The Language of Faith

November 1, 2013

Source: Google Images Creative Commons

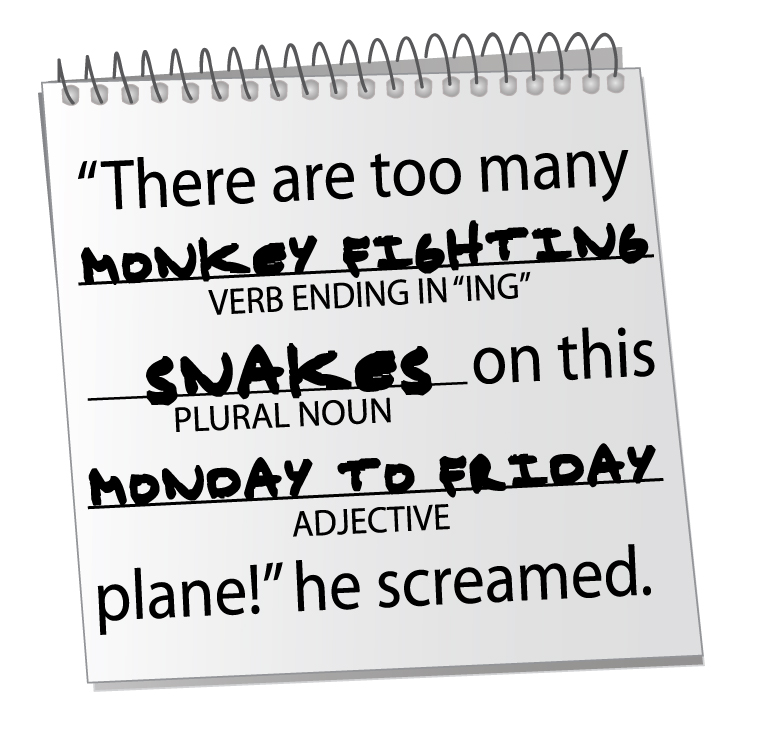

Last Sunday, while out to lunch with my husband and two young kids, we passed the time waiting for our food by playing Mad Libs. As you might remember, Mad Libs is a word game where one player asks another player to provide a particular kind of word – noun, verb, adjective, etc. – to fill in the blanks of a story. After the words are provided, randomly and without context, the other player reads the funny and often nonsensical story aloud.

If you have ever played Mad Libs, you know just how important grammar and semantics are to the art of storytelling. You also realize just how important words and context are to communication and understanding.

Words are, obviously, incredibly powerful tools. We use words to communicate, to connect, to explain, to inform, and to educate. But words have significant limitations, as well. Unfortunately, all too often words are used as a weapon instead of a tool. We use words to restrict instead of expand, to assume instead of discover.

Ironically, we often try to use language to define those things that are undefinable. We try to explain the inexplicable with rational, but overly simplistic, definitions. We fit people into our prepackaged labels –believer, nonbeliever, Christian, Jew, Muslim, atheist, humanist, idealist, pacifist, liberal, or conservative – and we try to make sense of this crazy, nonsensical, Mad Libs-like world with assumptions and categories.

But when it comes to the Big Questions, to matters of the Heart and the Spirit, there are no definitions. There are no labels. There are no prepackaged boxes.

Quite simply, language fails us when it comes to matters of the Spirit. God (I use the word “God” knowing that the word itself has its own limitations) comes in many names and is experienced in many ways. God and all things Spiritual, by their very nature, are unknowable and personal; they are felt with the heart and cannot always be adequately explained with words.

But, being the intelligent humans that we are, we try to explain that which is deeply felt with words, explanations, and sound bites. And, as a result, any inherent commonality to our human spirit gets lost, the beautiful complexity of differences gets diluted. The words – and labels – that we use become more important than the ideas.

So much division and dissention is created and exacerbated by the labels and linguistic limitations that we put on matters of faith and spiritual belief – concepts that are, quite frankly, too big to fit into any label or verbal representation.

Perhaps, we need to focus less on the words of faith and more on the language of faith. Perhaps we need to stop getting lost in the semantics of God and, instead, learn the languages of God – ones that are spoken and heard in a number of ways.

Music has always been my language of God. I love to sing (off-key) and can clumsily tap away a few songs on the piano, but I am far from what you would call “musical.” Yet music has always been a profoundly moving spiritual experience for me. Whether I’m swaying to a church choir singing “Amazing Grace,” listening to Bon Iver on my iPod, singing along to Bob Dylan in the car, or dancing like crazy with my kids in the kitchen, few things have the power to move me like music. Music creates an internal communication with the Spirit that washes my soul clean, as if I have stepped into a warm shower with the lyrics and melody rinsing away the grit and grime of everyday life.

