What Bowling Taught Me About Patience

January 31, 2014A couple of week’s ago, on a cold Chicago afternoon, after being cooped up for most of the week, my husband and I looked at each other and said, “Let’s go bowling.”

Now, nothing says wholesome family fun quite like putting on some smelly communal shoes and listening to drunk men swear at the football game, but after being cooped up in the house for more of the week, we were just a little bit desperate.

Matt and Jack have gone bowling together a few times, but this was the first time that Teddy had been bowling. After trying on three (three!) different pairs of shoes, convincing him that the bowling ball that looked like Darth Maul was too heavy for him (he’s just a tiny bit obsessed with Star Wars), and showing him how to put his almost-four-year-old fingers in the ball and roll it down the lane, he was ready to go.

“Self! Self!” he stubbornly said in true Teddy fashion.

He walked to the line holding the ball with both hands and I have never been more certain that a trip to the ER for a broken toe would be in our near future. (By the grace of God, he made it out of the bowling alley with all ten toes intact.)

For ten frames, Teddy grabbed his ball, stepped up to the line, and heaved the ball as hard as he could down the lane. Most of the time, he rolled the ball right into one of the bumpers and it would sloooooowwwly bounce its way down the lane. On each of his rolls, the ball moved so slowly, in fact, that I was pretty sure that it wouldn’t make it to the pins. And, more than a few times, Matt and I exchanged a look that said, “Which one of us is going to ask the surly desk attendant for help when the ball stops in the middle of the lane?” (Fortunately, we never had to answer that question, but for the record, it would have been him.)

On every one of Teddy’s turns the ball moved at a snail’s pace, barely moving down the lane until, finally, it would make it to the pins and maybe even hit down a few. As one of THE most impatient people on the planet, I found the delay to be a bit unsettling at first. Waiting for the ball to plod down the lane, I felt nervous, jittery, and antsy.

But, after a few frames, I realized that what I was feeling wasn’t actually impatience; it was fear. Fear that the ball would never make it, fear that we’d have to ask for help from the surly man at the front desk, fear that Teddy would end up in a tantrumy heap of tears.

But, after a few frames, I realized that the ball would eventually make it to the pins even though it looked like it might stop moving at any moment. And with the fear of not making it subsiding, the waiting actually became the best part of it all. Because in the waiting, I had time to soak it all in. I could watch Teddy’s eyes light up as the ball moved down the lane, I could steal a few glances at my husband, and I watch my older son add up the scores on the screen.

Once the fear of never became the confidence of eventually, I was able to look at the waiting and the slowness in a whole new light.

And I wondered: How many other times have I mistaken fear for impatience? Fear of the never or the always. Fear of the falling and failing. Fear of dead ends and asking for help. Fear that without the end, the means just don’t matter.

And in this fast-paced, frenzy to get something or do something or hit the target, how much has gone unnoticed and how much enjoyment have I missed in the slow-moving journey?

I’ve been struggling a lot with impatience lately, wanting things to happen now, now, now. But I am realizing that this need for things to happen on my timetable is less about fulfillment and satisfaction, and far more about fear. Fear of losing control, fear that I will never make it, fear that I am somehow lacking just as I am and right where I am, fear that I won’t be satisfied until the pins are knocked down so to speak.

We tell ourselves that when the pins are knocked down, then we’ll be happy. When we get married, when we have a baby, when the kids are in school, when the kids are out of the house, when we get the job, when we get the promotion, when we are out of debt, when we buy a house, when we get an agent, when we get published, when we receive this award, when we land that sales account, when…, when…, when…then we’ll be happy. And all the while, the ball is moving slooooowwwwly down the lane and there is so much going on while it rolls if only we’d just notice.

The ball moves slowly, more slowly than we’d like, many times. And we wait and we wait and we wait, growing increasingly tired of all the waiting and more fearful that the ball might actually stop. And in all of that fear, we miss it. We miss the twinkly eyes and the emotions, the bouncing back and forth and the graceful movement to it all, the sights and sounds and people and various goings-on that are actually a really big deal if we’d just stop focusing so much on those damn pins at the end of our lane and trust that the ball will eventually get there.

After bowling for a few hours last Sunday afternoon, and watching the ball move slowly down the lane, I realized a few things. I realized that the ball will slowly, eventually, finally reach the pins; it just takes a little longer sometimes. I realized that if the ball does stop, you can always ask for help (even if you have to ask the surly man behind the desk), get a new ball, and roll again. And, most importantly, I realized that there is so much good stuff going on while we wait for whatever it is that we’re waiting for.

