From Your Minister

June 1, 2018Podcast: Download (Duration: 6:34 — 6.0MB)

Subscribe: More

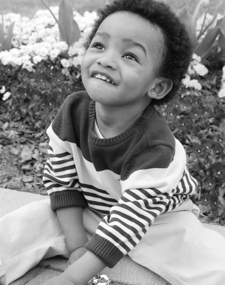

When my child Jie was 4, we were waiting in line at the post office behind a very dark-skinned man who wore a kufi cap, tunic and pants of a colorful African fabric featuring oranges, yellows and reds. My child looked up at him in wonder. “You’re beautiful!” Jie declared. And then, more thoughtfully, Jie asked, “Are you allowed to be beautiful?”

When my child Jie was 4, we were waiting in line at the post office behind a very dark-skinned man who wore a kufi cap, tunic and pants of a colorful African fabric featuring oranges, yellows and reds. My child looked up at him in wonder. “You’re beautiful!” Jie declared. And then, more thoughtfully, Jie asked, “Are you allowed to be beautiful?”

As I reflected on what might have caused this response, the intersection of race and gender, it seemed likely it was the man’s gender that caused Jie’s question. Jie’s pre-school teachers included several African women who wore traditional clothing, and Jie had never addressed them similarly. So a few minutes later, when we were outside, I asked Jie, “Do you think that men are not allowed to be beautiful?” And Jie replied solemnly, “Well, they never are.”

I’ve thought about this as we have deepened into this theme of beauty: Why it is that beauty is associated with the feminine and not the masculine? I asked several heterosexual women friends if they ever told their husbands or boyfriends that they were beautiful, and they seemed bewildered by the very question. They responded that no, they had not. Nor, they said when I prodded, did they think of these beloved men as beautiful. Handsome, sexy, all kinds of other things, but not beautiful. And when I asked why not, these women—feminist, thoughtful, women—said they thought it would be an insult to tell a man such a thing.

I guess we’ve decided in western culture that beauty is a feminine thing. Beauty is for women, not men, at least not cisgender heterosexual men. Not “manly” men. Beauty is…weak? A romp with my search engine instructs me that it’s OK to call pre-adolescent boys beautiful; after that they are handsome or good-looking.

This is perplexing to me. I think of birds; if someone says they see a beautiful cardinal or peacock, you can bet they’re talking about a male of the species. It is the male with the bright plumage, with the opulent beauty, while the females are more drab and subdued. Biologists think this may be so the males draw away predators’ attention from the females. In their case, beauty is a strength, indicating their willingness to give their very lives to protect their mates.

I also think back to decades ago when I studied the dialogues of Plato, and how often he spoke of beauty. In that completely male universe of ancient Greece that he wrote about, beauty was alive and important!

The readers of Quest are a diverse lot, and I’m sure people of all genders will agree and disagree with my assessment that men are, generally, “not allowed” to be beautiful. I am less interested in whether that is universally true than I am in why it would appear to be true to a four year old who was just beginning to tune into what gender and beauty mean in America. I am grateful that the gender revolution we are experiencing is affecting, among other things, our assumptions about what beauty means.

For most women, beauty is a form of tyranny. We are judged by our looks from the day we are born, and most of us know in exactly which ways we fail to measure up. Beauty standards are heavily determined by white supremacy: recently a magazine cover that purported to show the most beautiful women in the world showed seven reed-thin, blonde-haired, blue-eyed women who looked almost identical to the casual eye.

For me, at least, early adolescence was when these beauty standards felt the most assaultive, as I was beginning to see myself as a woman. Like many of my peers, I went to physically painful lengths to try to fit the molds which were not mine to fit—following preposterous diets, sleeping on orange juice cans to straighten my curly hair, slathering baby oil on my fair skin and burning it bright red to try to have a tan. Women of color I know have shared even more extreme pains they’ve suffered to try to fit beauty standards which left them out completely.

The theologian Carter Heyward said that homophobia is the club by which sexism is beaten into our bodies. As I look back to those years, any boy who looked anything remotely akin to “beautiful” would have been subjected to ceaseless ridicule, much of it steeped in homophobic slurs. While boys had role models to follow that were as impossible as the girls’, they were about courage or accomplishment, not about physical beauty.

What, I wonder, would it be like, if we had a standard of beauty that was accessible for everyone—all genders, all races, all kinds of bodies? What if TV shows and magazines were full of people noted for their brilliant smiles, the light in their eyes, the graceful curve of their shoulder? What if we had published lists of the top ten coziest laps for grandchildren or the Most Soothing Hands of 2018? What if we de-sexualized as well as de-standardized beauty, so that we could say to a co-worker “You look so beautiful with snow in your hair,” or to a child “You are so beautiful running across the soccer field.”

Perhaps we could not only give one another permission to look for and admire the wide range of beauty in the people around us, we could give ourselves permission to see and admire our own beauty, and to walk in the world conscious of the fact that we have beauty to share.

- From Your Minister - July 1, 2020

- From Your Minister - June 1, 2020

- From Your Minister - May 1, 2020

Quest Monthly Print Edition

Recent Issues

Latest Spiritual Reflection Posts

Weekly Newsletter

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210