Spiritual language can be found in any number of ways. My grandpa spoke the language of God through his generous hospitality. It was nearly impossible not to feel like THE most important person in the world when he greeted you. Others feel the language of God through the earth and nature. Gardening, for my paternal grandma, was so much more than a household chore, it was a spiritual practice unto itself. With her fingernails soiled and her hands calloused, as she tended and cultivated, she spoke a spiritual language that only her soul understood, that only her Spirit could appreciate.

Some people speak God’s language through art or poetry, photography or painting, teaching children or caring for animals, caring for the sick or sharing a meal with friends. Shauna Neiquist wrote in Bread and Wine, “When the table is full, heavy with platters, wine glasses scattered, napkins twisted and crumpled, folks askew, dessert plates scattered with crumbs and icing, candles burning low – it’s in those moments that I feel a deep sense of God’s presence and happiness. I feel honored to create a place around my table, a place for laughing and crying, for being seen and heard, for telling stories and creating memories.”

Let’s face it, we live in a chaotic world, where the unimaginable meets the incomprehensive, and devastating realities mix with everyday miracles. We want to make sense of it all. Of course, we do. In our well-intentioned, but misguided, attempts to explain, understand, and communicate, we look to definitions and labels. We rely on assumptions and suppositions, and we look to linguistic placeholders to meet the expansive scope of faith, God, and the Spirit.

We try to define the indefinable.

But maybe if we spend a little less time focusing on definitions of God and labels of faith, and instead focused on feeling the complex languages of God, maybe then we could gain a better understanding of each other and ourselves.

In The Waiting Time

October 28, 2013I really do not like waiting. I will put something back on a shelf rather than wait in a long check-out line. I will shop online, choose a different restaurant, come back later, or change my plans altogether to avoid a line.

I hate waiting for a bus too. Why stand and wait when I can start walking now? Usually, the bus passes me as I am chugging along down the street. It does not phase me. At least I didn’t wait, I tell myself. A funny logic, I know.

I remember as a child waiting for special days, like birthdays and Christmas, and feeling as though time was moving as slow as molasses. As a teenager, I would count down days until I could visit out-of-town friends or go to summer camp: month after next, week after next, day after the day after tomorrow. It felt like time crawled until finally it was … today! And somehow, the long-awaited day had arrived.

I am waiting now like I have never waited in my life. Expecting the child that I have carried for the past nine months to come into the world, I cannot make this magical event happen on my timeline. I cannot just set off walking. I cannot make a different choice or come back later.

I am waiting now like I have never waited in my life. Expecting the child that I have carried for the past nine months to come into the world, I cannot make this magical event happen on my timeline. I cannot just set off walking. I cannot make a different choice or come back later.

My spouse and I have waited, counting months and weeks and days, watching my body change, following our baby’s development step by step: organs and fingernails and eyelashes. We have moved from flutters to kicks to rolls, reveling in bulges that are feet and elbows, imagining what they might look like on the outside.

The leaves are changing here in New England and falling, one by one, covering the ground, shuffling under my feet as I walk, slowly now, talking to the baby: We are ready for you. Come ahead. The days grow shorter and the ground grows colder, prepping for dormancy, for a winter of waiting. Our waiting time is now. We wait for life to emerge.

Enjoy the wait, they say. While it’s still just the two of you. While you and baby are one. Pregnancy is to be savored, they say. Well, mine has been complicated, often hard to savor, and at this point I am rather uncomfortable. But there is wisdom in their words.

And so I am practicing something that does not come naturally: enjoying the wait. I am practicing savoring each day, each moment that my babe and I are joined in this most intimate way that will never be again. I am practicing breathing deeply, being present, watching the leaves fall, waiting for our lives to change irrevocably, for our hearts to be transformed in ways we cannot imagine. Waiting becomes the practice itself.

We are over a month from the beginning of Advent, yet I have never understood the season as well as I do now: patience and reflection. Calmly, quietly preparing body, heart, and soul for the miracle that will be.

Relationship First

March 12, 2013“If words come out of the heart, they will enter the heart, but if they come from the tongue, they will not pass beyond the ears.” Al-Suhra Wardi , Persia, 12th Century

This morning I listened to the Diane Rehm show on my local NPR station; she interviewed Deborah Hicks who has written a book about her work teaching poor Appalachian girls. Toward the end of the show, Diane asked Dr. Hicks what were the lessons of her work. (http://thedianerehmshow.org/shows/2013-03-12/deborah-hicks-road-out-teachers-odyssey-poor-america) The first lesson, the author replied, was that relationships come first. She needed to listen to her students and to learn who they were and what was important to them before she could really teach them.

Her simple reply led me into thought. We so often forget that it is always relationships first. We become who we are only through relationships. With healthy authentic relationships, we can grow and flourish. With healthy relationships, we can both laugh and cry; we can both work and play. With honest listening relationships, we can both agree and disagree.

Without authentic relationships, we develop an edge. We may shrivel up, and we are more likely to be afraid or angry. Too often, we let fear or judgment interfere with our relationships and prevent us from living and loving fully. We can let unhealthy relationships damage us; suspicious and angry relationships cause us to doubt ourselves and lose our vitality.