So take your time. Pay attention. Enjoy the journey.

And know that, even when the ball moves slower than we ever thought possible, that at least the pins are happy for few extra moments of peace.

This post originally appeared on the author’s website at www.christineorgan.com.

Worthy to be Entrusted

January 26, 2014 (Today, I preached at the ordination of a new minister in my denomination, Unitarian Universalism. Her name is Rev. Lara Campbell, and I shared the pulpit with Rev. Michael Tino. Here is my half of the sermon.)

(Today, I preached at the ordination of a new minister in my denomination, Unitarian Universalism. Her name is Rev. Lara Campbell, and I shared the pulpit with Rev. Michael Tino. Here is my half of the sermon.)

“Do not demand immediate results but rejoice that we are worthy to be entrusted with this great message,” wrote Olympia Brown, the first woman to be ordained by a denomination—the Universalists, in 1863. And we know that she did not demand immediate results, she who worked for women’s right to vote from girlhood and finally was able to cast a ballot in 1920 at age 85.

I think of Olympia Brown, loving this faith despite the widespread discouragement she had to face in order to be ordained and the challenges she faced in ministry her whole life. I think of Egbert Ethelred Brown and Lewis McGee and so many other groundbreaking ministers of color who fought, against resistance and sabotage, for the right to lead Unitarian and Universalist congregations, who stood by this faith. And I think of all the people who still struggle to be able to devote their gifts to this faith, for a variety of reasons.

We do not demand immediate results but rejoice that we are worthy to be entrusted with this great message, their lives say. Their ministries say. Their legacies say. Their legacies are very much with me tonight as I preach, for the first time, wearing a stole given to me after the death of one of my mentors, Rev. Gordon McKeeman, who died in December. Gordon, a stalwart Universalist, who devoted his life to this faith, is now here with us, lending strength and companionship, reminding me that he has entrusted me with leadership, reminding us that he entrusted his life to Universalism and ministry.

I think of these people and I think of all the bold, visionary Unitarian Universalist ministers, ordained and not ordained, right now, some of you sitting right here, who have dreams of new applications for our faith, who believe that our faith calls us to stand with those lofty ideals of equity, justice, lovingkindness, in this miraculous yet devastating world. Who imagine ministries with unusual new shapes and contexts and methods, all of which seek to bring more love into the world.

I think of ministries beginning in coffee shops—Beloved Café, envisioned by seminarians at Starr King School for the Ministry—and yoga classes—Create Meaning, out in Denver—and in the streets—Faithful Fools, which has been inventing street ministry for decades now—and AWAKE ministry in Annapolis, and the Sanctuary in Washington DC—all bold, visionary new shapes for our future. And each week, with the Church of the Larger Fellowship, we live into these new shapes as we try new ways to find each other, to care for each other, to care for our word from all across the globe.

And deep within me, I say, yes! I am so grateful that you stand by this faith! All of you! All of us! I am grateful that so many work for it and sacrifice for it! I am grateful that all of us are here today, attesting to its value, when we could be doing so many other things on a Sunday afternoon!

But then, right there with the yes, something in me whispers, but…just a little whisper that says, but.. yes, but… but I wish you, and I, didn’t have to dream our dreams alone so much of the time, wish some of our best and brightest lay and ordained ministers weren’t still fighting for support the way that Olympia Brown and others have had to fight for support. I wish each vision could be surrounded by others who supported vision and faith, that we could find ways to reach out better beyond our individual enterprises and make common cause, collaborate with one another, build something bigger than our congregations.

In this era of union-busting, I am longing for a Spiritual Union. I want spiritual collective bargaining. I love Unitarian Universalism, and I love the way that our congregations are self-determining and unique, but I believe in those old songs that I was raised on, about how “The Union makes us strong.” I take to heart those words in our hymnal from Dr. Martin Luther King, “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” And I say, when do we realize that we are that garment, instead of behaving as if our purpose on the planet is to pull apart the threads?

What might we do if we embodied a place of spiritual union with one another? When I say we, I don’t mean only Unitarian Universalists, I mean all of us who believe that people are worthy to be entrusted with carrying and sharing love so deep it will not let us go? What if that name that’s been assigned to us when we wear bright yellow shirts that say Love on them, The Love People, was really our identity? What if we cast fear aside, if we dared to believe that humanity, collectively, is worthy to be entrusted with the message that there is power of love so big that it can’t be held by any one set of religious metaphors and beliefs?

