What Justice Looks Like

May 2, 2016Sometimes, it is tempting to think about justice only as something “out there,” something that is about causes and actions and social change. But justice is also about how we treat ourselves and the people around us and in our families. The way we treat people individually has a big impact on those larger issues, even if it’s hard to tell right away.

Dr. Cornel West tells us, “Justice is what love looks like in public.” You can tell yourself this quote too, to remind you of why justice is so important. When we work for justice, we are embodying love in our communities; this is how we change the world!

Making Justice Now

May 2, 2016Usually we honor someone from our history who serves as a role model on this page, but there are plenty of UU justice-makers who are living and working right now.

Take, for instance, Lena K. Gardner, who is the Membership and Fundraising Director for our own Church of the Larger Fellowship. Lena is a leader with the Black Lives Matter movement in Minneapolis, Minnesota. She organizes and speaks out and brings people together to protest racist ways that the police have treated Black people in their community and other places around the country.

Working with many other people—many of them young adults or even teenagers, they have protested police killing unarmed Black people and demanded that city officials change policies to hold police accountable.

Always using peaceful strategies, they have held protests in America’s biggest shopping mall and on the highway and in front of a police station.

Some people have objected to the Black Lives Matter slogan, saying that all lives matter. But Lena and many others are pushing people to understand the many ways in which Black people are treated as if their lives don’t matter. They are working for a world where everyone finds fairness.

Moving Toward Freedom

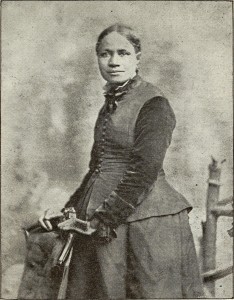

March 31, 2016Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was born a free Black woman in Baltimore, Maryland in 1825. She was raised in the household of her uncle, an educator and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) minister. He was also an abolitionist—a person who objected to the enslavement of blacks. Harper became an educator and abolitionist as well. She also became a writer, publishing her first book of poetry at twenty and later in life publishing the first short story by an African American woman. Her writing often urged Blacks, women, and people in oppressed groups to take a firm stand for equality and freedom.

In 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was passed. It became dangerous to be a free Black in Maryland because slave owners could claim Black people were runaway slaves and force them into slavery. So, Harper moved farther north to Ohio and then to Philadelphia. She taught, ran part of the Underground Railroad helping slaves escape to freedom, and lectured around the country.

In 1863, abolitionists celebrated success with the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the slaves. But there was a long road ahead to full equality, and Harper spent the rest of her life working for women as well as African Americans to have access to full freedom and justice.

To read some of Harper’s poems click here.

Beautiful and Broken

March 1, 2016A mosaic is a kind of artwork that is made by creating a picture out of pieces of pottery. It’s a way that something broken can turn into something beautiful.

One way to play with the idea of a mosaic is to draw an abstract picture, full of color and shapes, but not necessarily of a particular thing like a cat or a robot. Then cut the picture up. Break it on purpose. Then glue the pieces onto a piece of construction paper, leaving just a little gap between each piece.

You will create a new, and maybe surprising, piece of art by taking the original drawing apart and putting it back together in a different form.

Whole, Not Broken

March 1, 2016Christopher Reeve had everything going for him. He was handsome and athletic and famous for playing Superman in the movies. He had a lovely family and plenty of money that he’d made as a movie star. Really, things could hardly have been better.

Until he was in a horse bock riding accident that damaged his spine and left him paralyzed below his neck. He couldn’t move his hands or feet, let alone play a superhero who could jump tall buildings in a single bound. He was, in a profound way, broken.

But in many other ways, he was deeply whole. He had a family who loved him and believed in him. And he found in his Unitarian Universalism a reminder that one way we can build wholeness for ourselves is by doing what we can to build wholeness for others.

So Christopher and his wife Dana dedicated themselves to trying to make life better for other people who had spinal cord injuries. They raised money to help people get things they needed like ramps and vans that could carry wheelchairs. And they raised money for research that might help people with spinal cord injuries.

Christopher Reeve eventually died from the complications of living with his injury, but his living taught a lot of people about what can be whole when things get broken.

Renew Your Membership

We invite you to join your fellow CLFers to renew your CLF membership and stewardship of the CLF for another year.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210