From Your Minister

July 1, 2019Podcast: Download (Duration: 6:34 — 6.0MB)

Subscribe: More

Out of your heart, cry wonder,

Out of your heart, cry wonder,

Sing that we live.

These are the final words of one of my favorite readings in the UU hymnal, “Out of the Stars,” written by Robert Weston. I love the words because they have a beautiful rhythm when you read them, a gait which seems to lift up the miracles that they spell out: That we exist! That we are connected to everything! That we love!

I have always been moved by those words because, for me, the stars are such an immediate and consistent source of wonder. Stars elicit mystery from our youngest age. Every two-year-old who speaks English learns that expression of wonder, Twinkle, twinkle little star, how I wonder what you are… a simple way of expressing wonder and awe.

One of the great blessings of stars is that they are always there, a constant. Even if it is a cloudy night and we can’t see them, we know they are there. Thousands of years ago our ancestors learned to follow them in order to sail, plant, migrate and mark earth transitions.

And even in this time when governments and corporations have devised ways to own rivers, oceans, airspace, water, even the very cells of plants and animals and our own bodies, no one has figured out how to own the heavens. (OK, I know, corporations are working on this in various ways, but they still haven’t gotten there.) Stars are there for everyone. They are there for the rich and the poor, people in refugee camps and prisons, people in slavery, right up in the sky shining their light on all who have a window to see out from. Sure, pollution may dim the lights in some places more than others, but no one needs to buy a ticket to look up. So they are present for all of us, in constancy and in radical egalitarian generosity.

And here’s another mystery—something scientists say which is so weird it’s hard to even believe—we come from the stars, all of us here. That’s not just poetry, it’s science!

Stars are in some cosmic sense our ancestors. We are stardust! This can give us a very big perspective on ourselves as humans—who we are and who we might be. It could fill us with pride, and it could also fill us with humility—are we manifesting stardust well? Are we shining radiantly, ever present for all? Imagining that we come from the stars can call us to enter the world of mystery and wonder.

Stars also call us to contemplate the mysteries of time and space. We might not be astrophysicists ourselves, but simply trying to understand how time and space are reflected in the night sky can be an exercise in profound and complex thought. Consider these words of Damian Audley from the “Ask an Astrophysicist” team, about how long it takes for a star’s light to reach the earth:

The nearest star to us is the sun and it takes about 8.3 minutes for its light to reach us here on earth, traveling at 186,000 miles per second.

Other stars are so much farther away that it is convenient to express the distance to them in units of the distance traveled by light in one year. This unit is called a light year. The next closest star to us is Proxima Centauri. This star is 4.3 light years away, which means that light from it takes 4.3 years to reach us. Our galaxy is about 100,000 light years across. This means that it can take tens of thousands of years for light from some stars in our galaxy to reach us. For stars that we can see in nearby galaxies it can take millions of years.

I don’t know about you, but imagining that I am seeing something that travels at 186,000 miles per second and still takes tens of thousands of years to reach earth completely boggles my mind.

But Audley isn’t done with the boggling. He continues: “The farthest objects we can see are quasars. They are so distant that the light we see from them today left billions of years ago. So when we look up at the stars we are looking back in time.”

We are looking back in time and we are looking across an incomprehensible amount of space! I have driven across this country and that has seemed like taking a huge amount of time to cover a vast amount of space to me, traveling by plane or train or car, none of which gets in the neighborhood of 186,000 miles per second. And yet, every time we look into the night sky, we are seeing this vastness.

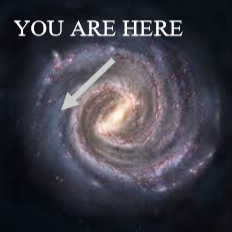

I used to have a postcard above my desk with a photo of the Milky Way galaxy, in all of its splendor. To one side, an arrow pointed into the midst of the galaxy with the words, You are here. When we see our troubles or worries with this kind of perspective, they seem very small indeed.

We can feel our very cells open, our body connect more deeply to earth, our soul begin to emerge from its hiding place, when we stand quietly under a night sky, take a breath, and pause. Stars connect us with both our own finitude and the world’s vastness. With both the edges of what we can know and see and the preciousness of that. With both the improbability of our life and the fact that here we are—out of the stars we have come.

- From Your Minister - July 1, 2020

- From Your Minister - June 1, 2020

- From Your Minister - May 1, 2020

Quest Monthly Print Edition

Recent Issues

Latest Spiritual Reflection Posts

Weekly Newsletter

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210