And who might we entrust with our faith? Who might we trust as prophetic voices in our wider faith, a faith not bound by traditional buildings or denominational stakes in the ground? How might we live into spiritual union with the people whose leadership we need in order to challenge and take down the notion of the saved and the damned, the chosen and the unchosen, the deserving and the undeserving, which dominates the US and so many other countries as much now as it did when John Calvin’s concept of predestination, that some are born saved and some are born damned, was widely believed to be true?

Where might we find union and create more love with other people, of every faith and no faith, who dare to proclaim that all people have inherent worth and dignity? Where are the voices saying, YES, African American youth and other youth of color, you are worthy to be trusted! Youth of color, queer youth, youth in general—you are worthy to be trusted! You are the people we need to have as union stewards in our spiritual union.

Where are the voices insisting, YES, people on public assistance, you are worthy to be trusted! More spiritual union stewards, whose leadership we need. Where are those whose witness proclaims, YES, immigrants without all your legal documents in order, you are worthy to be trusted! We need you as leaders in our spiritual union.

What might we do? Who might we dare to be? We have seen some of this in our work for marriage equality, immigration rights, voting rights, in our anti-racism work, as we join other religions and organizations and people to work together, but what if we had real spiritual union?

Whatever configurations our ministries with one another and the world take, whatever architecture we use for buildings, whatever technologies we employ, our own sense of Unitarian Universalism’s worthiness must be a part of the structure. But the time for clinging to small identities is over. The world is far too small now, we are too closely connected to even imagine that we do not have neighbors on every side who care about what we care about.

It’s scary. It means letting go of so many structures and identities that we have confused with worthiness—structures of privilege, or comfort. It means swimming in the ocean rather than in the small pond which our relational faith can become. But love will save us, again and again, when we are afraid, when we are confused, when we make mistakes, when we can’t get our bearings.

We are worthy to be trusted, not because Unitarian Universalists are the chosen people. Worthy, instead, because we have devoted ourselves to faith in a force–call it truth or God, life or love–a force much bigger than we are ourselves—which will not let us go, and which will not be confined or defined.

We have been entrusted with a great faith, and that faith whispers, shouts and sings, You are worthy! Worthy to wear the mantle of this great faith.

On Building Bridges

January 3, 2014

“We build too many walls and not enough bridges.”

Isaac Newton

About five years ago, I sat in church one cold and dreary Sunday morning while our pastor, Jennifer, talked about bridges. I came into church that morning a little lost, a little frustrated, and utterly exhausted. I didn’t really want to be there and I had been feeling so beaten down by life that I seriously doubted whether words of spiritual advice would make any difference whatsoever.

Nonetheless, I sat in that small church, distracted, and I listened to her talk about shoveling sidewalks and neighborhood parties and wide nets. She talked about the sacred act of building and strengthening bridges, about maintaining and honoring those bridges, and she then issued a challenge to us to become bridge-builders ourselves.

At the time, her words fell on a weary soul and an exhausted body. With a two year old at home and mountains of stress, I wasn’t looking to build bridges; I was just hoping to survive the day and maybe take a nap. Yet, somehow her words rang true and they stuck with me ever since.

On some intrinsic level, I think that we are all called – whether by God, some higher power, or the human condition – to be bridge-builders. We are naturally driven, I suspect, in some deep primal way, to want to connect, to build bridges – in our families, social circles, communities, and workplaces; with the natural world and the spiritual world; with others and even within ourselves.

But, what does it mean to be bridge-builders?

While we are called – compelled even – to be bridge-builders, it is not always an easy task. In fact, I think that it just might be one of the hardest things that we, as imperfect and ego-driven humans, are asked to do. Bridge-building is awkward and daunting and painful; it is clumsy and uncertain and utterly exhausting. Bridge-building means uncomfortable conversations and bruised egos and being the first one to say “I’m sorry” or “I love you” or “I was wrong.” And bridge-building requires a healthy dose of faith, copious amounts of forgiveness, and an infinite amount of grace.

