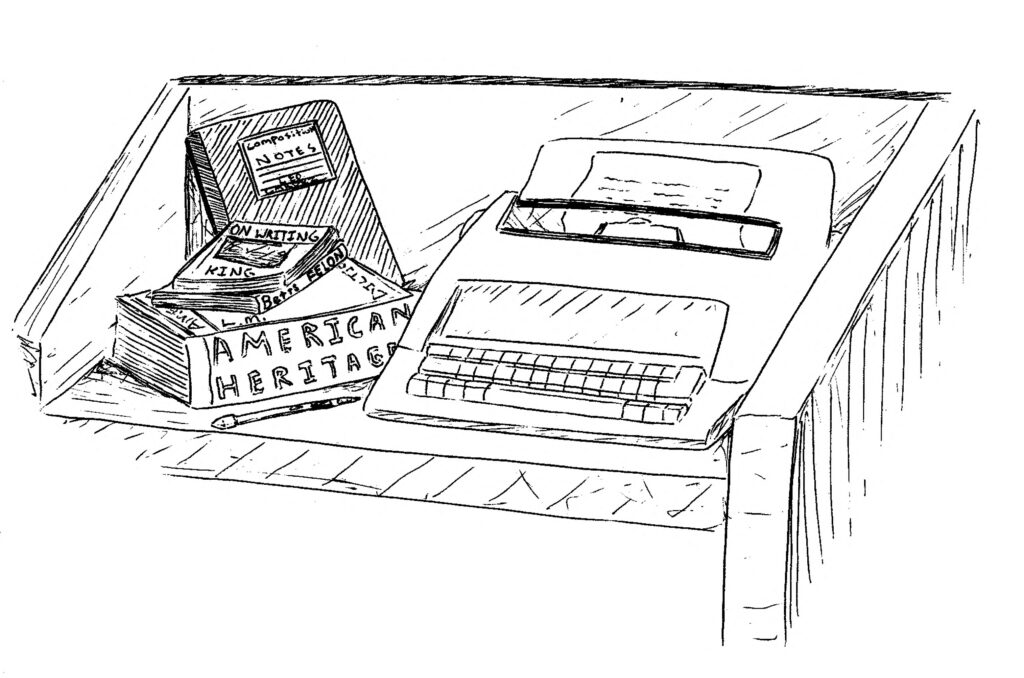

I couldn’t even stand my own reflection. But one can only fall so deep into the well before being consumed by the darkness. I admit, I considered the coward’s solution, but in writing my final note, I could not find the right words to convey the magnitude of what I was feeling. I refused to settle and postponed my act of desperation another night. Night after night I tried, but there were no words big enough… Instead, I found myself simply journaling about my day.

I wrote about everything and nothing, whatever popped into my head. My only rule was raw honesty. I figured if this was to mean anything to anyone it must above all be true. I didn’t realize honest writing will tear your guts out. Like when I wrote about the shame and pain I saw in my mother’s eyes when she came to visit me in prison — knowing it was my fault, and worse,

I could do nothing to help her. That feeling of helplessness was like being stuck in a barrel at the bottom of the ocean with no options. There is nothing worse.

Still I wrote. Everyday. I wrote by the light of the morning sun through my dirty cracked window or glare of the hallway lights through my cell bars. I promised myself I would write every day, no excuses… and I have. Now, 7 years later, I have learned that writing to me wasn’t a diversion, it was my church. It offered salvation in the promise of change. Escaping Hell is difficult because sometimes there are too many people who enjoy seeing you there, but with enough effort, grace; and in my case, pens and paper, it can be done.

As I re-read some of my earliest journal entries, I marvel at the flawed, petty, unhappy person I was. I also noticed that as my writing evolved into a more positive realm, so did my actual life. My writing became prophetic. As I tried to make the best of things, every now and then, I succeeded. As I look around today I can see that writing has helped me appreciate life in a whole new light.

When my parents wrote to tell me they were proud of me, even as I sat in prison, I am not ashamed to admit: I wept. I cried again after my sister’s last visit, seeing her changed and beautiful from the inside out; having found what she had been searching for, though not in the places she had been looking. I owe all of it to the power of the written word. It has taught me how to look inward in order to look forward. It has provided me with the key to an escape hatch to the next chapter of my life.

Renew Your Membership

We invite you to join your fellow CLFers to renew your CLF membership and stewardship of the CLF for another year.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210