rgallogly

Love at the Center: Exploring the New UU Values

January 10, 2024

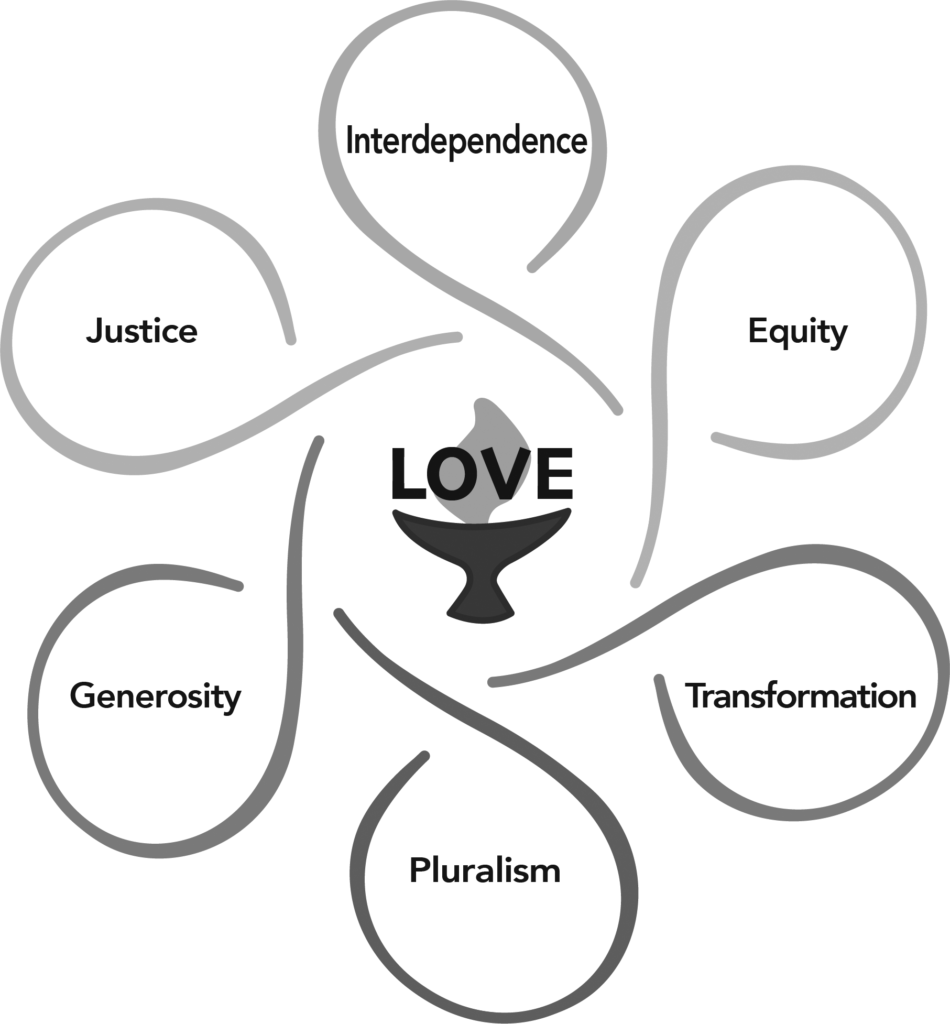

From the Article II Study Commission Report: a visualization of the new proposed language for Article II, defining six Unitarian Universalist Values, with the value of Love at the center. Design by Tanya Webster (chalicedays.org)

If you’ve been tracking the next 6 months of Quest themes, you may have noticed something: we’re using these themes to explore the Values of Unitarian Universalism, as articulated in the proposed new Article II of the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA) Bylaws.

In the February 2022 issue of Quest, in an article titled “Embracing the Living Tradition,” Rev. Michael Tino introduced these new values and the process through which they may be adopted by our Association. During the 2023 UUA General Assembly, delegates voted to move forward with the proposed language; there will be a vote during the 2024 General Assembly on whether or not to adopt these as the official articulation of our shared faith.

