Expecting the Unexpected

December 1, 2019Podcast: Download (Duration: 16:15 — 22.3MB)

Subscribe: More

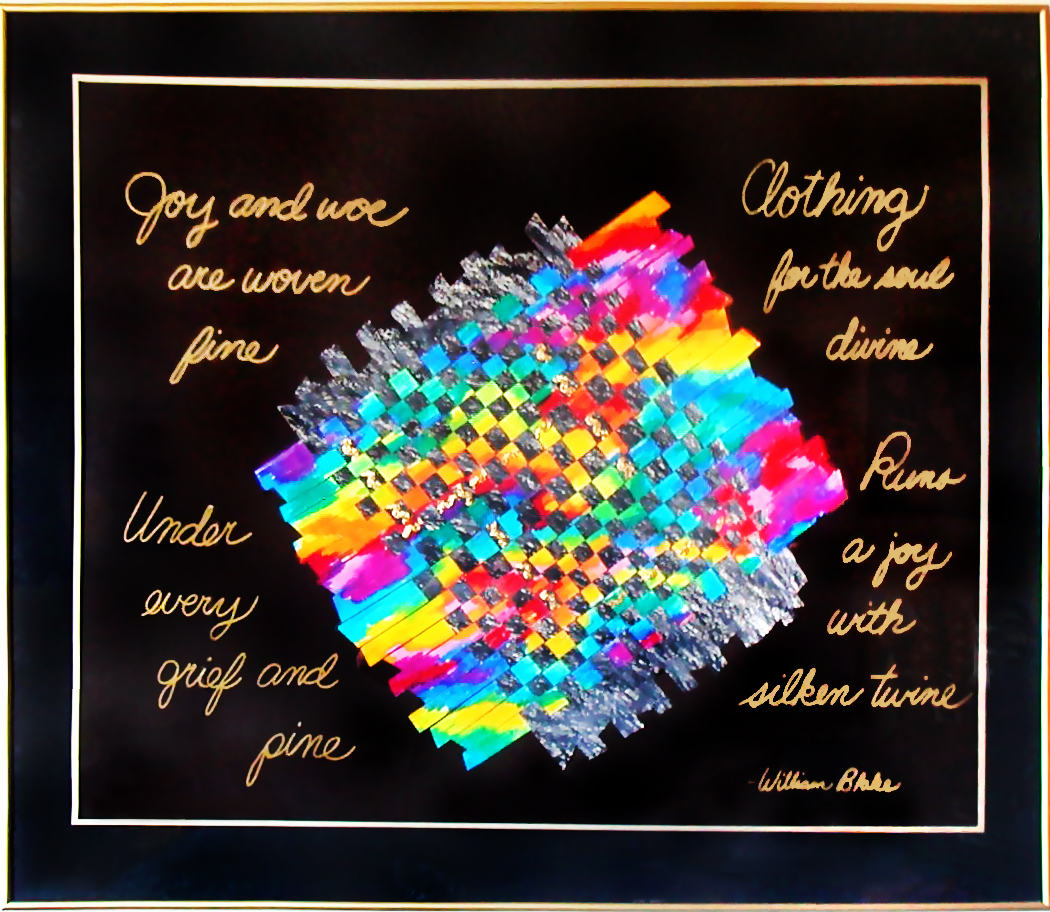

Joy and woe are woven fine,

Clothing for the soul divine:

Under every grief and pine

Runs a joy with silken twine.

It is right it should be so:

We were made for joy and woe;

And when this we rightly know,

Safely through the world we go.

—William Blake

…And the wicked witch turned into a toad and the evil sorcerer was banished from the land. The royal couple celebrated their marriage and were blessed with peace and prosperity and many children and lived happily ever after.

How many of us grew up with stories that ended something like that? First there was challenge and danger and hard work and then riches and blessings and happiness. The wicked were punished and the good were rewarded.

And then we discovered that life doesn’t necessarily work that way.

Twenty years ago, my life spun out of control. For some unknown reason, life started sending catastrophes my way, one after another. My life became a soap opera. Then it became too unbelievable for any self-respecting soap opera audience to swallow. I started to identify with Job. Then I started questioning whether Job had really had it that bad. Eventually I wanted to paint a warning message in huge letters on my wall: “Expect the Unexpected.” While I knew that this is impossible—if I could expect something to happen, then it wouldn’t be unexpected —the words captured how completely out of control my life felt. It seemed that the only thing I could do was to brace myself for the next crisis, to try to gather enough strength to ride it out.

Thankfully, my life has calmed down a bit since then, but I’ve been realizing that there’s more truth in that pithy saying than I realized when I wanted to paint those words on my wall. Because what got me through all the unexpected bad things was, in part, all the unexpected good things. I began to realize that expecting the unexpected didn’t have to mean bracing for the unexpected catastrophes. It could also mean keeping my eye out for the unexpected gifts, the silver linings.

Now, I want to be clear that I’m not suggesting that the silver linings in any way negate the bad, that good and bad can cancel each other out. Silver linings don’t make everything okay, but somehow they make good and bad less black and white, less absolute. A friend’s father told me a story about a conversation he’d had with his rabbi. The rabbi said that some good comes out of everything. My friend’s father was incensed. “What about the Holocaust?” he cried. “Surely you can’t tell me that anything good could come out of something so monstrous.” The rabbi paused and then responded. “Were it not for the Holocaust, your wife of forty years would never have emigrated to the United States to escape Austria and you never would have met her.” It’s not that this blessed meeting and marriage make the Holocaust any less horrific. That would be ridiculous. But, nonetheless, these two events are intertwined: out of an event that shadowed the twentieth century came at least one small blessing.

