Moving Toward Freedom

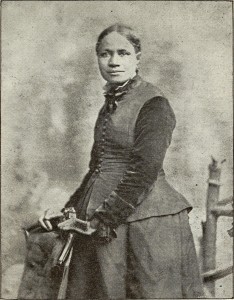

March 31, 2016Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was born a free Black woman in Baltimore, Maryland in 1825. She was raised in the household of her uncle, an educator and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) minister. He was also an abolitionist—a person who objected to the enslavement of blacks. Harper became an educator and abolitionist as well. She also became a writer, publishing her first book of poetry at twenty and later in life publishing the first short story by an African American woman. Her writing often urged Blacks, women, and people in oppressed groups to take a firm stand for equality and freedom.

In 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was passed. It became dangerous to be a free Black in Maryland because slave owners could claim Black people were runaway slaves and force them into slavery. So, Harper moved farther north to Ohio and then to Philadelphia. She taught, ran part of the Underground Railroad helping slaves escape to freedom, and lectured around the country.

In 1863, abolitionists celebrated success with the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the slaves. But there was a long road ahead to full equality, and Harper spent the rest of her life working for women as well as African Americans to have access to full freedom and justice.

To read some of Harper’s poems click here.

Whole, Not Broken

March 1, 2016Christopher Reeve had everything going for him. He was handsome and athletic and famous for playing Superman in the movies. He had a lovely family and plenty of money that he’d made as a movie star. Really, things could hardly have been better.

Until he was in a horse bock riding accident that damaged his spine and left him paralyzed below his neck. He couldn’t move his hands or feet, let alone play a superhero who could jump tall buildings in a single bound. He was, in a profound way, broken.

But in many other ways, he was deeply whole. He had a family who loved him and believed in him. And he found in his Unitarian Universalism a reminder that one way we can build wholeness for ourselves is by doing what we can to build wholeness for others.

So Christopher and his wife Dana dedicated themselves to trying to make life better for other people who had spinal cord injuries. They raised money to help people get things they needed like ramps and vans that could carry wheelchairs. And they raised money for research that might help people with spinal cord injuries.

Christopher Reeve eventually died from the complications of living with his injury, but his living taught a lot of people about what can be whole when things get broken.

Wishing for Something New

January 1, 2016Many people make resolutions for the New Year of things that they plan to do differently. And many people break those resolutions before the week is out because they didn’t really want to make those changes to begin with. So it helps to start with a resolution that you DO want, not that you think you SHOULD want.

What is one thing that you really, really hope is part of your year to come? Write it down and put it in a jacket pocket. Now you have the year to figure out how to make your wish come true.

An Unexpected Second Chance

January 1, 2016John Murray was a Universalist who certainly took starting fresh to heart. Tragedy struck for Murray when his wife and young son died, and then he was put in jail because he was unable to pay his bills.

In 1770 he felt able to make a totally fresh start, so he got on a ship and headed for the New World, North America. Unfortunately, the ship got stuck just off the shore of New Jersey, when they were trying to get to New York.

But Murray agreed to go on shore and try to find directions and supplies. He ended up on the doorstep of a man named Thomas Potter, who greeted him as the Universalist preacher that Potter had been waiting for!

Well, Murray didn’t have plans to be a Universalist preacher—that wasn’t the fresh start he had in mind. He wanted to go on to New York. But he agreed that if they didn’t get the wind the boat needed to sail on, that he would preach on Sunday about Universalism’s message of an absolutely loving God.

Well the wind didn’t pick up, and Murray did preach, and he ended up making a fresh start by marrying Potter’s daughter and becoming a traveling preacher, spreading the good news of God’s love all over New England.

Hopes for the Day

December 1, 2015Setting intentions is a way of practicing mindfulness by focusing on the kind of day, week, year or life you’d like to have, and visualizing the actions you can take to achieve your hopes. It’s a practice that can work for adults, teens and children alike.

If you have time as a family to gather in the morning, take turns sharing your intentions for the day. You could even light a candle or write down your intentions together on a chalkboard or paper, or construct a family ritual of your own. (If time in the morning is stretched thin, you could also take time during the evening or bedtime the night before.)

Children will likely need some help learning this new practice. A good question to begin with is, “What good do you want to invite into your life today?” You can suggest some general feelings that a child might understand and hope to experience: love, peace, joy, fun, safety and success are all good starters.

Brainstorm with children to come up with concrete ways they could experience these feelings during the day, such as “I want to invite success into my life by acing my math test,” or “I want to experience fun by playing with my friends at recess, or “I want to invite peace into my world by talking to kids at school that look lonely.” Yoga Chicago offers some other great suggestions for setting intentions with children that apply well for all ages.

Lastly, visualize these things happening: sitting down to take the math test and knowing all the answers, being a good friend to classmates so that you can enjoy fun together at recess, being mindful of which classmates could use a friendly ear, and striking up conversation. (Visualizing your hopes for the day is also a great meditative exercise for adults, too!)

For additional ideas for setting intentions for yourself or for your family, visit Playful Planet’s website.

On Setting Out and Coming Home

November 1, 2015Podcast: Download (Duration: 11:02 — 25.3MB)

Subscribe: More

Matsuo Bashō, the late 17th century Japanese poet, speaks of a strong desire to wander, as if it’s the essence of who he is. In the opening lines of his travel sketch, The Narrow Road to the Deep North, he says: “The gods seemed to have possessed my soul and turned it inside out, and roadside images seemed to invite me from every corner, so that it was impossible for me to stay idle at home.” Read more →

CLF Nominating Committee Seeks Leaders

November 1, 2015Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:24 — 1.3MB)

Subscribe: More

The Church of the Larger Fellowship’s Nominating Committee seeks CLF members to run for positions on the Board of Directors beginning June 2016: Read more →

Trail Blazers and Covenant Keepers

November 1, 2015Podcast: Download (Duration: 9:54 — 9.1MB)

Subscribe: More

As a little girl I ran away from home at least twice every summer, hurling myself out of the house with outrage at childhood oppressions like being left out by my brother and his friends or facing bad sportsmanship during a T-ball game. Read more →

Opportunities to Journey

November 1, 2015Podcast: Download (Duration: 0:53 — 833.6KB)

Subscribe: More

“The only journey is the one within.” —Rainer Maria Rilke Read more →

Renew Your Membership

We invite you to join your fellow CLFers to renew your CLF membership and stewardship of the CLF for another year.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210