We’re looking forward to exploring how we relate to and understand each of these values over the next six months. As Rev. Michael wrote last February: “One of the defining characteristics of our Unitarian Universalist faith is that ours is a ‘living tradition.’ We do not etch our faith in stone precisely because we hold sacred that it must change. It must adapt to new challenges, it must meet new understandings, and it must evolve based on new experiences and connections.”

As beloved as the Principles of Unitarian Universalism have become in the almost 40 years since they were adopted, working with these new values is an important way to lean into the promise of our living tradition.

For those of you who will be submitting reflections for upcoming issues of Quest, I invite you to consider these values through the particular lens of how they may shape our shared faith. If the new Article II is adopted as our official faith language, that is the next phase of work ahead of us: to continue to co-create this faith with these values in mind, shaping and expanding their meaning by how we live them together. I’m so looking forward to being in that work together.

Turn the Year Around (A Winter Solstice Story)

December 20, 2023

Artwork made by Rose Gallogly for the pageant version of this story, performed by the children of Theodore Parker UU Church (West Roxbury, MA)

Part I: the beginning of things, when cycles are born

When the world was very young, there were not yet any seasons. There were not even any days — the Sun and the Moon shared the sky in harmony, quietly watching over the world together. After time had been passing for some time, the Sun suddenly realized that he was tired.

The Sun said to his friend the Moon:

“Moon, I have realized that I am tired, and would quite like to rest. What if we traded places here in the sky, so that we each get a break from watching the world, and have some time to rest?”

The Moon thought this was a wonderful idea, so they tried it out: each taking a turn to watch over the world in the sky, while the other rested. This is how the day and the night were born. This new cycle suited the Sun and the Moon very well — so well, that they decided that they each wanted their own larger cycles, in addition to day and night, so that they each had more time to rest and be renewed.

The Moon decided that she would wax and wane, showing up a bit less each night, until she was able to take an entire night off, and then come back slowly until she was in her full, beautiful glow. And so the months were born.

The Sun decided that he wanted a longer cycle: he would go to sleep just a bit earlier every night and wake up a little later every morning for six months in a row, and then, more fully rested, he would start getting up earlier and staying up later for the next six months. And so the years were born.

The Sun and the Moon loved their new cycles even more than they had loved the days. So much more felt possible in the world when everything worked in cycles. In fact, the Sun and the Moon felt so energized by their rest times that they decided they were ready for more life to join the world: in each new cycle, they introduced a few new beings. One new being at a time, they added mountains and rivers, trees and mushrooms, grasses and flowers and animal beings of all sorts. After many, many cycles, the world was full of beautiful new forms of life.

Each time a new being was introduced to the world, the Moon whispered to them: remember always that this world works in cycles. There are times of great light and activity, and there are times of darkness and rest. This is the great rhythm of the world, and all beings must follow this pattern in their own way.

The mountains and rivers and trees and mushrooms and grasses and flowers and animal beings of all sorts followed these instructions, and they each found their own cycles. And for a time, all was well.

Part II: Squirrel arrives, disrupts the cycle

The world continued on for some time, with the mountains and rivers and trees and mushrooms and grasses and flowers and animal beings of all sorts living on, each in their own cycle. Things were going well, so more and more creatures were added to the world: now the world had Owl and Crow, Deer and Spider, Hedgehog and Fox and Bunny Rabbit. Some beings struggled more than others to learn about the rule of cycles, but especially by the time the year got dark and cold, they always seemed to find their natural rhythm.

One day, Squirrel was born. Squirrel was small and fast and so happy to be in the world. He was so excited, in fact, that when the first instructions from Moon were whispered in his ears, he didn’t quite absorb them — he was already scampering away, running up the nearest tree to explore and learn as much as he could about this new world he had found himself in. The other animals saw this, and it worried them a bit, but little Squirrel was so cute and inquisitive, they all figured that he would learn the way of the world sooner or later.

Squirrel arrived in the world on the summer solstice, when Sun was at his brightest and most full. Everything was blossoming and bursting with life, and Squirrel saw that the world was full of abundance. Even though every day after Squirrel was born, the Sun went to rest a little earlier and woke up a little later, each change was so small and Squirrel moved so quickly, that it was many months before he fully noticed what was happening.

