From Your Minister

November 1, 2018Podcast: Download (Duration: 6:14 — 5.7MB)

Subscribe: More

One sentence launched me into discovery about my ancestors. It’s the first line of a book, Tearin’ through the Wilderness, which my great-Aunt Marie researched, wrote and self-published in 1956, long before self-publishing was a thing. Boxes of that book sat around in my childhood home, but I never read it until my Dad died and my siblings and I each obligingly took home the one with our name printed on the brown paper cover in my grandmother’s writing. My grandmother had inscribed one to each of us kids, but my father had never passed them on to us!

One sentence launched me into discovery about my ancestors. It’s the first line of a book, Tearin’ through the Wilderness, which my great-Aunt Marie researched, wrote and self-published in 1956, long before self-publishing was a thing. Boxes of that book sat around in my childhood home, but I never read it until my Dad died and my siblings and I each obligingly took home the one with our name printed on the brown paper cover in my grandmother’s writing. My grandmother had inscribed one to each of us kids, but my father had never passed them on to us!

Here’s how that book begins, written by great-Aunt Marie in the 1950s:

The Allen, Rives and Watkins families left a Virginia country environment where they were relieved of the drudgeries of workaday life by the labor of slaves.

The book then goes on to describe my ancestors’ decision in 1821 to leave Virginia and migrate west to Missouri, now that Missouri had entered the union as a state where enslaving other people was legal. My ancestors, and others they knew in Virginia, did their best to recreate the southern culture they loved, establishing part of the state still known as “Little Dixie.”

I grew up on stories of my brave ancestors heading west in a covered wagon. Indeed, “Covered Wagon” was one of my favorite games in childhood. Never had anyone mentioned the centrality of enslaved people to that narrative. If you’d asked me, I wouldn’t have even known that Missouri was a slave state. (Wasn’t it in the Union?)

We never had anyone play the part of enslaved people when we divvied up roles in the game of “Covered Wagon.” Yet those people I’d never heard about are absolutely central to my family history.

After I took in this new information about my ancestors, I wanted to know more. I took some sabbatical time to go to Missouri and to read everything I could lay my hands on about them. Luckily, my grandmother sent all of my great aunt’s papers to the Missouri Historical Society when Aunt Marie died. So there was a lot to read!

I also consulted some local history buffs who helped me figure out the location of the house my ancestors had built—as an exact replica of their home back in Virginia. Driving up to it, on beautiful rolling hills of fertile farmland, miles from the nearest town or highway, I was struck by how much it looked like the photographs I’d seen in my aunt’s book. Because I didn’t want to scare the current inhabitant, in case they were home, I went to knock on the door and introduce myself.

“Hello,” I began, when an elderly woman answered the door. “My ancestors built this house and…”

She interrupted me as if I had announced she won the lottery. “YOU’RE related to the Watkins, the Allens and the Rives!?” she shouted. “OH MY GOD!”

She invited me in. She got out her own battered copy of Tearin’ Through the Wilderness. She told me that the reason the house looked so much like the old photos in it is that her son and daughter-in-law had gone to Virginia and found the original house and modeled their porch on that house. She told me her late husband lived for a time with my late great-great uncle, a man I’d come to know through reading all the historical papers.

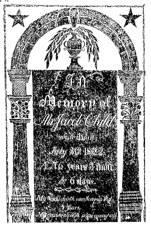

We were getting along swimmingly, though I knew this wasn’t going to last. I let it go by when she referred to a politician I admire with a racist derogatory name coined by Bill O’Reilly. She took me to the old family graveyard next door and I saw the gravestones of many people whose stories I’d been reading about.

Then her daughter-in-law, summoned to meet me, came over to the house. Another overtly racist comment was made, this time about recent protests in Ferguson, and I said, “I am sure we see many things very differently, but what you just said was very painful to me.” I then inserted a few sentences about the way I saw things—I figured I had just suffered through their interpretations and they would live with mine.

Conversation felt forced and strained after that, and I left before long. As I drove through the countryside on my way home, I reflected on the ways we are both keeping my ancestors alive. They are certainly more committed to that house than I am, and they know my ancestors’ names and stories at least as well as I do. Their current belief systems about humanity are more in keeping, probably, with the ways that my ancestors understood morality to function in the 1800s.

I am honoring my ancestors’ lives in a very different way. I am listening to their stories, coming to care about and even love them, and attempting also to be accountable for at least some of the pain and damage they inflicted. I’m allowing them to keep evolving and moving, though many of them died during and right after the Civil War.

I am taking them with me as I try to inhabit spaces of consciousness, accountability, and justice. I hope my own descendants will do the same for me!

- From Your Minister - July 1, 2020

- From Your Minister - June 1, 2020

- From Your Minister - May 1, 2020

Quest Monthly Print Edition

Recent Issues

Latest Spiritual Reflection Posts

Weekly Newsletter

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210