I would be lying if I didn’t say that my ego and heart haven’t ached just a little bit when, after introducing some friends, they prefer each other’s company to my own. I would be lying if I didn’t say that doesn’t take frequent reminders to check-in with extended family and friends during those times when life’s obligations leave little room for anything beyond carpools and homework, conference calls and emails, paying bills and folding laundry. I would be lying if I didn’t say that I have to constantly fight the urge to wear my Facebook mask, to present a Pinterest-worthy picture of my life to the world, to pretend that I’m not constantly second-guessing myself. And I would be lying if I didn’t say that there have been times when the time and energy spent building bridges hasn’t left me feeling scared, inadequate, and completely drained.

There is a natural tendency, I suppose, to preserve, protect, defend, and maintain the status quo. We get busy and beaten down with the day-to-day stresses and the curveballs that life throws at us, and sometimes bridge-building just seems like too much work and a colossal waste of time.

But bridges aren’t built when we stand our ground and stay in our comfort zone; they aren’t built when we focus on relationship maintenance, rather than relationship sustenance. Bridges aren’t built in the masks or by pretending that we aren’t scared and confused. Bridges aren’t built when we snicker at the expense of another, when we think in terms of “us-them” and “the other,” or when we focus all they ways we are different.

No, bridges are not built this way.

Bridges are built when we cast a wide net, when we make the effort, when we are radically inclusive. Bridges are built when we ask questions and take the time to listen to the answers. Bridges are built when we lay ourselves bare and stumble through the muck; when we make an intentional and difficult decision to forgive; when we focus on our shared and common human condition. Bridges are built when we step into the heart and mind of someone else; they are built with a single phone call or email, with a tender touch, with an open mind and a generous heart.

Bridge-building is hard, hard work. But bridge-building is good work, beautiful work, essential work. Bridge-building is holy human work.

There are bridge-builders all around us, and we can be bridge-builders ourselves, whether we know it or not. With her prophetic words about neighborhood parties and shoveling sidewalks and taking the first step, Pastor Jen built more bridges for me than she could possibly know. And for that I am eternally grateful and continually inspired. We have both since moved away from that church community in Chicago, me to the suburbs and she to California and then Virginia. But I have no doubt that she has been continuing to build bridges along the way. Because once a bridge-builder, always a bridge-builder.

Who are the bridge-builders in your life?

The Language of Faith

November 1, 2013

Source: Google Images Creative Commons

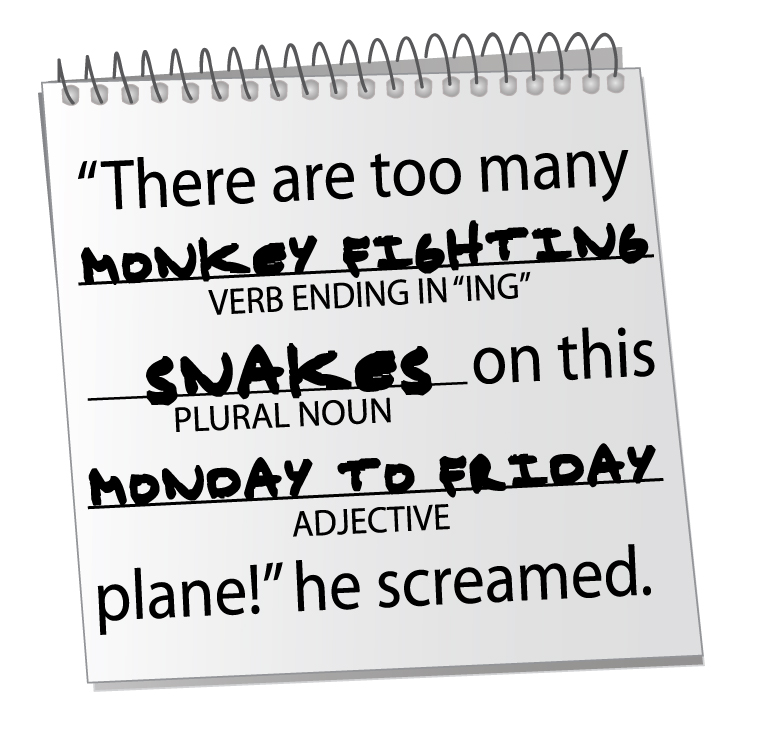

Last Sunday, while out to lunch with my husband and two young kids, we passed the time waiting for our food by playing Mad Libs. As you might remember, Mad Libs is a word game where one player asks another player to provide a particular kind of word – noun, verb, adjective, etc. – to fill in the blanks of a story. After the words are provided, randomly and without context, the other player reads the funny and often nonsensical story aloud.