A few months in, the days had become darker and colder, and the trees had started to shed their leaves as they prepared to rest for the darker months of the year. Squirrel finally noticed these changes, and one day, he asked Owl (who had been around for many years, and always seemed to have the answers) what was going on. Squirrel asked:

“Old Owl, why have the days become so dark and cold? The world had such abundance and warmth when I first arrived. Has something gone wrong?”

Owl replied: “Oh little Squirrel. Did you not listen to Grandmother Moon when you arrived? Our world works in cycles — the Sun and the Moon each rest in their turn, and so must we. There is abundance also in our rest.”

Squirrel heard what Owl had said, but quickly dismissed it. Squirrel was very young, after all, and had some of the arrogance that often comes with youth. He thought, “Surely that only applies to the old beings who have been here for many years — I don’t feel tired at all! I’m so small and quick, I’m sure I’ll be able to zoom right through this cycle thing without missing anything while resting. I’ll stay awake all the way through these long nights and soon enough, the Sun will be back to brighten the long days again.”

The days kept getting shorter and the nights kept on getting longer, and most of the beings in the world watched this great cycle turning and responded in their way. Many of the trees shed all of their leaves, and the plants closed up their flowers. Crow and Hedgehog and Spider and Bunny Rabbit cozied up their homes and rested all through the long nights. Even old Owl, whose way was to stay awake through the long night and to sleep during the day, still honored this cycle in her own way: she grew a thicker coat of feathers to keep her warm in the beautiful cold and dark world.

But Squirrel, in his youthful arrogance, did not respond to the cycle’s turning. Squirrel pretended he was not cold and did not grow a warmer coat, but instead kept on moving so quickly that no other creatures could keep track of where he was. And even though it should have been Squirrel’s way to sleep through the long nights, he kept himself awake, wandering far and wide when he really needed to rest.

Finally, the world got to the longest night of the year, the turning point in its cycle, and the Sun went down for his deep, restful sleep. The Moon, who lived on her own cycle, was up full and high in the sky that night, watching over all of creation, as she always did.

As the Moon watched the world that night, she was pleased to see so many beings still following her important first instructions: some were awake, as was their way during the nighttime, and many were resting, as was their way. All seems well as the night went on and the Moon made her way through the sky.

Then, when the night was almost over, the Moon spotted something strange: there was little Squirrel, wearing much too thin of a coat of fur, and staying awake in hurried activity even though she knew full well that was not his true way of things. Moon suddenly felt a flash of anger that this being she had brought into the world was ignoring her instructions so fully! Were none of the other beings seeing this and helping him learn? In her anger, the Moon stormed away from the world — leaving the dark night without even the light of her presence. The Stars, who always watched the world kindly from their far-away homes, saw the Moon leaving and thought they should follow suit. The Sun, without the Moon returning to wake him and start the next day, slumbered on. So the world was left in darkness without Moon or Stars or Sun: the cycle of the year had stopped turning.

Part III: Squirrel learns to rest, everyone learns to turn the year around

It was Owl who noticed first. She loved the dark, so it was not the long darkness itself that she minded — but her heart felt it the moment the Moon and the Stars had left, and she knew something was wrong. There was an unnatural stillness to the world: the year had stopped turning.

Owl, even in all her wisdom, didn’t know what to do. The year had never stopped turning before! How could she call the Moon back and keep the cycle going?

Owl decided she needed help, not just from her animal friends, but from all of the beings of the world. She flew around waking everyone up: the trees and the flowers, the deers and the spiders, the mountains and mushrooms, telling all of them, “Wake up wake up! The Moon has left us, the year has stopped turning!”

Soon, all the beings were awake, disoriented and confused in the pitch darkness. Owl was trying to get everyone ordered, to see if they could come up with a plan, when she felt a little tug on her bottom feathers.

