REsources for Living

May 1, 2019Podcast: Download (Duration: 5:35 — 5.2MB)

Subscribe: More

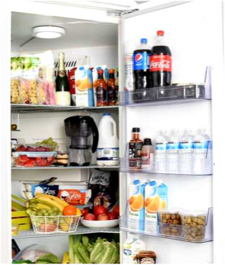

If, like me, you are fortunate enough to have a refrigerator and the means to fill it, it is possible that you have a tendency to stand in front of the open fridge, staring at the contents and wondering what there is to eat. It is even possible that some of us do this multiple times a day, staring at the shelves as if something would have magically appeared while the door was closed.

If, like me, you are fortunate enough to have a refrigerator and the means to fill it, it is possible that you have a tendency to stand in front of the open fridge, staring at the contents and wondering what there is to eat. It is even possible that some of us do this multiple times a day, staring at the shelves as if something would have magically appeared while the door was closed.

The thing is, when I stare at my open refrigerator—or at my open snack cupboard—it’s not just that I’m hungry. I’m hungry for something in particular, but I don’t know what. And so I stand there, wondering if what would satisfy me at this moment is avocado or cheese—or maybe both together on toast. What exactly is it that I want?

You could quite reasonably argue that my refrigerator-gazing habit is silly—I pretty much know what’s in there with the door closed, since I did the shopping and the cooking myself. And it is certainly not energy efficient to stand there letting the cold air out and the warm air in. But I would contend that the question that goes along with staring at the food is absolutely crucial.

What do I want? What exactly do I want? I imagine that pretty much all of us spend a lot of time dissatisfied with our own personal lives and with the world in general. We hunger for work that is meaningful and restorative rest and caring relationships and fun times and a world that is more just. And many of us have gotten pretty good at recognizing and sharing the many things we see that are wrong with the world—racism and homophobia and sexism and ableism and environmental degradation and corruption in government and the whole long list of very real, and often devastating, problems.

And it matters to identify those problems, whether personal or social. We need a clear analysis of what has gone wrong and why. But it seems to me that we often assume that identifying the problem is the same as finding a solution. Somehow we seem to think that if we tell our partner or our child how their looking at their phone during dinner makes us nuts, it should fix the relationship. Or maybe we figure that by sharing news of the latest police atrocity against a person of color on Facebook we are dismantling white supremacy.

And those are both perfectly good things to do. But they aren’t solutions. Solutions don’t start with what is wrong. Solutions start with the question What do I want? And the more precise we can be about what we want, the more specific we can be about how we might be able to get there.

What do I want from my family at dinner time? I want to hear about each person’s day, their successes and frustrations. I want to look in the eyes of the people I love. I want to share a story about something that happened to me today. I want to make plans for what we will do on the weekend. I want to hear about an idea you had or a book you read or something you learned.

When I know what I want, I can ask for it. I can make a plan for how I might get it. I shift the focus from how the other person is wrong to concrete steps that would move in the direction of something that is better. Of course, getting to those solutions is not necessarily easy. What I want may be in conflict with what someone else wants. Powerful forces may stand in the way of what I want. But creating change is only possible when you move step by step down the path of what exactly do I want?

To be clear, I’m not saying that there is some magic power that will manifest what you want if you just imagine it. I’m not a fan of the power of positive thinking, or of the prosperity gospel which seems to generate so much more prosperity for its preachers than for its followers.

The question What exactly do I want? is pragmatic, useful. What do I want? Justice. What exactly do I want? Well, it’s a long list, and I’m going to have to choose where I will focus my attention at any given point in time. I want an end to racist policing. OK, but that’s really what I don’t want. I don’t want racist policing. What do I want? I want police who understand their job as protecting and serving the entirety of the community where they work. I want police to choose de-escalation over force whenever possible. I want the police department to listen to the community about what would make people feel safer. I want police officers to be accountable for their behavior.

That list could go on and on, and each piece could be broken down into smaller pieces. But when I know what I want I can find other people who want the same thing, and we can find points in the system where we can exert pressure to accomplish those goals.

Maybe my standing in front of the refrigerator pondering what exactly I might be hungry for is a waste of time and energy. And it is possible to get what you wanted purely as a delightful surprise, without even knowing the hunger was there. But if you intend to actively pursue positive change, then the more exactly you know what you want, the better position you are in to make it happen.

- REsources for Living - December 1, 2020

- A Fond Goodbye - December 1, 2020

- REsources for Living - November 1, 2020

Quest Monthly Print Edition

Recent Issues

Latest Spiritual Reflection Posts

Weekly Newsletter

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210