My young adult daughter is recently divorced and in a new relationship. Her new relationship seems to be firmly grounded in honesty, trust and fun. She reported to us that her co-worker and friend of four years told her that she was the happiest that he had ever seen her. I reflected that indeed she is happier than she has been in these last few years. For several years, even when she was happy, she had a tense edge. Now, that edge is gone; she is relaxed and happy. In her marriage, she had been hurt and she was fearful. Her husband blamed her for all problems and liked to tell her what was wrong with her. Her new partner listens to her, shares what he is thinking and feeling, and likes her. They are having fun together.

As it is with teachers and students and in close personal relationships, so it is with congregations. Clergy and congregations can grow and flourish together when we remember that it is always relationships first. It can be hard to enter openly into new trusting relationships. It requires that one likes and trusts oneself enough to truly listen to the other and learn who they are. When clergy enter a new community determined that it y should be the kind of congregation that they want it to be, they are not fully open to authentic relationship. When congregants have decided who the new clergy person is before establishing a relationship, they are also not open to authentic relationship. Communities and clergy may survive but they will not flourish without authentic relationship, without trust.

It is not always easy to enter into new relationships with authenticity and trust. Sometimes when I speak the words from my heart, they come with tears. It is not always easy, but it is always relationships first.

May your words come from your heart and be received by open hearts.

Faith to Live, Faith to Die

January 27, 2013I spent yesterday with an almost 90 year old woman I’ve loved for decades, just home from the hospital following congestive heart failure.

A cracker jack team of doctors, as well as a bevy of loving friends and family members, have surrounded her all week, attempting to figure out exactly what is causing her heart to weaken and not pump efficiently. They’re talking about medicine and diet and possible surgery.

She’s clear, herself, about what’s going on: “I’m old,” she says calmly. “My heart is old.” She seems completely at peace with what will happen next, be it more tests and fussing, be it, ultimately, drawing her last breath on this planet sooner rather than later. I can see from her strength that she won’t do anything she doesn’t want to do, but she isn’t troubled by what other people need to do around her either.

Her devout Catholic faith brings her great comfort now, as it has every day of her life.

The priest has been to see her at her hospital bedside, performed what she says is no longer called last rites but “prayer for the sick” and told her, “Your sins are all forgiven now, so don’t mess it up!” She twinkles when she repeats this.

Her daughter, who practices Vipassana Buddhist meditation, spoke to her in awe about her clarity and peace. “Mom, this is what meditation is all about – developing the kind of serenity that you have, no matter what happens! How did you get this way?” to which she simply smiled, and shrugged, as if it were nothing. Just another day in a quietly heroic life.

I’ve watched a number of people meet their deaths over the years, or face sickness and old age, and each time I see someone exhibiting this kind of grace, I pray that I will be like them. I pray that I won’t be fussing over the annoyance of an oxygen tank or telling people to get out of the room and give me some space, but that, rather, I will welcome the presence of others with this kindness and acceptance.

My own mother was a mentor. A lifelong atheist, she told me in her dying days, “They say there are no atheists in foxholes, but here I am. I’m not afraid to die!” Her courage and strength in her final days caused everyone at the hospice to comment on her faith. This seemed a little ironic to me, so I told my Mom what those around her were saying.

She responded, “Faith is how you live, not what you believe.” And when a hospice nurse started praying over her in the name of Jesus, my Mom waved away my scowling reaction. “It’s for her, honey,” she said quietly. “It makes her feel better. I don’t mind her prayers at all.” I, ostensibly a person of faith, pray I won’t be snarling at the well-meaning nurse by my side about church/ state separation.”

Watching these beloved women, and so many others, meet their final days, tells me that faith is indeed how you live, not what you believe. Their beliefs couldn’t be further from each other. And yet, for each of them, as for the rest of us, how they’ve lived, and how they die, is truly faith in action.

Salvation

November 1, 2012I am a Unitarian Universalist who believes deeply that salvation is an inherent aspect of my  faith. Not just my own personal salvation, though through this faith that has happened, but the salvation of the world.

faith. Not just my own personal salvation, though through this faith that has happened, but the salvation of the world.

My faith is not about the salvation of individual souls for a perceived afterlife. I believe that whatever happens to one of us when this physical human life ends, happens to us all. I do not believe in the “Divine Sifting” of souls. That afterlife might be a heaven, or it might be a continuation of being, or it might be reincarnation. But whatever it is, it will happen to us all equally. We are all saved.

No, the salvation that I speak of is salvation in this world, of this world, and for this world. To use Christian language, the salvation that I believe in is the creation of the Realm of God here, and now. It is the reconciling of humanity with each other, and with the world in which we live.

This, I believe, is the vision of salvation that rests at the heart of Unitarian Universalism, a faith which calls us to work with our time, our talent, our treasure, and our dreams to heal this world, to make this world whole.