She looked down and saw Squirrel, small and tired and shivering in his too-light fur coat. Tears were streaming down his young face, freezing in the cold night air as they fell. He tried to speak, but words failed him.

Owl said: “Oh my dear, it can’t be as bad as all that! What’s wrong?”

Squirrel, speaking through his tears, said, “But Owl, it is, it is! It is all my fault that the year has stopped turning. The Moon saw me running around when I should have been resting… It’s because of me that she felt so angry that she left the sky altogether. I don’t know what to do!”

Owl sighed, and was still for a few moments. The poor young Squirrel in front of her was so very tired and distraught — Owl knew that more than anything, before anything else could happen, Squirrel needed to sleep. Owl thought back to her earliest days and remembered a song that a grandmother of some kind had sung to help the beings of the world learn to fall asleep.

Owl said, “Dear child. Rest now — the year has stopped turning, so really, we are in no rush. Let me help you fall asleep.”

And she started singing:

Return again *

Return again

Return to the home of your soul

Return again

Return again

Return to the home of your soul

The other beings who had been woken up in all of the commotion started to listen in — and particularly the older ones, who had been around in the very first cycles of the world, realized they knew the song too.

Return again

Return again

Return to the home of your soul

Return again

Return again

Return to the home of your soul

Before long, all of the beings of the world, all of the mountains and rivers and trees and mushrooms and grasses and flowers and animal beings of all sorts were singing. It felt right to all of them, somehow, to join together in song when the world was suddenly so strange and uncertain. Little Squirrel, who had been so very exhausted from trying to outrun the turning of the year, was soon fast asleep — but the other beings of the world kept on singing.

The sound grew so loud and resonant that even in her far-off place away from the world, the singing started to reach the Moon. She inched closer and closer until she could hear them clearly:

Return again

Return again

Return to the home of your soul

Then the Moon, the great grandmother of the world, realized: they were singing the song she had taught them! The anger in her heart started to soften, and she realized how hasty she had been to leave the world. After all, the beings she created were all still so young (that little Squirrel especially!) — of course they didn’t understand how very important cycles were yet. And now they were singing the very song that she had created to help them fall asleep! All was not lost after all.

And so, slowly but decisively, moving to the rhythm of their singing, the Moon returned to the world. She appeared again low in the sky, to the exact point she had left, just staying for a moment before going on to wake up Sun.

The many beings of the world, still circled up in song as all of them knew they should be as soon as they started singing, started to feel a lightness in their hearts. The sense of unnatural stillness began to shift. Just as the sun started peaking over the horizon line, they all realized together: the year had started turning again.

Little Squirrel, exhausted from his distress and his long refusal to follow his natural rhythm, slept for most of the month of this re-started year. When he woke up, the moon had gone through her full cycle, and was back in the dark, cold sky in her beautiful fullness. He saw her just for a bit, when she was low in the sky at the beginning of night. The young Squirrel was still moving as quickly as ever, but with purpose this time: he had much to gather to keep himself warm and fed before returning to a restful slumber for the rest of the night. Squirrel had found his natural cycles of things, and honored it as best he could. The Moon was glad, and she hummed an old familiar tune as she traveled, as ever, through her cycle in the sky.

All was well.

* “Return Again” by Shlomo Carlebach, Singing the Journey #1011

Return again,

Return again,

Return to the home of your soul.

Return to who you are,

Return to what you are,

Return to where you are

born and reborn again.

Samhain (Learning to Hold Ancestors Close)

October 1, 2023This piece was originally written and shared in October 2021 at my brick-and-morter congregation, Theodore Parker UU Church.

In the almost seven months since my beloved mother’s death, I have needed to learn the world all over again. Every seasonal shift, every holiday and tradition lands differently now; every detail of the world exists only in relationship with my grief.

When Halloween decorations started cropping up around my neighborhood this month, I realized that I was seeing the fake skeletons, ghosts, and gravestones — all of these casual references to death — entirely differently. It’s not exactly that I’ve minded that images of death on display around me, but more that I felt their irony in a new way. Halloween might be the closest this culture comes to having a holiday where death is on the surface, honored in some way, but even saying that is a stretch — this is a season of surface-level nods to death, with little space for holding its reality.

