Secret-Keeping

January 1, 2016Podcast: Download (Duration: 15:08 — 13.9MB)

Subscribe: More

I found out that something was wrong the same way I find out so many things nowadays: on Facebook. When I first joined that online social network, I was delighted to reconnect with friends from my growing-up years: high school buddies, former prom dates, even my best friend from Catholic elementary school, whom I hadn’t spoken to for 25 years. (She’s a stripper. I’m a minister. I’m not sure who was more surprised.)

I found out that something was wrong the same way I find out so many things nowadays: on Facebook. When I first joined that online social network, I was delighted to reconnect with friends from my growing-up years: high school buddies, former prom dates, even my best friend from Catholic elementary school, whom I hadn’t spoken to for 25 years. (She’s a stripper. I’m a minister. I’m not sure who was more surprised.)

Facebook also reconnected me with Anthony, the first boy I flipped head over heels for as a teenager. We grew up in the same college-and-cornfields town. Though our puppy love would wear off after a couple of years together, the tightly-knit web of small towns doesn’t always permit people to stray into different orbits. Such was the case with me and Anthony.

When I was in my 20s, Anthony and my parents bought houses across the street from one another. Whenever Mom and I chatted on the phone, she peppered our conversations with reports of her Anthony sightings: “I saw Anthony using his new lawn mower today.” Or “Anthony taught his daughter how to ride her bike this week.”

One summer, the reports turned grim: Anthony had testicular cancer, which soon spread to his brain. Over the next couple of years, he sought treatment at clinics across the country. He lost his hair to chemo. His workmates donated months of their vacation time so that Anthony wouldn’t lose his job. They held spaghetti dinners at the Elks Lodge, raising tens of thousands of dollars for his medical bills.

Then good news arrived through both Facebook and the small town grapevine: Anthony had returned to health and his job, and was fully living life.

Then….

I knew something was wrong when, one October day, I noticed a flurry of elegiac comments posted on his Facebook page. What was this? He had died? How? Not cancer, surely? What happened? I wrote to another childhood friend, a distant relative of Anthony’s, and learned only that Anthony had taken his own life. Beyond the sadness of his death, I was rattled by all that was left unspoken.

It took a full week for the breathtaking truth to emerge: Anthony never had cancer, at all. He’d been faking it all along, a fact that he confessed to his wife before killing himself, and which was confirmed in his autopsy.

“Anthony,” by the way, is not his real name. His story made a dramatic public splash in our hometown, but in this sermon I’m choosing to protect the privacy of his still-grieving family. You might say that his real name is my secret.

I’ll admit that this story is extreme; Anthony’s secret was of the highest order—concocted, spun and sustained by a troubled individual for reasons that no one will ever understand. His secret was powerful enough to manipulate a town full of caring people. Ultimately, it proved too powerful for Anthony to put back in the box. In the end, he must have been crazed with desperation, concluding that the only way he could escape his out-of-control secret—and sidestep the shame of revealing it—was by ending his life.

What secrets do any of us hold? Which of them have a hold over us? Which of our secrets are too big, or too painful, to keep? How do we discern whether or not to break secrecy—especially when the secret belongs to someone else? Does finding something out make it ours to know?

A minister’s job description is elastic. On any given day I’m called into service as a preacher, pastor, supervisor, facilitator, or counselor. When I sit with someone in crisis, a box of Kleenex between us, I sometimes remind people that one of my job descriptions is Keeper of Secrets. Actually, the clinical term would be Keeper of Confidentiality, not secrecy, since there are a few grave revelations that I’m not permitted by law or conscience to keep secret—elder abuse, for example, as well as physical or sexual abuse of a child, and the intent to harm self or others.

By and large, though, there’s a wide berth of clarity between those areas of mandated reporting and the confidences that I keep. And I do keep them, whether whispered through tears or offered up casually. I’ve been a minister for over a dozen years, and countless people have trusted me with their secrets: pieces of their life that they shelter in their souls, invisible from the rest of the world until they’re ready to be shared (or not).

Here’s what I’ve learned from the people I’ve served: holding on to secrets can require tremendous energy, and often imposes terrible loneliness on their keepers. But I’ve also learned that secret-keeping can sometimes incubate precious new growth within the soul. The bubble of privacy that a secret provides can create safe space for transformation—a motive that therapist David Richo calls “legitimate secrecy.”

The notion that secrets can be safe, albeit lonely territory is neither common nor popular. In fact, if you tuned into cultural messages, you’d think that all secrets are shameful or threatening. Here’s what I mean:

“Secrets are like vampires,” says author Jeannette Walls, “…they suck the life out of you.”

“Secrets are like stars,” counters Martha Beck. “They’re hot, volatile concentrations of energy.”