It means to work for the salvation of this world from the evils of racism and human slavery.

It means to work for the salvation of this world from the evils of war and genocide.

It means to work for the salvation of this world from the evils of poverty and inequality.

It means to work for the salvation of this world from the evils of greed and political apathy.

It means to work for the salvation of this world from the evils of torture and injustice.

It means to work for the salvation of this world from the evils of the closed mind and the closed heart.

It means to work for the salvation of this world from many more evils than this, but it also means to work for the salvation of this world by promoting the good…

It means to work for the salvation of this world by promoting the good that is found in loving your neighbor as yourself.

It means to work for the salvation of this world by promoting the good that is found in learning to love, and forgive, yourself.

It means to work for the salvation of this world by promoting the good that is found in protecting the environment, without dividing ourselves from others.

It means to work for the salvation of this world by promoting the good that is found in joining with others in communities of right relationship, be they found in the family, in the church, in the workplace, in the nation, or (could it be possible) in the world.

It means to work for the salvation of this world by promoting the good that is found in finding where your values call you to bring people together, instead of tear them apart.

It means to work for the salvation of this world by promoting the good that is found in working with others to find their own call to work for this salvation.

This is, for me, a mission of salvation… truly a mission to save the world. It is a mission that I believe must be inspired by a religious vision of what our world would be, could be, will be like when we, the human race, finally grow up. It is a vision of creating the Realm of God here and now… not of depending on God to do it for us.

This is my vision of salvation, and the power behind my Unitarian Universalist faith.

Yours in Faith,

Rev. David

Judge Not…

September 24, 2012Toward the end of the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus says to those gathered, “Judge not, that you not be judged. For with the judgment you pronounce you will be judged, and with the measure you use it, will be measured to you.” He then goes on to illustrate this nugget of wisdom with the well known analogy of noticing the log in your own eye before taking the speck out of someone else’s eye.

I experienced a moment of grace a few weeks ago in which I relearned this important message. While on vacation, I was staying in a hotel near Richmond, VIrginia. I came down to the hotel lobby for their complimentary breakfast. Also getting breakfast was an attractive, well-dressed, young woman, probably in her early 20s. She seemed to be alone at first, but after a few minutes a young man arrived for breakfast as well. He was dressed in a tank top shirt, had many tattoos on his entire body, and was wearing a ball cap tilted to the side. I didn’t take much notice of him until he started talking to the young woman in a low mumble. They sat down together, and I thought to myself, “she could certainly do better than him.” At that moment, he took off his cap, took both of her hands in his, and asked her to to say a blessing for the food they were about to eat. They both bowed their heads and prayed aloud together before they ate breakfast.

I was humbled and embarrassed that I had judged this young man based on his appearance and manner. And yet, don’t we all do this? Each of us makes some judgment, positive, negative, or neutral about everyone we encounter. Sometimes we may not even be conscious of it. As we learn in Matthew, we will also be judged, and maybe rightly so. We have to recognize our own issues, prejudices, and fears (the logs in our own eyes), before we can worry about the speck in our brothers’ or sisters’ eyes.

When we judge someone negatively, the first question we should ask ourselves is, “What is it about me and my experiences that brought me to this judgment?” Our concerns and prejudices say more about us than the person we are judging. The way to overcome this is removing the log from our own eyes first.

The next question we should ask ourselves is, “What if I’m wrong?” Chances are, unless you know someone very intimately, your judgments and preconceptions about them are at least partially wrong. How could they not be? The way to overcome this is to get to know someone better. If they are a stranger, as in my case, then that may or may not be possible. Either way, we should reserve judgment, assume goodwill, and afford each person the worth and dignity that they deserve. If we have judged someone we already know, then we don’t know them well enough, and should make the effort to better know them, which can only be done in direct relationship.

This is difficult work, but it is the essence of building a beloved community.

Every Jot and Tittle

July 31, 2012Yesterday was my birthday, so I thought I’d explain how I came about my name Matthew Tittle.

In the Christian Scriptures, in the King James Version of the Book of Matthew (5:17-18), during the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus is recorded as having said:

Think not that I am come to destroy the law, or the prophets: I am not come to destroy, but to fulfill. For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled.