If you have ever played Mad Libs, you know just how important grammar and semantics are to the art of storytelling. You also realize just how important words and context are to communication and understanding.

Words are, obviously, incredibly powerful tools. We use words to communicate, to connect, to explain, to inform, and to educate. But words have significant limitations, as well. Unfortunately, all too often words are used as a weapon instead of a tool. We use words to restrict instead of expand, to assume instead of discover.

Ironically, we often try to use language to define those things that are undefinable. We try to explain the inexplicable with rational, but overly simplistic, definitions. We fit people into our prepackaged labels –believer, nonbeliever, Christian, Jew, Muslim, atheist, humanist, idealist, pacifist, liberal, or conservative – and we try to make sense of this crazy, nonsensical, Mad Libs-like world with assumptions and categories.

But when it comes to the Big Questions, to matters of the Heart and the Spirit, there are no definitions. There are no labels. There are no prepackaged boxes.

Quite simply, language fails us when it comes to matters of the Spirit. God (I use the word “God” knowing that the word itself has its own limitations) comes in many names and is experienced in many ways. God and all things Spiritual, by their very nature, are unknowable and personal; they are felt with the heart and cannot always be adequately explained with words.

But, being the intelligent humans that we are, we try to explain that which is deeply felt with words, explanations, and sound bites. And, as a result, any inherent commonality to our human spirit gets lost, the beautiful complexity of differences gets diluted. The words – and labels – that we use become more important than the ideas.

So much division and dissention is created and exacerbated by the labels and linguistic limitations that we put on matters of faith and spiritual belief – concepts that are, quite frankly, too big to fit into any label or verbal representation.

Perhaps, we need to focus less on the words of faith and more on the language of faith. Perhaps we need to stop getting lost in the semantics of God and, instead, learn the languages of God – ones that are spoken and heard in a number of ways.

Music has always been my language of God. I love to sing (off-key) and can clumsily tap away a few songs on the piano, but I am far from what you would call “musical.” Yet music has always been a profoundly moving spiritual experience for me. Whether I’m swaying to a church choir singing “Amazing Grace,” listening to Bon Iver on my iPod, singing along to Bob Dylan in the car, or dancing like crazy with my kids in the kitchen, few things have the power to move me like music. Music creates an internal communication with the Spirit that washes my soul clean, as if I have stepped into a warm shower with the lyrics and melody rinsing away the grit and grime of everyday life.

Spiritual language can be found in any number of ways. My grandpa spoke the language of God through his generous hospitality. It was nearly impossible not to feel like THE most important person in the world when he greeted you. Others feel the language of God through the earth and nature. Gardening, for my paternal grandma, was so much more than a household chore, it was a spiritual practice unto itself. With her fingernails soiled and her hands calloused, as she tended and cultivated, she spoke a spiritual language that only her soul understood, that only her Spirit could appreciate.

Some people speak God’s language through art or poetry, photography or painting, teaching children or caring for animals, caring for the sick or sharing a meal with friends. Shauna Neiquist wrote in Bread and Wine, “When the table is full, heavy with platters, wine glasses scattered, napkins twisted and crumpled, folks askew, dessert plates scattered with crumbs and icing, candles burning low – it’s in those moments that I feel a deep sense of God’s presence and happiness. I feel honored to create a place around my table, a place for laughing and crying, for being seen and heard, for telling stories and creating memories.”

Let’s face it, we live in a chaotic world, where the unimaginable meets the incomprehensive, and devastating realities mix with everyday miracles. We want to make sense of it all. Of course, we do. In our well-intentioned, but misguided, attempts to explain, understand, and communicate, we look to definitions and labels. We rely on assumptions and suppositions, and we look to linguistic placeholders to meet the expansive scope of faith, God, and the Spirit.

We try to define the indefinable.

But maybe if we spend a little less time focusing on definitions of God and labels of faith, and instead focused on feeling the complex languages of God, maybe then we could gain a better understanding of each other and ourselves.

Season of Forgiveness

September 8, 2013The spiritual practice of atonement, asking and offering forgiveness, is a practice that actively builds and sustains a robust and healthy beloved community.

When we are willing to take the risk of showing up to each other in all of our gloriously imperfect humanity and begin again and again in love – we are being faithful.

When we are willing to go deeper with our friends and family and neighbors, willing to understand their fears and difficulties – to do more than work with them side by side for years without knowing what causes them pain or brings them joy– we are being faithful.

