On the First Day

September 1, 2016Podcast: Download (Duration: 12:29 — 11.4MB)

Subscribe: More

Humans invent a lot of words to try to capture a bigness so large that we can’t fathom it. In English alone you’ve got gargantuan, humungous, enormous, gigantic, ginormous, vast. Those words are serviceable when we’re talking about an 18-wheeler or a blue whale or even Mt. Everest. But when we try to capture the size of the universe itself, words fail us.

Humans invent a lot of words to try to capture a bigness so large that we can’t fathom it. In English alone you’ve got gargantuan, humungous, enormous, gigantic, ginormous, vast. Those words are serviceable when we’re talking about an 18-wheeler or a blue whale or even Mt. Everest. But when we try to capture the size of the universe itself, words fail us.

Our universe is so big we really can’t begin to describe it or imagine it. Here’s how unimaginably big it is: when you look at those models of our solar system, they are never drawn to scale. Sometimes, if it’s a really big model, it can show the relative size of the sun and the planets to scale. But it would be really hard to make a model that would show the space between the planets to scale. If you made the earth the size of a pea, Pluto would be a mile and a half away and it would be the size of a bacterium. And that’s just our little tiny solar system.

What our universe consists of is mostly space. Empty space. Just enormity itself, with barely any content. It’s as if it only exists for the sake of its own size with just occasional little specs of matter incidentally sprinkled in. And we’re riding around on one of those little sprinkles, making art and killing each other and having babies and brushing our teeth, riding around and around and around, in an impossibly tiny bubble where life as we know it is precariously, temporarily possible. And the crazy, terrifying thing is, this is true. This is actually the way it is. Our reality is unfathomable.

From ancient times, people have looked up into the sky and wondered how we got here and how all of it got out there. They asked questions like, Why is there something instead of nothing? How did it come to be that this somethingness bloomed into salty oceans and islands and insects and sunlight and stars and dust and us? And why is it beautiful? They told stories about it and the stories evolved over the generations and they got passed down to us. The creation story that we know from the book of Genesis, told as a series of seven days, eventually got written down in Hebrew somewhere around the 6th century BCE and became part of what we call the Bible.

Listen to the very first sentence: “When God began to create the heavens and the earth, the earth was formless and void and darkness covered the face of the deep, and the spirit of God hovered over the face of the waters.” You might notice that this is different from how it’s usually translated. Usually it’s something like, “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” That’s the idea of creation ex nihilo (from nothing), which is usually the way it’s portrayed. There was nothing and then—boom!—God made the heavens and the earth.

But many scholars agree that the text really describes more of a pre-existing substance out of which God began to create the heavens and the earth. The words to describe that substrate are “formless” and “void” and “the deep” and “the waters.” So it sounds like it was a soupy, deep, formless Universe, completely dark.

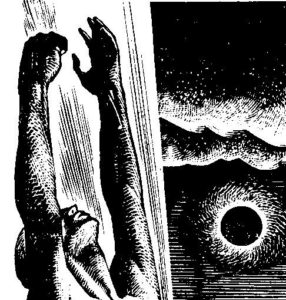

Picture this scene of the universe before the creation of heaven and earth—infinite formless and void dark liquid, darker than anything we’ve ever seen. And then the first act of creation: making light. Imagine what that would have looked like. Now we have the same primordial liquid soup, infinite in every direction, lit up with pure radiance. The light wouldn’t have been coming from anywhere in particular, because of course there was no sun or moon or stars yet, so that light would just be saturating the entire ocean of the universe with blinding luminescence. In the first instant of creation, this is what it would have looked like, according to this story we’ve received.

Now, I know I’ve said that this is theology, not science, but nonetheless, check this out. According to the astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, this glowing soup was, in fact, exactly the state of things the instant after the beginning of the universe. In his book Origins, he describes the universe when it was just a fraction of a second old as:

a ferocious trillion degrees hot, and aglow with an unimaginable brilliance…. For hundreds of millennia, matter and energy cohabitated in a kind of thick soup…. Back then, if your mission had been to see across the universe…you would have seen only a glowing fog in all directions, and your entire surroundings—luminous translucent, reddish-white in color—would have been nearly as bright as the surface of the sun.