In English, jots and tittles are best described as the cross of a t and dot of an i, respectively. In the original written Greek of the Christian scriptures they were iota and keraia, the smallest letter of the Greek alphabet and a serif or accent mark. In the spoken Aramaic of Jesus’ time and place, they were probably the yodh (the smallest letter in the Aramaic alphabet) and small diacritical marks, hooks, and points that help to distinguish one letter from another. The point in all three cases is attention to the smallest detail. I could say that my study of linguistics and credentials as a language teacher, combined with my theological training are my credentials for explaining jots and tittles, but I would be misleading you….The real story is this…

My parents, Mr. and Mrs. Tittle, bestowed upon me the biblical name of Matthew. They were, at the time, churchgoing folks, Presbyterians, my mother with perfect attendance for many years. So, they certainly knew that the passage in the King James Bible that read, “one jot or one tittle,” came from the book of Matthew. Hence my name Matthew Tittle is inherently biblical. That is, as long as you’re reading the King James Version of the Bible. My parents would not have overlooked this detail, especially since I know my family was focused on the gospels. You see, my older brother was Mark. My older cousin was Jon. I came third as Matthew, but my mother’s youngest sister rebelled, when her son was born, she refused to name him Luke. So we had Matthew, Mark, Jeff, and Jon. If I had been a girl, I would have been Mary, I don’t know if the intent was mother or Magdalene. So, being especially qualified to do so by virtue of my name alone, I am writing on what it means to attend to every jot and tittle in our spiritual lives! (written tongue-in-cheek for those who might think I’m serious…)

Unitarian Universalist minister Edward Frost says, “liberal faith in the perfectibility of humankind is tested to the breaking point by the daily demonstrated truths that human beings are capable of just about anything.”

We need to think deeply and attend to every detail in our practice and understanding of religion. We all encounter much that requires us to understand every jot and tittle of our own religion and that of others.

Think not that I am come to destroy the law, or the prophets: I am not come to destroy, but to fulfill. For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled.

When Jesus explains that he hasn’t come to destroy the law and the prophets, he is referring specifically to Jewish law and the teaching of the many prophets of the Hebrew Scriptures. Remember, Jesus was a Jew, and was preaching to those who knew the Jewish law and scriptures, both Jew and Gentile. He had to explain himself in this way because he had just seconds earlier done something incredibly risky by saying, in what we call the Beatitudes, that the poor, those in mourning, the meek, the hungry, the thirsty, the merciful, the pure of heart, the peacemakers, and the falsely persecuted are those who are blessed. He raised them up over the rich, those without feeling, the bullies, the well-fed, the merciless, the deceitful, the war makers, and the persecutors. He also told them, the poor, the meek, the peacemakers, and so on, that they were the salt of the earth and the light of the world, and that they needed to let their light shine. This was heretical, dangerous stuff. And so, he felt it was necessary to explain himself.

Jesus’ disciples asked him later why he hung out with such low lifes as tax collectors and sinners. He responded that those who are well don’t need a physician, but those who are suffering…

Again, he said he wasn’t trying to destroy the law. He even told the people to specifically obey and not break the Ten Commandments. But Jesus was very much an activist and even subversive. I think he was trying to change the law. He promoted nonviolence, but he also promoted active resistance. He told the people to turn the other cheek, effectively offering an oppressor the chance to take another shot, which may very well land them in trouble. He said go the second mile. Soldiers could enlist citizens to carry their gear a certain distance, but no further. Jesus suggested going the second mile, not to help them out, but to get them into trouble. He said give them not only your shirt but also your cloak. A debt collector had to leave something for people to be afforded basic comfort. The cloak was both a coat for warmth and a blanket for sleeping. It couldn’t be taken, but if you gave it to them, again those charged with protecting the law risked breaking it. And even if these measures are interpreted as gestures of good will to the authorities, the result is additional suffering on the part of the poor, the meek, the pure of heart, the peacemakers. The result either way is that the weak are really the strong. They are the blessed. To invoke a phrase from Joel Osteen of Lakewood Church across town, “the victims are the victors.” Or as he says to his congregation “Be a victor, not a victim.” A sound soundbyte.

I am not come to destroy, but to fulfill.

What was he fulfilling? I think this is the key to the whole passage. Traditional interpretations suggest that the meaning here is nothing short of eschatological– the end times, the fulfillment of the apocalypse, and final judgment. I think that modern Christianity would be a wholly different and even more appealing religion if the book of Revelation had been left out. Which it almost was. Some even tried to have it removed as recently as a few hundred years ago.

If we separate the wheat from the chaff (to invoke another biblical nugget), we find that the heart of Jesus’ teachings (the wheat in this case), was almost exclusively devoted to the theme of love and care for one another, neighbor, and enemy alike. It was for the creation of a beloved community. His message was one also of personal empowerment of those who were considered the least among us. He told them time and again that faith would heal them. Faith comes from within. Faith is the very hardest thing in the face of truth, which is why he spent so much time trying to empower them to overcome adversity through faith.

For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled.

This first phrase, “For verily I say unto you” in the King’s English (I’m sorry I don’t have the Greek or Aramaic on the tip of my tongue) is universally interpreted by biblical scholars to be an attention getter. “Hey folks, listen up, you better believe me when I say…” My own paraphrase of the rest of the passage goes like this: “Hell will freeze over before even the smallest detail of the law changes, until all is fulfilled, until you do something about it. Don’t go breaking the law, but change it so that this beloved community can be formed.”