In Jewish tradition, the Book of Life is sealed on Yom Kippur, not to be reopened for another year at Rosh Hashanah. For Unitarian Universalists, the book is never sealed. Each day is an opportunity to begin again in love, repenting and offering forgiveness as often as is required for the health and well-being of this beloved community.

What harm have you caused in the past year that requires repentance? What do you need to forgive yourself for? Who needs your forgiveness?

Weathering

August 8, 2013When the storm comes in

a bird sits on a limb in the

suddenly solidly still

humid air. I watch

weather radar, listening

to a child scream nearby–

is it joy or fear?

I raise a glass of ale

brought to me

all the way from London.

I read the storm

warnings with interest,

large hail; damaging winds . . .

Is this another storm

that I will weather?

Sometimes yes;

sometimes no;

prognosis: probable.

I raise a glass of ale

all the way from London.

It’s always storming somewhere.

There’s always a glass

of ale somewhere.

And the screaming.

And the screaming.

A Former Member Asks the Minister for a Favor

May 9, 2013She says her family

shuns her. She says

it has something to do

with God. She says

the cancer has gone

way too far. She says

when her brother died

the family pastor said

he went straight to hell

and “Let that be a lesson.”

She says, “Will you do

my funeral?” A light rain

falls on the lake,

circles in circles.

On “Faith”

Faith is a noun. It’s a person, place, or thing.

An online etymology site tells me it came into English in the mid-13th Century.

The word means, the site tells me, “duty of fulfilling one’s trust.”

The word comes to English from Old French: feid, foi, which meant “faith, belief, trust, confidence, pledge.”

The word came to Old French from Latin: fides, which meant “trust, faith, confidence, reliance, credence, belief.”

The word ultimately derives from from the oldest known ancestor of English, Proto-Indo European: *bheidh- which also gave us the Greek word for faith, the one that appears in Christian scripture, pistis.

The dictionary notes that the word in its theological sense dates from the late 14th Century. Meaning this: What religions today mean by faith, as in “you gotta have faith,” did not exist as a concept when the Christian scriptures were written.

I’m just sayin’ . . .

See for yourself: http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=faith

YOU GOT PEOPLE

December 14, 2012You Got People

This Public Service Announcement brought to you by a Unitarian Universalist minister who has just been creatively reminded by the universe of this important truth.

Beloveds, in the crush of this season of holidays, remember that YOU GOT PEOPLE.

Contrary to the images of loneliness and unworthiness being projected onto us during this commercialized season – you are intimately and ultimately connected to all of creation.

Whether you buy or receive holiday gifts, send cards, light menorahs, kinaras, or bonfires – during the longest nights of the year and during the longest days and every time in between, you are not alone.

The myth of our culture is one of worth based on stuff and perfection.

The myth of our culture says you have to earn grace.

The myth of our culture is deeply isolating and numbing.

These are not life affirming myths.

These are not myths to live by.

Sister Joan Chittister declares that “The paradox is that to be human is to be imperfect but it is exactly our imperfection that is our claim to the best of the human condition. We are not a sorry lot. We have one another. We are not expected to be self-sufficient. It is precisely our vulnerability that entitles us to love and guarantees us a hearing from the rest of the human race.”

In this season of need and greed remember:

You are enough.

You belong.

You are not alone.

You got people.

Violence Begets Violence

September 13, 2012I’m sure you’ve heard the aphorism, that violence never solves anything. It is a good line, one I have previously used myself. In the long view it even has some truth to it… violence often does lead to more and more complicated problems over time.

long view it even has some truth to it… violence often does lead to more and more complicated problems over time.

The problem with it is that in the short view (and most human beings live in the short view) it is demonstrably untrue. Violence can seem, for awhile, to have solved some problems rather neatly. Violence, be it the violence of a mob in Cairo or a planned strike under the cover of a mob in Benghazi… violence can seem a viable solution to a problem, even an attractive one. Why attractive? Because somehow we continue with the myth that killing people creates some kind of finality, some kind of closure, in a visceral denial that we are all interconnected and interdependent.

And yet, I’ve come to realize that there is a deeper truth about violence, one that, in my experience, comes as close to an absolute truth of anything I have ever encountered… and that is this. Violence begets more violence. When one violence is perpetrated, it created a continuing cycle that creates more and different forms of violence, spreading out in a wave from the initial point.

