The Language of Faith

November 1, 2013

Source: Google Images Creative Commons

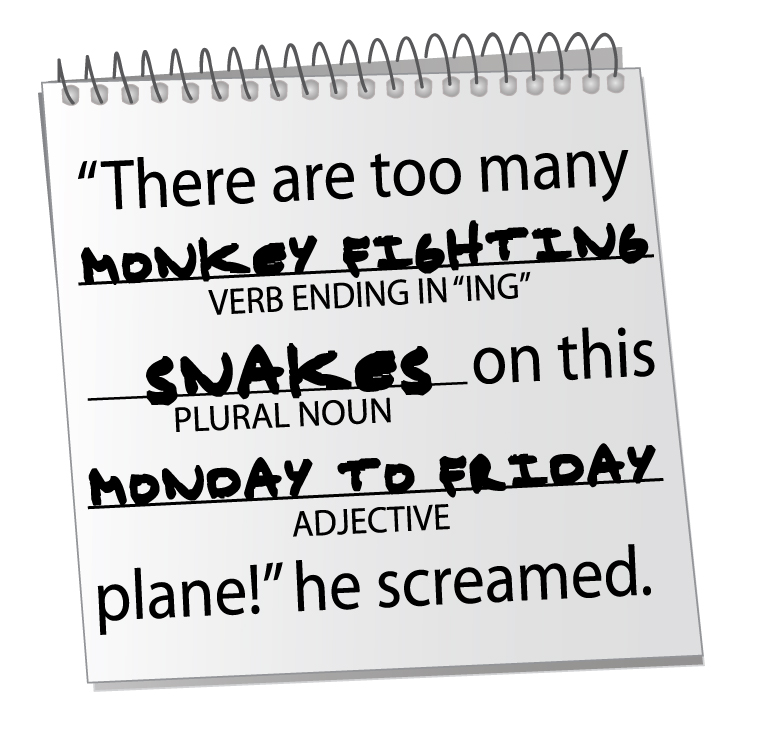

Last Sunday, while out to lunch with my husband and two young kids, we passed the time waiting for our food by playing Mad Libs. As you might remember, Mad Libs is a word game where one player asks another player to provide a particular kind of word – noun, verb, adjective, etc. – to fill in the blanks of a story. After the words are provided, randomly and without context, the other player reads the funny and often nonsensical story aloud.

If you have ever played Mad Libs, you know just how important grammar and semantics are to the art of storytelling. You also realize just how important words and context are to communication and understanding.

Words are, obviously, incredibly powerful tools. We use words to communicate, to connect, to explain, to inform, and to educate. But words have significant limitations, as well. Unfortunately, all too often words are used as a weapon instead of a tool. We use words to restrict instead of expand, to assume instead of discover.

Ironically, we often try to use language to define those things that are undefinable. We try to explain the inexplicable with rational, but overly simplistic, definitions. We fit people into our prepackaged labels –believer, nonbeliever, Christian, Jew, Muslim, atheist, humanist, idealist, pacifist, liberal, or conservative – and we try to make sense of this crazy, nonsensical, Mad Libs-like world with assumptions and categories.

But when it comes to the Big Questions, to matters of the Heart and the Spirit, there are no definitions. There are no labels. There are no prepackaged boxes.

Quite simply, language fails us when it comes to matters of the Spirit. God (I use the word “God” knowing that the word itself has its own limitations) comes in many names and is experienced in many ways. God and all things Spiritual, by their very nature, are unknowable and personal; they are felt with the heart and cannot always be adequately explained with words.

But, being the intelligent humans that we are, we try to explain that which is deeply felt with words, explanations, and sound bites. And, as a result, any inherent commonality to our human spirit gets lost, the beautiful complexity of differences gets diluted. The words – and labels – that we use become more important than the ideas.

So much division and dissention is created and exacerbated by the labels and linguistic limitations that we put on matters of faith and spiritual belief – concepts that are, quite frankly, too big to fit into any label or verbal representation.

Perhaps, we need to focus less on the words of faith and more on the language of faith. Perhaps we need to stop getting lost in the semantics of God and, instead, learn the languages of God – ones that are spoken and heard in a number of ways.

Music has always been my language of God. I love to sing (off-key) and can clumsily tap away a few songs on the piano, but I am far from what you would call “musical.” Yet music has always been a profoundly moving spiritual experience for me. Whether I’m swaying to a church choir singing “Amazing Grace,” listening to Bon Iver on my iPod, singing along to Bob Dylan in the car, or dancing like crazy with my kids in the kitchen, few things have the power to move me like music. Music creates an internal communication with the Spirit that washes my soul clean, as if I have stepped into a warm shower with the lyrics and melody rinsing away the grit and grime of everyday life.

Spiritual language can be found in any number of ways. My grandpa spoke the language of God through his generous hospitality. It was nearly impossible not to feel like THE most important person in the world when he greeted you. Others feel the language of God through the earth and nature. Gardening, for my paternal grandma, was so much more than a household chore, it was a spiritual practice unto itself. With her fingernails soiled and her hands calloused, as she tended and cultivated, she spoke a spiritual language that only her soul understood, that only her Spirit could appreciate.

Some people speak God’s language through art or poetry, photography or painting, teaching children or caring for animals, caring for the sick or sharing a meal with friends. Shauna Neiquist wrote in Bread and Wine, “When the table is full, heavy with platters, wine glasses scattered, napkins twisted and crumpled, folks askew, dessert plates scattered with crumbs and icing, candles burning low – it’s in those moments that I feel a deep sense of God’s presence and happiness. I feel honored to create a place around my table, a place for laughing and crying, for being seen and heard, for telling stories and creating memories.”

Let’s face it, we live in a chaotic world, where the unimaginable meets the incomprehensive, and devastating realities mix with everyday miracles. We want to make sense of it all. Of course, we do. In our well-intentioned, but misguided, attempts to explain, understand, and communicate, we look to definitions and labels. We rely on assumptions and suppositions, and we look to linguistic placeholders to meet the expansive scope of faith, God, and the Spirit.

We try to define the indefinable.

But maybe if we spend a little less time focusing on definitions of God and labels of faith, and instead focused on feeling the complex languages of God, maybe then we could gain a better understanding of each other and ourselves.

- Too Much Noise - May 2, 2014

- Simple Prayer, Profound Meditation - April 18, 2014

- When Plans Go Awry - March 7, 2014

This content is cross-posted on the UU Collective, a Patheos blog.

Renew Your Membership

We invite you to join your fellow CLFers to renew your CLF membership and stewardship of the CLF for another year.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210