Expecting the unexpected is something we need to learn. It does not come easily. Most of us want life to follow the rules. We want the good to be rewarded and the bad to be punished. We want predictability and control. Sometimes we get to live with that illusion—we make plans and then we carry them out. The person who deserves it wins a prize. Hard work pays off. Good deeds are rewarded. And then there are the times when life appears to make no sense at all, when the walls come tumbling down and suddenly everything we’ve taken for granted is up for grabs. What then? What happened to happily ever after? Buddhism may be correct that the only constant is change, but that’s not always comforting when life seems to be coming apart at the seams. For me, one comfort is knowing that not all of the unexpected surprises will be bad. Sometimes, what first appears to be a calamity may turn out to be a blessing in disguise.

An acquaintance told me a story of a dismal time in her life. Her marriage had fallen apart. She was facing serious health problems. The future of her job was uncertain. Just as it seemed that her life couldn’t possibly get any worse, her car was totaled in a car accident. Cursing, she went to rent a car—yet another annoyance. How could she know that the man behind the rental car counter would turn out to be her future husband?

We do not have crystal balls. We cannot see into the future. What appears to be a curse may come with a blessing and what appears to be a blessing may come with a price. Meeting my late partner was clearly the best thing that ever happened to me. The five years we spent together were easily the best five years of my life. Watching him die was clearly the worst thing that has ever happened to me. Does the bad negate the good? Not on your life. Would I have traded the joy to be spared the pain? Not for a moment. Did I feel as though I was drowning in grief? Absolutely.

Sometimes it amazes me that the best thing that ever happened to me and the worst thing that ever happened to me were so intrinsically linked. But life is like that sometimes. Events are not necessarily good or bad. Sometimes they’re both at the same time. After my partner died, the Passover tradition of tasting the charoset and the moror on the same piece of matzoh—tasting the sweet mix of apples and honey and the bitter horseradish at the same time—made sense to me in a new way. Joy and sorrow can coexist.

A year of cancer treatment was not something I asked for, not something I would wish on anyone. Parts of it were pure hell. But at the same time it was such a rich year, so full of love and blessings and wonderful people and life lessons that I honestly don’t know if I would give it back if I had the choice. My cancer year wasn’t good or bad; it was good and bad, sometimes alternating, sometimes simultaneous. Charoset and moror.

Sandy Boucher, in her book Hidden Spring: A Buddhist Woman Confronts Her Life-Threatening Illness, writes about spending time in a large county hospital after major surgery and feeling overwhelmed by the sights and sounds. Desperately craving stillness, she feels assaulted by the loud voices and banging doors, the constant stream of medical personnel, her roommate’s many visitors and blaring television. Boucher’s friends pull the curtain around her bed to give her some privacy and one of them starts humming Amazing Grace, very quietly, to calm her. Suddenly, her roommate’s television set is turned off and she hears three women’s voices join in the song. The strangers in the next curtain have become earthly angels. The song is more beautiful, more precious for the surrounding melee. Boucher writes, “I felt as if I were being rocked and held in nurturing arms. . . Always there was some ray of kindness or beauty available to me, if I could be there for it.”

Shortly after this tsunami of calamities, I attended a week-long Art & Spirit retreat at a Quaker retreat center. During the opening activity we introduced ourselves by painting a crude image in primary colors on an altar cloth. As I sat there waiting my turn, I realized that I was feeling very peaceful—very happy and very sad at the same time. So I created a swirl of blue and yellow paint—yellow for happy and blue for sad, swirled together to show their coexistence. But I wasn’t content with my crude representation. This was a theme that I’d lived with for several years—that joy and sorrow can co-exist. How could I convey this in color and form? This question seized my imagination and would not let go. And thus I began a weeklong personal journey with sketch pad and oil pastels that took me far away from the regularly scheduled program of the retreat.

I wanted to convey the intensity of brief moments of joy amidst deep pain, but that wasn’t enough. Somehow I needed to bring to life the words of William Blake: joy and woe are woven fine. What would it look like to weave joy and woe? That was truly the question of my week and finally at the retreat’s end, I knew the answer. My clothing for the soul divine became a literal weaving of paper strips—charcoal gray interlaced with a vivid rainbow of colors.

I’m not trying to diminish the tragedies, not trying to say that everything will be all right. The pain is real. Bad things do happen. But it helps me to think of life as a rich fabric of joys and sorrows, successes and failures, gifts and losses, so tightly woven that sometimes the two extremes co-exist. And, in times of woe, it helps me remember to look for the silken twine.

We eat charoset with moror.

Life is not a fairy tale in which we live happily ever after. There will be happiness and there will be sorrow and they may even come as a package deal.

“We were made for joy and woe; And when this we rightly know, Safely through the world we go.

An East Coast transplant, Sue lives happily in Berkeley where she delights in the people, natural beauty, diversity of cultures, progressive attitudes, and plentiful fresh produce at the year-round Farmers Markets.

Sue’s essays have been published in Jewish Voices in Unitarian Universalism (“100% Jewish 100% UU”) and Faithful Practices:Everyday Ways to Feed Your Spirit (“Learning to Pray”).

Sue delights in spiritual practices – journaling, meditation, prayer, painting, singing, long walks in nature, stopping to smell the roses or really look at a tree.Perhaps her favorite spiritual practice is serving as a hospital chaplain, where she endeavors to listen deeply for what is needed in each moment and respond with love and compassion.

- Expecting the Unexpected - December 1, 2019

- The Ritual of Sabbath - July 1, 2018

- To Be a Blessing - November 1, 2017

Quest Monthly Print Edition

Recent Issues

Latest Spiritual Reflection Posts

Weekly Newsletter

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210