In fact, I wonder if there really are very many new initial points of violence, and if rather our reality is made up of a continuing harmonic of violence stretching back to the dawn of human time.

I also want to clarify what I mean by violence, for I am talking about far more than physical violence. I might strike you, which is an act of physical violence. In reaction to my striking you, you might go home and be emotionally violent to a spouse. That spouse might then tell a child that the God they learned about in Sunday School must be dead for such things to happen, perpetrating an act of religious violence on the child’s growing faith… And on, and on, and on.

We all live in these cycles and waves of many different forms of violence each and every day of our lives. It is a spiritual practice to intentionally seek to interrupt these waves of violence when they come our way. It is a spiritual practice to notice the wave, the form of violence that is perpetrated upon you, and respond with loving kindness. It is a spiritual practice to transform that violence within your spirit.

As one person doing this, the wave will likely crash around you and flow on… but as one of millions? Perhaps we can, one day, break the cycle of violence that has plagued humanity since the dawn of our awareness. Perhaps we can break the cycle in which, in this small part of this ongoing wave of violence, an Israeli-American committed an act of religious violence upon the Islamic faith, and then many enraged by that act committed these acts of physical violence upon Americans, leading us now to political calculations around another act of military violence upon Muslims.

Without such millions of people seeking to intentionally interrupt the waves of violence of all forms, we are stuck forever battered by the surf.

Yours in faith,

Rev. David

Run for Your Life!

September 4, 2012I have always been fairly athletic, and I enjoy playing a good game that gets my blood pumping. But I loathe exercise. I’ll run all day long if I’m on a court or a playing field, but ask me to run to get or stay in shape and I’ll kindly decline. I’ve tried several times in my life to become a runner, hoping to experience that “runner’s high” that I’ve heard so much about. In fact, when the running craze first hit the East Coast in the early ’70’s, I was among the first to buy a pair of bright blue Nike’s with the yellow swoosh on the side and take to the roads. I lasted about three weeks before pain and boredom overcame me. Two to three weeks seemed to be my limit every time I tried to get on the running bandwagon.

Then early this summer my daughter called and told me she had started the “Couch to 5k” program, and that I should try it too. I was skeptical, but she was persistent. “It’ll be fun,” she said. “Right,” I replied. “Like pulling fingernails is fun.” Eventually, she wore me down and I decided I’d give it a try. “C25k” (as we in the know call it) is an interval training program that starts off with lots of walking and a little running. By the end of nine weeks, you’re not walking at all, and you’re running the full 3+ miles.

I’m proud to say that I have stuck with the program and am now a “C25k” graduate, and that I’ve kept up my running since completing the program. My daughter and I have started looking for a 5K race we can enter together to celebrate our accomplishment.

But the truth is that I still find running really boring. I run a 3 mile loop around town that keeps me mostly on residential streets and a couple of busier roads. I was told that running on pavement is easier on your joints and muscles than running on the concrete sidewalks. So, when it’s not too narrow or busy, I opt to run in the road (always facing oncoming traffic as I was taught in grade school). I watch the oncoming cars carefully, to be sure that they see me and keep a safe distance. When a car gives me a wide berth, I usually give a little wave to acknowledge the driver’s awareness and kindness.

Lately, I’ve developed this little interchange between drivers and me into a kind of spiritual practice. For the past several runs, I’ve begun to say a small prayer or blessing for each passing motorist. As I wave, I say “May you know peace” or “Know that you’re loved.” I wish health, happiness, peace, love, passion, success, and joy to the occupants of the cars that pass me by. For those drivers who either aren’t watching or don’t care to give me some space, I pray for their attentiveness, their alertness, and their foresight as I hop up onto the curb.

In offering these small blessings to strangers who pass me by, I find that I, too, am blessed. As I pray for these things for others, I am reminded of the joy, peace, love, passion and successes I find in my own life. I experience the blessings of good health, of the air that I breathe in, of the incredible machine my body is. I notice the gifts of the sky, the trees, the wind and the sun.

May you know peace today. May you know that you are loved. May you feel joy. And may you find, in some small way, the opportunity to wish that for others as you go about your day.

Love,

Peter

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210

!["I am sorry" from Burning Man 2013 [by Jim Urquhart]](http://wp.patheos.com.s3.amazonaws.com/blogs/uucollective/files/2013/09/I-am-sorry-pic-from-Burning-Man-2013-by-Jim-Urquhart-300x203.jpg)