Did You Know?

December 1, 2016Podcast: Download (Duration: 0:16 — 266.1KB)

Subscribe: More

…that the CLF is hoping to send holiday cards to our more than 700 prisoner members? You can help. Read more →

Another Kind of Knowledge

December 1, 2016Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:09 — 1.1MB)

Subscribe: More

Prepare the way to welcome your inner Christ child—the being of love and light, the spark of holiness that lies deep in us all. Read more →

Prepare the way to welcome your inner Christ child—the being of love and light, the spark of holiness that lies deep in us all. Read more →

Ways to Wait

November 30, 2016It’s easy to get impatient when waiting for something exciting. Whether it’s waiting just a few minutes for school to end, waiting till dinner for your favorite meal, or waiting several days, weeks or even months for a special event, trip or holiday, it can be hard not to get impatient. (“Only 287 days till my birthday!” Sound familiar?)

When we’re impatient, our bodies and feelings might give us some clues. Some people notice they are breathing faster. Maybe you find your hands are balled up into fists, or you are using your pen to drum on the table. Maybe you can’t stop bouncing up and down on the balls of your feet or walking around the room. You might feel like you are in a big hurry, or get nervous.

These are all normal when we are waiting for something exciting or important, and sometimes waiting can be fun. But sometimes, we also wait for hard things, like news from a doctor or veterinarian about a loved one or pet who’s sick. And sometimes, we want to just relax!

Patience is kind of like a muscle, and we have to exercise it in order for waiting to be something we are good at doing. If you are feeling anxious about waiting or impatient, or if you want to practice for the next time you need to wait for something, here are eight tools you can practice and take with you for when waiting gets difficult.

-

Look up at the sky and imagine shapes in the clouds.

-

Smile at a friend or family member, or go and talk to them while you wait.

-

Count the number of freckles on your arm, leaves on the ground, change in your pocket . . . count whatever you like! It keeps your mind busy. You could also name (out loud or in your head) as many details of what you see in front of you, or the names of all the United States presidents that you know. What’s important is that you are giving your brain something different to think about.

-

Sing a song (out loud or in your head)

-

Making up a story, either by yourself or with friends.

-

Take ten slow easy breaths. For every breath, think of something you are grateful for.

-

Remember a favorite memory, and try to picture it in your head like a snapshot. What are all the details of the image?

-

Remember your five senses. What can you see and hear? Where are you standing or sitting? Feel the seat or ground below you, or touch what’s nearby is (if it’s safe to do so). Take a deep breath and stick out your tongue. Are there any smells or tastes where you are?

(These suggestions, adapted from A Fine Parent blog, are useful for folks of all ages who’d like to exercise their patience muscles. )

Meditation is another tool that can help us handle those in-between times when waiting is hard. And children as well as adults can benefit from this practice. Through meditation, kids as well as adults can better focus and be present in their lives, which can sometimes make waiting easier.

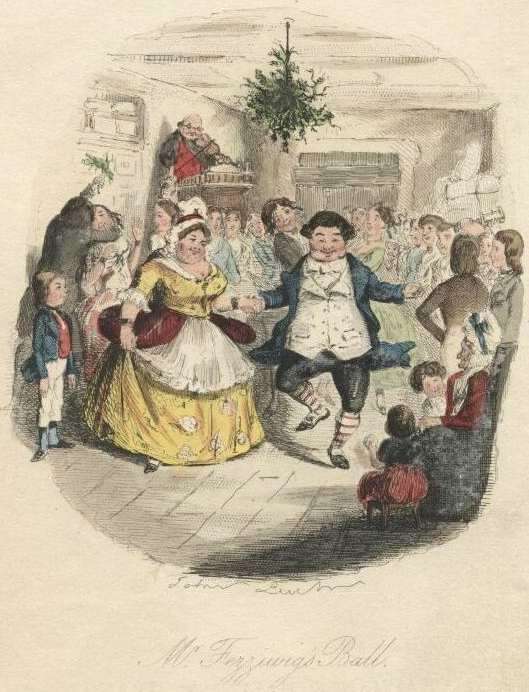

The Father of Christmas

November 30, 2016This month we celebrate Charles Dickens, British Unitarian, and author of A Christmas Carol. When Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol in 1843, many Christmas traditions had almost died out, and the holiday was hardly celebrated. England was becoming more and more industrial, and people leaving farms to work in factories had left their old customs behind.