Tyson says that this state of affairs lasted hundreds of millennia. But there’s a problem here: “hundreds of millennia” is a measure of time. It’s a number of years, and a year is a human concept—the time it takes the earth to orbit the Sun. What was time before the Sun or the Earth, or before anything to compare or measure one event against another? What is time without place? Without distance? Without any recurring event by which to anchor it? In a universe that is formless and void, is the concept of time even intelligible?

Listen to the next moment in the story: God separates the light from the darkness. And it doesn’t say that they were separated in space, like one half of the universe was light and the other dark. The implication must be that they were separated through time. The text continues, “And there was evening and there was morning, the first day.” So now picture it: we have the infinite primordial soup lit up and then dark. Lit up and then dark.

Through the creation of light alternating with dark, time was born. A differentiated “day” was now possible. Things could now happen in and through time; the stage was now set for the rest of the creation narrative and all the narratives of the future. Now there was a future and a past, a history of one day and a prehistory of hundreds of millennia. Without this checkerboard of light and dark creating time as it unrolled, the “formless and void” would have stretched out infinitely and eternally. But now stories—our stories—could begin.

The cycles of time can feel imperious and unyielding. We resist them. We resist change—we resist the next season, the coming of winter or the sweltering heat of summer. Most of all, we resist death. And yet it is these cycles of time that make meaning possible. Winter, spring, summer, fall. Light, dark, light, dark. Birth, death, birth, death. The cycles create a structure, an armature within which we thrive and within which we fall apart. Thrive, fall apart, thrive, fall apart.

Through time we measure our journeys, how far we’ve come since we were children. We remember love and love lost. We visualize a future of hope. The details of our lives unfurl within the matrix of our cycles. It is on time itself that we hang all our dreams. As much as we curse time, we need it. Without it, our lives would be formless and void.

So now we have this enormous, humungous, gigantic, ginormous universe, soupy and swampy, that has light and dark and time. But there’s one more crucial thing that happens on the first day. The text says, “God saw that the light was good.” This new entity of light is deemed good. God merely sees it. Recognizes it. Notices it. It doesn’t say that God made it good.

God saw that the light was good. It’s as if light’s goodness were somehow inherent. You don’t even need God for this light to be good.

Notice, also, that the text doesn’t say or imply that darkness was bad. Racism in our culture has twisted this text and created narratives where darkness is equated with black and evil, while light is equated with white and good. You see this violent trope in classic literature and in Hollywood to this day. So often the Bible is a Rorschach test. People use it to support narratives of existing power structures. But it seems clear that when the text here says “light,” it’s not talking about a color. It’s talking about literal light—the radiant, luminous energy that renders the world visible and warm.

We can draw hope from the knowledge that, if light is good, such goodness goes everywhere. We now know that it travels from stars 55 million light years away. It glows from phosphorescence in the ocean. It reflects off of the moon. It shines in wavelengths that we can’t even see. Light fills every available space. Every nook and cranny is infused with it. Everything that we know and love is blessed by its touch.

So this yawning expanse of vastness that we call our universe is full of something after all. It is full of goodness. It is inherently good. I believe that the deep roots of our theological heritage, the ancients who created this story and sent it on into the future, teach that violence and greed and suffering are the aberrations. Goodness is the existential default. Our world is drenched with it. Our challenge today is to live into this image of life, to build a faith in this vision of the world, to draw strength and resolve from it, and to make it so.

The first morning, whatever that means to you in your own life, dawns in beauty. “God saw that the light was good… and there was evening and there was morning, a first day.”

- Noah’s Ark - February 1, 2018

- On the First Day - September 1, 2016

- Sustainable Empathy - October 1, 2013

Quest Monthly Print Edition

Recent Issues

Latest Spiritual Reflection Posts

Weekly Newsletter

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210