After going through a few examples, he told these underdogs that until their righteousness exceeded the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, until they became victors and not victims, that they would not enter the kingdom of heaven. The scribes and the Pharisees were the recorders, and the interpreters and the enforcers of the political, social, and religious law. Jesus was saying that those who suffer, those who care, those who are oppressed, those who look out for the world, are as well and even better equipped for the task of interpreting the rule of law, than are those charged with doing so.

The kingdom of heaven that he refers to isn’t in the hereafter as many would have us believe. It is here and now. We can create heaven or hell here on earth. Human beings are capable of almost anything. Nothing is going to change until we change it. We need to attend to the details of our spiritual lives. We need to challenge the status quo, as Jesus did, so that we can bring about heaven here on earth. We can sit back and watch and do nothing and feel sorry others, or feel sorry for ourselves. But this would be the worst sin of all.

Over the past few years in the United States many have been criticized and ostracized, and persecuted for doing just what Jesus did–for dissenting–for being critical of the status quo and of those in and with power. But this is our task. This means speaking out, and more importantly, acting out in the world. It means knowing who you are spiritually, and being as certain and secure in that faith as are the scribes and Pharisees of our times. If we shy away from this moral imperative, “Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law.”

Going to the Movies

July 7, 2012“What we are today comes from our thoughts of yesterday, and our present thoughts build our life of tomorrow: our life is the creation of the mind.” the DHAMMAPADA

This summer, I decided to use contemporary movies as the “texts” for the worship services at my congregation. Partly, this was because I hadn’t been to any movies for several months and this gave me an excuse to go to the movies in these hot summer months. But more than that it is because of the importance of stories, and movies are our contemporary shared stories.

Since humans have had consciousness and language, we have been telling stories. We all have stories; in some ways, we are stories. They are our memories; they are our dreams. Stories are how we share what is important and meaningful to us. They are how we tell each other who we are. Indeed, stories are how we tell ourselves who we are.

Some stories intrigue or entertain us and other stories distress or bore us. The first human stories were told, heard, remembered and re-told. Then the stories were written and collected. Some of those stories became sacred through re-telling. They gave communities identity and meaning. The stories explained the world, life and death. Some of those story collections came to be called scriptures which is a word that means writings. People still think about and learn from these old stories. We still tell, remember, write and read stories. But now a primary way of telling and receiving stories is through television and movies. We think about, talk about and learn from what we watch as well as what we hear. Film can be powerful and emotional. So, I decided this summer to talk about current movies, to see what we can learn from these films. What are the messages in these contemporary stories?

Of course, there can be many messages even in one movie, and as we watch a film, our own experience influences the message we receive. One theme that I experienced in the three movies that I have seen so far may well be part of every movie. The movies are The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, The Kid With A Bike and The Intouchables. In many ways, these are three quite different films, but all three show how we are transformed in relationships, especially in caring relationships. The movies’ stories are about love, courage and transformation, and because they are stories about life, they are also stories about loss and acceptance.

Authentic, open hearted and mutual relationships allow us to accept our sorrows and our joys and to become more of our own true selves. Even brief encounters if honest and open to the other can change us, and movies, too, have the potential to change us. Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, the brothers who made The Kid With A Bike, said of their films, “The moral imagination or the capacity to put oneself in the place of another. That’s a little bit of what our films demand of the spectator.” When we are our best selves, that “capacity to put oneself in the place of another” is the gift we give each other.

May your stories be heard and may you be open to others’ stories.

On Being a Murphyist

July 5, 2012I have spent the last seven years in the occasional study of a religious system that I believe has always existed, but has never been academically defined (except perhaps in secret by some graduate engineering students). My interest in this religious system is that my wife is an adherent, and in order to better understand her I needed to have a deeper understanding of her religious faith. Through that study, I have come to realize my wife is far from alone… that tens of thousands, if not millions of people believe, either explicitly or implicitly, as she does.

always existed, but has never been academically defined (except perhaps in secret by some graduate engineering students). My interest in this religious system is that my wife is an adherent, and in order to better understand her I needed to have a deeper understanding of her religious faith. Through that study, I have come to realize my wife is far from alone… that tens of thousands, if not millions of people believe, either explicitly or implicitly, as she does.

The name we have arrived at for this religious system (and a quick search of the internet shows we are not alone in this either) is Murphyism. At its core, it is the religious belief that the principle known as “Murphy’s Law” (Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong) is the guiding and unifying principle of the universe.