But the story, which was wildly popular, brought enthusiasm back to the cities for practices like singing Christmas carols and feasting on special foods. The picture of the Cratchit family celebrating their Christmas together inspired people to find a way to celebrate Christmas in the cities, and the change of heart which comes to Ebeneezer Scrooge reminded people that Christmas was traditionally a time when the wealthy folk shared with the poorer people.

In fact, Dickens was very concerned with the conditions of poor people in England at a time when the gap between the rich and the poor was getting wider and wider. Many of his books deal with this theme, and he became a Unitarian because, as he said, they “would do something for human improvement if they could; and practice charity and toleration.”

Interested in learning more about Charles Dickens, our religious ancestor? Here are a few additional resources:

A 2005 UU World article, “Ebenezer Scrooge’s Conversion,” by Michael Timko, describes how Charles Dickens’s story, A Christmas Carol, exemplified 19th-century Unitarianism.

In the Tapestry of Faith children’s religious education curriculum Windows and Mirrors, Session 13 (Images of Injustice) addresses Charles Dickens, his work and his dedication to improving the lives of the poorest English workers and their families. From the introduction to the lesson:

As Unitarian Universalists, we do not turn away from noticing the gaps that separate “haves” from “have nots.” To work against inequity, we know we first have to see it. Unitarian Charles Dickens saw it. Born poor, he later earned a living as a writer and joined a more comfortable economic class. Dickens used colorful character portraits and complex, often humorous plots, to expose tragic inequities in 19th-century British society. He showed that people at opposite ends of an economic spectrum belong to the same “we,” united by our common humanity and destiny—a lesson which resounds with our contemporary Unitarian Universalist Principles.

The website Charles Dickens online has well as the Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography offer biographical information and many other resources.

More than Words

November 8, 2016A lot of times, prayer can seem like something that is done with words and thoughts rather than action. For people who like to use their hands or bodies, it can sometimes be hard to connect to the idea of prayer, and this is doubly true when we are praying with or as children. But around the world, in many cultures and faith, there are prayers that are made with our bodies, with movement or by creating something with our hands. Read more →

Choosing When to Pray

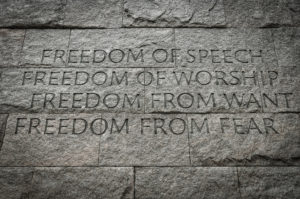

November 1, 2016Prayer is an important part of the spiritual lives of many UUs—but we also are clear that people need to choose for themselves how and when they will pray. It isn’t the government’s place to decide that for people.

In the early 1960s the UU Schempp family helped to make that clear in American law. Sixteen-year-old Ellery Schempp wasn’t comfortable with having to say the Lord’s Prayer and listen to Bible readings at his public school. His parents, Ed and Sidney Schempp, talked about the issue with Ellery and his siblings Roger and Donna. Together they decided that not only was it not right for Ellery to have to say a prayer he didn’t believe in, no kid should be required to say a prayer that didn’t match their beliefs or faith tradition.

So the Schempps challenged the school in court, and their case went to the Supreme Court. In 1963 the court ruled in Abington Township School District v. Schempp that it was unconstitutional for a public school to expect students to participate in school-sponsored religious activity. The 1st Amendment of the US Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, and a UU family stood up to make sure that children were included in that guarantee.

Meal Blessing

November 1, 2016Here is a little prayer of thanksgiving that your family might want to sing at meal times.

Thank you for this food, this food,

this glorious, glorious food,

and the animals, and the vegetables,

and the minerals that made it possible.

A Thousand Ways to Pray

November 1, 2016Podcast: Download (Duration: 9:42 — 7.8MB)

Subscribe: More

Early in my ministry career I interned as a religious studies teacher at Milton Academy, a prep school in New England. Read more →

Early in my ministry career I interned as a religious studies teacher at Milton Academy, a prep school in New England. Read more →

The Call to Prayer

November 1, 2016Podcast: Download (Duration: 12:26 — 7.7MB)

Subscribe: More

Allahu Akbar, the voice calls four times: “God is the most great.” Read more →

Allahu Akbar, the voice calls four times: “God is the most great.” Read more →

Love Larger

We rely heavily on donations to help steward the CLF, this support allows us to provide a spiritual home for folks that need it. We invite you to support the CLF mission, helping us center love in all that we do.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Latest Spiritual Reflection Posts

Latest Quest Monthlies

Weekly newsletter

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.