“The possession of secrets acts like a psychic poison,” writes Carl Jung.

And then there’s self-help guru Dr. Phil, who eschews poetic similes in favor of Texas straight-shootin’: “When we keep a secret…there is almost always shame involved. If the truth weren’t uncomfortable, why would anyone hide, enhance or completely alter it?”

Lots of reasons. There are lots of reasons, besides shame, that a person might hide the truth. For every “vampire” of a secret that swaddles danger, deception or deceit, there’s a secret that’s keeping someone safe or sane. For these reasons, I hold to what philosopher Sissela Bok labels “a neutral definition of secrecy.”

As Bok points out, secrecy—the act of concealing or hiding—is not quite the same beast as privacy (although they overlap) because “secrecy hides far more than what is private.

A private garden need not be a secret garden; a private life is rarely a secret life.” As she explains, secrets protect “the dangerous and the forbidden” as well as “the sacred, the intimate, the fragile.”

So much about our lives is fragile. We hold secrets about what we know and about what we’ve done (or not done). We also guard secrets about who we are. And, well, that’s where the sacred and the fragile meet. Not everyone is who they appear to be; not everyone can be who they appear to be. I’ve sat with people who wrestle with fundamental questions of identity, like sexual orientation and gender, as they try to find their authentic self. In such circumstances, secrecy can offer a bubble of safety, a cocoon in which the True Self can emerge.

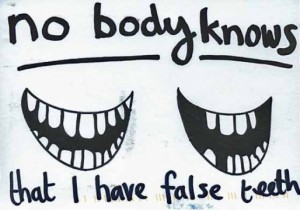

Here’s the thing, though: within that cocoon, the risk of keeping secrets about who we are is a splintering of the self. It can be exhausting. Anytime you keep a secret about who you are, you have to present to the world a substitute, inauthentic front that, unwittingly, snares other people into your false world. Keeping secrets about who we are involves manufacturing a false part of ourselves. Eventually, it can exact violence against the soul—or just outrun our energy to maintain it.

That’s why it’s so important to have people in our lives who are trustworthy enough to hold our secrets. And that’s why we need to be just as mindful and intentional about opening ourselves to receiving those secrets.

Some of us know that it can be far more difficult to be party to someone else’s secret than to own one ourselves. Being invited into secrets raises “questions of loyalty, conscience, and truthfulness,” says Sissela Bok, because learning others’ secrets can change us in ways we cannot control. “To acquire any new knowledge is to be changed… [and] the change, moreover, may be irreversible. One cannot unlearn a secret, no matter how unpalatable or dangerous it may be.” No wonder that some of us feel angry when we learn another person’s secret and are instructed not to tell.

What do we do when secrets—ours or others’—become too big to handle? When we can no longer hold onto different pieces of ourselves and preserve wholeness or integrity? What then?

The best I can do in the face of such questions is to offer these humble truths that I’ve salvaged, as bystander and secret-keeper, from the wreckage of Secrets Gone Wrong:

I believe that most people harbor secrets out of fear, and that at times the weight of a secret becomes its own punishment.

I believe that each of us has the right to say to a friend: “I care about you, but I don’t want to be put in the position of knowing your secret. Please don’t tell me any more.”

I believe that it’s more important to keep a secret uncomfortably than to seek relief by sharing it, if doing so will undo someone’s life.

I also believe that once someone shares a secret with us, that secret never stops belonging to the person who entrusted it to us. (Clearly, matters of mandated reporting are another matter.) Guardians of secrets don’t have the right to break secrecy without fully preparing the secret’s owner for that breach.

Underlying all of these convictions is a renewed appreciation for how complicated the world of secrets is, and how important it is to stir a generous dose of compassion into the mix of judgment and narrowed eyes. What if someone suffering under the fearsome weight of secrecy had even one compassionate listener to accompany them toward ease, toward truth, towards redemption?

I fell for Anthony, in a fit of puppy love, thirty years ago. I still think about him, and the wife and children who will never unravel the bitter mystery of his secret or the pain of his suicide. And I wonder: did he tell anyone? Did Anthony confide in his minister? In a therapist? Or did the weight of his secret break him because he was the only one carrying it?

Secrets can break people; they can also liberate people. In the words of Sissela Bok, “These conflicts are rooted in the most basic experience of what it means to live as one human being among others.”

May we each embrace this life, as one human being among others, calling forth compassion as we discern our way out of brokenness into the ways we become whole.

- Secret-Keeping - January 1, 2016

- The End Is Not Near - April 1, 2014

- The Impossible and the Laughable - April 1, 2011

Quest Monthly Print Edition

Recent Issues

Latest Spiritual Reflection Posts

Weekly Newsletter

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210