I will say from the outset that this article is a little tongue-in-cheek, but only a little. Perhaps because I am not a Murphyist I cannot fully grasp the seriousness with which the adherents of this faith take it. I know how serious it is, because I have seen it in this woman who has been my friend for 17 years, and partner for the last 10. So, I will attempt to place my own misguided lightheartedness aside, other than to say that if you find this article ridiculous, then you are not a Murphyist… but if it seems ironic to you, then you just might be a Murphyist…

I will also mention that this article has been approved by my wife, the Murphyist…

If you ever find yourself making backup plans for your backup plans… you might be a Murphyist. If you have ever dated someone because you think they might be “lucky”… you might be a Murphyist. If you are really interested in the results of crash tests when buying a car… you might be a Murphyist. If you set more than one alarm clock when you go to sleep at night… you might be a Murphyist. If the first thing you notice about a new room is the number of fire exits… you might be a Murphyist. If you look at a glass and see it not as half-full (optimist) or half-empty (pessimist) but as something that might spill on you… you might be a Murphyist. If you have thought up new things that you do that could fit within this paragraph… then you might just be a Murphyist. I’d love to hear those new “You might be a Murphyist if…” one-liners.

As with many religions, the origins of this one are shrouded in myth and mystery. The modern wording of this “truth” goes back at least 150 years, although there is evidence that it was old even in that time. Its initial modern codifications began in the fraught-filled field of military engineering, and some have traced the initial prophet Murphy to an Air Force Engineer in 1949… but even this is shrouded in mystery and controversy. As best as I can decipher the legend, it was the colleagues of an Air Force Captain named Ed Murphy who first noticed that he had an inherent penchant for disaster… and named the law appropriately.

At the core of this religious faith rests the immutable law “Anything that Can Go Wrong, Will Go Wrong”. This however is just the beginning of the religion, for from this center flows an entire theology. I have identified two separate branches of Murphyists: Secular/Rational Murphyists and Religious/Mystical Murphyists.

Secular/Rational Murphyists are those who believe that the workings of this law can be demonstrably shown to be an inherent part of the universe through observation and the scientific method. They do not perceive their Murphyism as a religious system, and often do not perceive themselves as religious at all. They can often be found in engineering and the physical sciences. The scientific method, with all of its checking, double checking, verified and reproducible results, is a comfort for them, yet they are not surprised when it does not work. They believe that Murphy’s Law itself exists and operates independently of any being or intelligence. Like gravity, it is a fact of existence. Its universality is a comfort for them, for they are able to say that, also like gravity, the law operates equally among all people… and any perception they might have that they seem to have worse “luck” than others must just be perception, not reality.

For the Religious/Mystical Murphyist, nothing could be further from the truth. They are deeply aware that the “Law” does not apply to all people equally. The experiences of their lives have convinced them that some people are more prone to the effects of this “Law” than others, and they sense a mischievous divine intelligence behind this fact. They look to past religious traditions that name “trickster” gods such as “Loki” and “Coyote” for their ancient sourcing. Put simply, the Religious/Mystical Murphyist believes that they are the “chosen” of the God Murphy, and often feel like a small mouse that a cat plays with. The God Murphy is a fickle, trickster God who cannot be appeased, only mitigated and suffered.

The Rational/Secular Murphyist believes that:

Murphy’s Law is the primary, guiding law of the Universe.

Murphy’s Law applies to all situations and all people equally, though humans may not always perceive its workings.

Systems such as the Scientific Method have been developed to allow humanity as a whole to mitigate the effects of this law upon progress.

Everything in human life should be checked at least three times by two or more people before it can be trusted, and then that trust should only be provisional.

When systems such as the scientific method and other checks are used and things still go wrong, there is no guilt or fault that attaches, because the universe is designed to go wrong (Chaos theory). You just find out how it went wrong this time, correct for that, and try again.

The Religious/Mystical Murphyist believes:

Murphy’s Law is the primary, guiding law of the Universe.

Murphy’s Law is manifested by a trickster God, named Murphy.

The effects of Murphy’s Law are not manifested equally throughout the universe. The God Murphy has chosen some human beings to be his “favorites”. They experience the effects of the law more profoundly than others.

The God Murphy cannot be appeased… only mitigated.

Some human beings, often termed “lucky” are mostly ignored by the God Murphy. Though this is unfair, it is simply the way things are.

Those who are the “chosen favorites” of the God Murphy have developed ways of living their lives that mitigate the effects of being the “chosen” of the God Murphy. Some of these strategies include always having multiple backup plans, utilizing all possible safety equipment, and spending time with (and sometimes becoming life-partners with) those that they perceive to be “lucky”, hoping for some balancing effect.

When things go wrong, Religious/Mystical Murphyists realize that is it probably not their fault. Fault only attaches if they can identify some precaution that they could have reasonably taken that they did not. If they took all reasonable precautions and things still went wrong, then the Religious/Mystical Murphyist remembers the God Murphy and seeks to mitigate any and all effects.

Each of these religious systems begins and ends in the same place… and in this beginning and ending lies the strength of each of these systems that I wish to hold up to close this article. I look forward to hearing from the Murphyists out there as to how well I have captured a snapshot of your religious system, as I am one of those “lucky” one’s that a Murphyist has married to seek some kind of cosmic balance. I freely admit that I am only seeing part of it, having not lived the reality myself.