I don’t fault Halloween itself for this, nor do I begrudge my neighbors and the plastic gravestones on their lawn. The denial of death and grief in this culture is so much bigger than any one holiday. Modern Western culture, particularly white, mainstream Christian culture, sees life as an onwards and upward trajectory, and grief as a hard but brief, quiet, private time to get through. Even in this time of pandemic, in the mass death event we are all living through, dominant culture urges us to move ever forward, ever more quickly back to ‘normal’ — with little to no mention of our need to mourn the beloved people and things we have lost.

I’ve been feeling the irony of how we (sort of) (a little bit) reference death around Halloween particularly strongly, because the roots of this holiday offer something very different. Our modern Halloween has its roots in the cultural tradition of many of my ancestors: the ancient pre-Christian Irish/Celtic festival of Samhain (pronouced Sow-en), and its Christian equivalent of All Hallow’s Eve.

I’ve been interested in the culture and spiritual traditions of my ancestors for a long time; I see it as part of my responsibility as a white person to try to understand who my people were before we were considered white, and how the processes of colonization and assimilation brought us here. And now, as I try to process my grief, my interest in ancestral practice feels more like a longing, a need to be connected to a deeper sense of time, lineage, and culture.

So I’ve been exploring what is known about the spiritual traditions of my ancestors, including this ancient festival of Samhain, and trying to see what in those traditions might serve as antidotes for all that modern white culture lacks, particularly in relation to holding death and grief.

Samhain is known as one of the cross-quarter days in the Celtic wheel of the year, the approximate mid-point between the fall equinox and the winter solstice. It was a feast day, a festival to mark the end of the harvest season and welcome in winter’s darkness. The always-fluid boundary between the worlds — meaning the world of the living and the otherworld, where ancestors and other spirits dwell — was thought to be particularly porous around Samhain and the other seasonal festivals, like spring’s Beltaine; all times of great transition and liminality.

In contemporary pagan practice, Samhain is often referenced as a holiday about ancestors, a day to honor our beloved dead and perhaps feel closer to them than at other times. But much of my research suggests that seeing this as the one day to connect with beloved dead is more of a modern way of understanding the festival. Within the Celtic culture and worldview, ancestors were always present in daily life, and most major festivals honored and celebrated them in some way. Samhain has come to have a particular association with the dead simply because it marked the entry point into the winter, into the dark part of the year — and that whole season brought with it both a closeness to death, and more regular, ritual honoring of beloved ancestors.

I want to step back for a moment, and sit with that a bit more. Particularly if you are someone who knows and carries with you any kind of close loss — can you imagine how different it might feel to live within a culture were your beloved dead were held closely by your whole community at every holiday, and even particularly for a whole season of the year? A culture in which it was normal to speak their names, leave offerings for them, hold feasts in their honor, regardless of how long it was from their year of death?

Ancient Irish culture is, of course, far from the only culture to have practices of ancestor veneration, and to have holidays that honor the dead. I’m sure, actually, that in every one of our lineages, as close as in this generation or thousands of years back, we could all find traditions with deeply similar themes — because, of course, death is universal, and the need to honor it and tend to our grief is perhaps the most basic human need.

This is something I keep coming back to: these ancient cultural traditions of ancestor connection and honoring all come from the same universal human need to keep our loved ones close, especially when we are separated from them by death. Those traditions are now largely absent from our dominant culture — but the need for them has not gone away. Death is just as much of a reality in our lives now, it is simply less acknowledged; grief is just as present, it just less collectively held.

What would it look like for us now, in this tradition we are co-creating, to hold and honor our beloved dead together? Not just on this holiday, or even just this season, but all of the time? Informed by ancient practices or by simple human need, how can we begin, in whatever small way, to un-learn the death-denying norms of modern culture and embrace our ancestors once again?

Intro to the Special Edition: Quest for Seekers

August 18, 2023Welcome! Welcome to Quest, welcome to the Church of the Larger Fellowship, and welcome to Unitarian Universalism.

