REsources for Living

May 1, 2015Podcast: Download (5.4MB)

Subscribe: More

Contrary to popular belief, there is something to be said for failings and foibles. After all, mistakes are the basis of our whole diverse, ever-changing, interdependent web of life. Evolution only happens because of accidents and failures. Our genetic diversity starts with the fact that every now and again—pretty regularly, actually—something goes a bit wrong, and what we call a mutation takes place. A genetic mistake.

Contrary to popular belief, there is something to be said for failings and foibles. After all, mistakes are the basis of our whole diverse, ever-changing, interdependent web of life. Evolution only happens because of accidents and failures. Our genetic diversity starts with the fact that every now and again—pretty regularly, actually—something goes a bit wrong, and what we call a mutation takes place. A genetic mistake.

But sometimes those mistakes work out better than the “right” way, better than the perfect genetic copy. Those mistakes survive to be passed on in generations that are then labeled “successful.” Teachers tell us that evolution is about the survival of the fittest, but they can forget to mention that new versions of “the fittest” only happen through biological boo-boos.

Evolution aside, the world of science is littered with examples of mistakes that became monumental discoveries. Penicillin, for example, was discovered because a petri dish where bacteria was being cultured got contaminated with ugly, fuzzy green bread mold—a mistake a careful scientist should have been able to avoid. But instead, the Scottish scientist Alexander Fleming was able to remain creative and open-minded even in his accidents, and he realized that the area surrounding the mold was free of bacteria. Mold there, bacteria gone…something clicked.

Lots of painstaking and detailed research later, we have antibiotics—a major medical breakthrough of our scientific era, based on something that happened to go awry.

Mistakes are places where the unpredictable breaks through, where something utterly new and creative can spring up. Perhaps, in more theological language, mistakes and imperfections are the cracks in our solid selves where the divine can seep in. If, as I believe, God is a force of creativity at work in the world, then there would be no place for God if we were perfect, since perfection leaves no room for growth and change.

But our mistakes are only a blessing if we face them with an open mind and heart, with neither arrogance nor shame. And that, perhaps, is the real blessing of our imperfections: an opportunity for humility. Humility doesn’t play a very big role in our society. Generally what we see modeled today is either an arrogance that shirks responsibility and weasels out of admitting our failings, or the kind of arrogance that goes with self-abasement and self-flagellation, pretending that our own feelings of embarrassment and disappointment are more important than the effects our failings have on others.

Humility, being humble, is something different. To be humble is, quite literally, to take a step down, to move toward the earth. Indeed, the word “humble” has the same origin as the word “humus”—dirt. To greet our imperfections with humility is to get grounded, to get real with our limitations, so that we can deal with ourselves and the rest of the world as we really are, not as we would like to present ourselves.

That’s the thing about humility. It makes possible forgiveness. It’s terrifying to face people with your faults in full view, never knowing what they will see or how they will react. But it’s only when we stand before one another simply as who we are—warts, scabs, ugly bumps and all—that we create the possibility of being truly known. And it’s only when we create the possibility of being truly known that we create the possibility of being genuinely accepted.

When all that people can see of us is a glossy surface, then that is the only thing that can find a welcome in the world. But when we’re humble enough to let our imperfections show, we risk the possibility of finding what we most long for: the knowledge that we ourselves—in all our authenticity—are both acceptable and accepted by those who see us. From a place of humility we learn to take things as they are, rather than as they are ”supposed” to be, and to move forward from there.

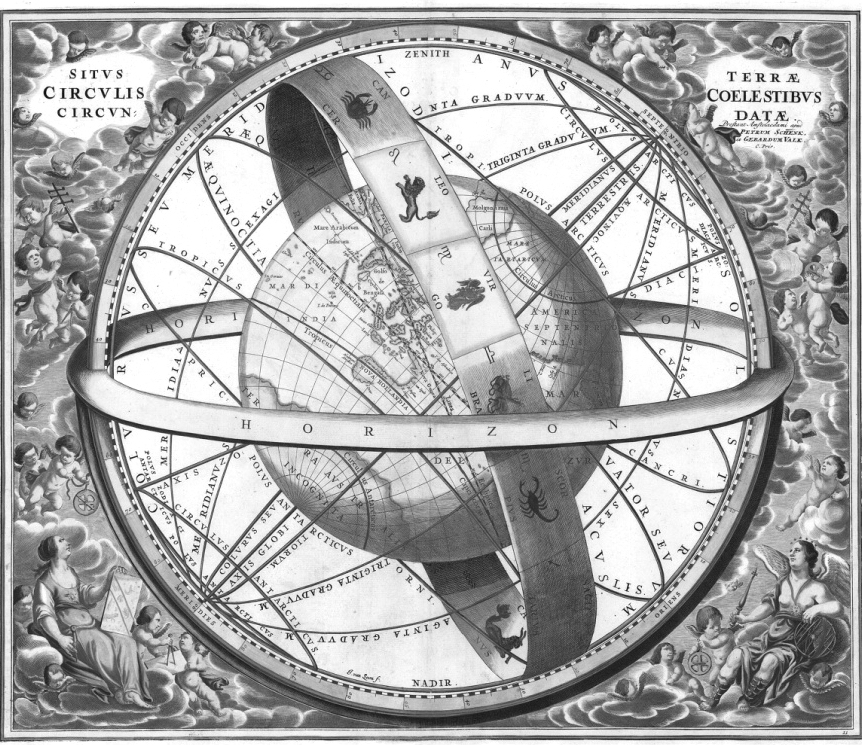

Perhaps it was a lack of humility that stumped early astronomers as they tried to chart the orbits of the planets. You see, in those days astronomy was very closely related to theology, since God was supposed to dwell out in the cosmos, reflected in the perfection of creation. The astronomers “logically” assumed, then, that since God was perfect, the planets must travel in perfect circles as they journeyed through space.

The problem, of course, is that planets don’t move in perfect circles. They move in ellipses—uneven, egg-shaped patterns that have to do with the laws of gravity rather than geometry. Clearly the theory was wrong. Just where the astronomers went wrong, however, is anybody’s guess. Perhaps they were arrogant in linking their science to the attributes of God. Perhaps there is no creator, or at least not one that actively choreographs the dance of planets through space.

Or perhaps the problem was as much one of bad theology as bad astronomy, and the Divine isn’t particularly interested in perfection, or in smooth, symmetrical, tidy spheres. Maybe the Holy rests not so much in the elegant dance of planets through space as it does in something much humbler, much closer to the earth, something imperfect and messy and real.

- REsources for Living - December 1, 2020

- A Fond Goodbye - December 1, 2020

- REsources for Living - November 1, 2020

Quest Monthly Print Edition

Recent Issues

Latest Spiritual Reflection Posts

Weekly Newsletter

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210