The strength in each of these religious system is that they begin with a firm ideological foundation (Anything that can go wrong will go wrong) and the end with a way to place the fault for things going wrong on something besides the self, so long as one has done the hard work of precautions and testing that is the spiritual practice of the Murphyist. Thus, taking precautions, developing backup plans, testing possible results, cushioning consequences, purchasing safety equipment, etc… all of these become an intimate and intricate dance in the life of the Murphyist, be they religious or secular, rational or mystical. The Murphyist is called to live a life of preparation, knowing that all preparation will ultimately fail. However, if they can prepare well enough, then the God Murphy can shoulder any blame. The true Murphyist becomes an expert at “picking up the pieces” of that failure and trying again. It is all they can do.

As I believe that all good theology should have a Science Fiction analogue, I have found such an analogue for the Murphyist. If you reach deep into Science Fiction you will find, within the Universe inspired by Larry Niven, a race of beings known as the Puppeteers. They live on a world with no hard edges, no corners, and no surfaces that are not cushioned. They prepare constantly for any danger, mitigate any threat, and seek safety as their primary purpose. Any Puppeteer who seeks adventure is declared criminally insane, and immediately exiled. When they sensed the impending energy-death of the Universe, they moved their entire solar-system to an area of the universe that would last longer than others.

As I believe that all good theology should have a Science Fiction analogue, I have found such an analogue for the Murphyist. If you reach deep into Science Fiction you will find, within the Universe inspired by Larry Niven, a race of beings known as the Puppeteers. They live on a world with no hard edges, no corners, and no surfaces that are not cushioned. They prepare constantly for any danger, mitigate any threat, and seek safety as their primary purpose. Any Puppeteer who seeks adventure is declared criminally insane, and immediately exiled. When they sensed the impending energy-death of the Universe, they moved their entire solar-system to an area of the universe that would last longer than others.

If such a world appeals to you… then you might just be a Murphyist.

Yours in faith,

David

A Moving Experience

June 23, 2012My ministry in Philadelphia has led me to have two homes: a house in Central Pennsylvania with my husband and an apartment in Philadelphia near the church. This week, my husband came to Philadelphia to help me to move to another apartment. As with many things in my life, this moving experience has led me to reflect and to pay attention. It is a good change, but all change has consequences.

Neither apartment is large, but the new one is big enough to have a separate office space and to host small groups. I say this so that you will know that this move was not like changing houses. Still, there were boxes of books and papers, boxes of dishes and kitchen equipment, and the basic furniture. We are no longer young, so for the first time in our adult lives, we hired some men to help us move the furniture. They looked at the furniture and said, “Oh, this is easy it’s just furniture!” It would not have been easy for us. Moving reminded me of my need for help and my appreciation for that help, both volunteer and paid. Change often means that we need help. I am grateful for community. I am grateful for caring relationships.

Rick and I moved all the boxes and all my clothing. Did I mention that the new apartment is a second floor walk-up? There are actually four flights of stairs. Most of the time, this is nothing, and I prefer having stairs so that some exercise is built into my days. Did I mention that it was the hottest day of the year so far? The morning after we carried all these boxes, I wasn’t sure I could move my body at all that day. At first, walking across the room seemed out of the question! I could and did! Moving led me to pay attention to my body and to be gentle with myself about my physical limits. Change means that we do different things. I am grateful for what I am able to do.

How could it be that I had so much stuff in a one bedroom apartment in two years of being in Philadelphia? Do I really need all that stuff? The answer, of course, is no, I don’t really need all that stuff. Some of it I gave away before the move, and some of it, I am sorting and giving away after the move. Figuring out how to use things or where to put things in a new place helps me to see what I have. There is an inertia, a not seeing, that comes from having things in the same place. Moving overcomes that inertia. Moving reminds me of my desire to live simply. We have not changed houses for 18 years. I think now would be a good time to simplify. What is in o ur house simply because of inertia and not because we are using it or will use it? What is in my life simply because of inertia? Change allows us to see things in a new way. I am grateful to see new possibilities.

Another reminder in this move came from my cat, Annie. Annie was terrified by this move. Of course, she could not understand what was happening. When she arrived at the new apartment, she ran to a dark place and hid. She only emerged wide-eyed and jumpy when I opened a can of cat food. Annie saw where I put the food and took a bite. She ran to her hiding place again. She came out crying. I petted her and showed her the litter box. She hid again until we went to bed when she started crying, only stopping when she was held and comforted. Her reactions remind me that change can be distressing especially when we do not understand what is happening. By morning, Annie was fine. She stopped crying. She knew that her needs would still be met. Food, litter box and her people were all available. She found the windows for entertainment. She slept comfortably. Annie reminded me that we all need comfort. We may need time to become comfortable with change. We can accept change more easily when we understand what is happening. I am grateful for the comfort of caring relationships. I am grateful for understanding. I am grateful for awareness.

May we all be aware of gratitude.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210