This is a special issue of Quest meant specifically for those who are new to the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF) and Unitarian Universalism, and want to learn more about both. We are a community of spiritual seekers: Unitarian Universalism is a faith bound not by dogmatic beliefs, but by a commitment to love, learn, and grow with one another. We learn from and are resourced by many different spiritual paths and wisdom traditions, and embrace theological diversity within our communities. Our shared beliefs center around love and liberation for all people, and a commitment to creating more justice in the world. If that intrigues you, keep reading.

In this issue you’ll find the guiding principles and values of Unitarian Universalism, a timeline of our congregation’s history, and more about our shared theological commitments. You’ll also see some testimonials from members of the Church of the Larger Fellowship, the Unitarian Universalist congregation behind Quest, about the impact that the CLF has had on their lives.

Regular issues of Quest include reflections on monthly spiritual themes, poetry and artwork from our members, and opportunities to engage with the life of our congregation. The CLF is a congregation with no geographical boundary, and Quest is just one way that we connect with our 3000+ members, more than half of whom are currently experiencing incarceration. Our members who have access to the internet can join our weekly online worship services, take classes and be a part of small discussion circles, and our members who are not online have access to correspondence courses, reading packets, and pen pal connections. Please visit our website or write to us if you would like to learn more.

We hope to connect more soon—until then, enjoy this introduction to our vibrant, liberatory faith community!

The Shape of Memory

April 1, 2022A phrase landed in me during the week that my mother was dying, as I grasped at any words I could find to make sense of the enormous shift in front of me.

The shape of every memory is changing.

I was seeing with painful clarity what anyone who has experienced big loss knows: I would now have two lives. The first life was the previous 26 years in which I was lucky enough to have my beloved mother with me in life, and the second, however much time I have in front of me, in which I would have to hold her close as a beloved ancestor. And every memory from that first life was now changing, shaped by the reality of this sudden ending.

My mother was a constant in all of the life I’d already known. Her steady presence, her love and care, was a backdrop to all things — a backdrop so fundamental to my experience of life that it was hard to see it clearly at times. Her love had always been at the center of my life, but I wouldn’t have named it as such until I realized I would have to live without her living presence reinforcing it. Perhaps that’s just the way of everything that is fundamental. We assume there will always be air to breathe, until there isn’t; we assume the sun will rise every day, until it doesn’t.

Now, the backdrop of my every memory was suddenly shifting into focus. Now, in the constant foreground: the gift of having had my mother for any time at all, my gratitude for any moment we spent together in life. The shape of every memory had changed.

So many other things have come into clearer focus along with that shift. There is painful truth to the cliche that major loss makes you realize what’s most important. I’ve moved through the past year with much more clarity about how I want to use my time and energy, letting go of past insecurities and narratives that no longer serve me. With my mother’s love at the center, I understand the sacredness of my life more fully. The shape of my every memory has changed, and with it, the shape and direction of my life.

Memory is not static, an unchanging account of events and relationships and facts. It is the source of our meaning-making, a collection of threads from which we weave the narrative that holds our life. The shape and texture of our memories change along with us, as we need them to, to make sense of the ever-changing reality we are faced with.

Letting the shape of my memories change to foreground my mother’s love is one of the things that has saved me, that has made surviving this first year without her possible. How we remember matters — and the shape of our memories can shape our lives as we move through them.

May you each find a shape to your memories that allow you to move through loss and change with more ease. May you know, always, that you are loved, and let that holding shape all of your life to come.

On Grief and Embodiment

June 1, 2021Thank you to Rachel for your above piece, “Loss as a Gateway to Compassion” — this reflection is prompted by and written in response to your words. Read more →

Honoring a Year of Pandemic: Grief and Gifts

March 1, 2021Though the COVID-19 pandemic truly started months earlier, March 2020 was the month when its life-changing realities hit many of us in the US and other Western countries. Read more →

Renew Your Membership

We invite you to join your fellow CLFers to renew your CLF membership and stewardship of the CLF for another year.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210