The Language of Faith

November 1, 2013

Source: Google Images Creative Commons

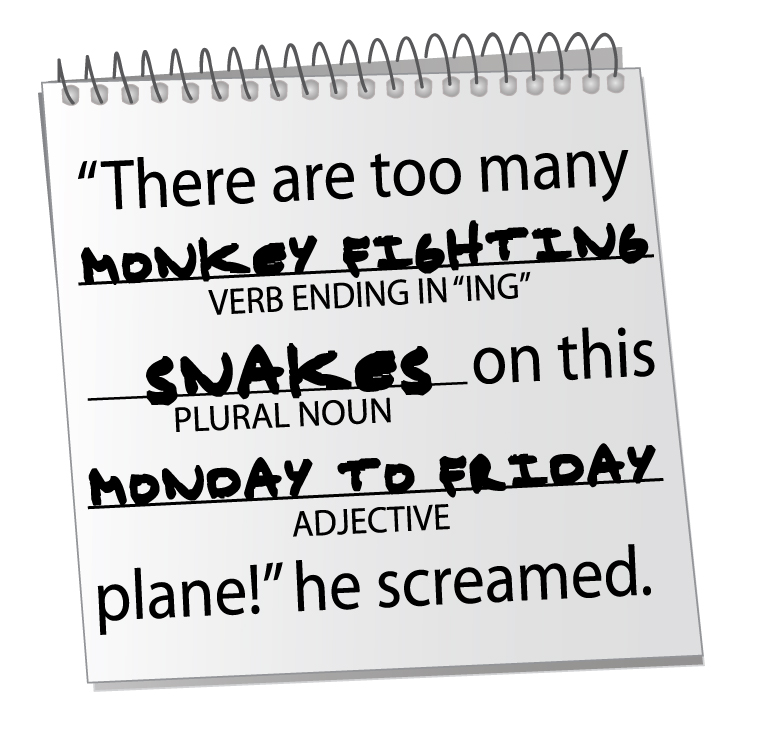

Last Sunday, while out to lunch with my husband and two young kids, we passed the time waiting for our food by playing Mad Libs. As you might remember, Mad Libs is a word game where one player asks another player to provide a particular kind of word – noun, verb, adjective, etc. – to fill in the blanks of a story. After the words are provided, randomly and without context, the other player reads the funny and often nonsensical story aloud.

If you have ever played Mad Libs, you know just how important grammar and semantics are to the art of storytelling. You also realize just how important words and context are to communication and understanding.

Words are, obviously, incredibly powerful tools. We use words to communicate, to connect, to explain, to inform, and to educate. But words have significant limitations, as well. Unfortunately, all too often words are used as a weapon instead of a tool. We use words to restrict instead of expand, to assume instead of discover.

Ironically, we often try to use language to define those things that are undefinable. We try to explain the inexplicable with rational, but overly simplistic, definitions. We fit people into our prepackaged labels –believer, nonbeliever, Christian, Jew, Muslim, atheist, humanist, idealist, pacifist, liberal, or conservative – and we try to make sense of this crazy, nonsensical, Mad Libs-like world with assumptions and categories.

But when it comes to the Big Questions, to matters of the Heart and the Spirit, there are no definitions. There are no labels. There are no prepackaged boxes.

Quite simply, language fails us when it comes to matters of the Spirit. God (I use the word “God” knowing that the word itself has its own limitations) comes in many names and is experienced in many ways. God and all things Spiritual, by their very nature, are unknowable and personal; they are felt with the heart and cannot always be adequately explained with words.

But, being the intelligent humans that we are, we try to explain that which is deeply felt with words, explanations, and sound bites. And, as a result, any inherent commonality to our human spirit gets lost, the beautiful complexity of differences gets diluted. The words – and labels – that we use become more important than the ideas.

So much division and dissention is created and exacerbated by the labels and linguistic limitations that we put on matters of faith and spiritual belief – concepts that are, quite frankly, too big to fit into any label or verbal representation.

Perhaps, we need to focus less on the words of faith and more on the language of faith. Perhaps we need to stop getting lost in the semantics of God and, instead, learn the languages of God – ones that are spoken and heard in a number of ways.

Music has always been my language of God. I love to sing (off-key) and can clumsily tap away a few songs on the piano, but I am far from what you would call “musical.” Yet music has always been a profoundly moving spiritual experience for me. Whether I’m swaying to a church choir singing “Amazing Grace,” listening to Bon Iver on my iPod, singing along to Bob Dylan in the car, or dancing like crazy with my kids in the kitchen, few things have the power to move me like music. Music creates an internal communication with the Spirit that washes my soul clean, as if I have stepped into a warm shower with the lyrics and melody rinsing away the grit and grime of everyday life.

Spiritual language can be found in any number of ways. My grandpa spoke the language of God through his generous hospitality. It was nearly impossible not to feel like THE most important person in the world when he greeted you. Others feel the language of God through the earth and nature. Gardening, for my paternal grandma, was so much more than a household chore, it was a spiritual practice unto itself. With her fingernails soiled and her hands calloused, as she tended and cultivated, she spoke a spiritual language that only her soul understood, that only her Spirit could appreciate.

Some people speak God’s language through art or poetry, photography or painting, teaching children or caring for animals, caring for the sick or sharing a meal with friends. Shauna Neiquist wrote in Bread and Wine, “When the table is full, heavy with platters, wine glasses scattered, napkins twisted and crumpled, folks askew, dessert plates scattered with crumbs and icing, candles burning low – it’s in those moments that I feel a deep sense of God’s presence and happiness. I feel honored to create a place around my table, a place for laughing and crying, for being seen and heard, for telling stories and creating memories.”

Let’s face it, we live in a chaotic world, where the unimaginable meets the incomprehensive, and devastating realities mix with everyday miracles. We want to make sense of it all. Of course, we do. In our well-intentioned, but misguided, attempts to explain, understand, and communicate, we look to definitions and labels. We rely on assumptions and suppositions, and we look to linguistic placeholders to meet the expansive scope of faith, God, and the Spirit.

We try to define the indefinable.

But maybe if we spend a little less time focusing on definitions of God and labels of faith, and instead focused on feeling the complex languages of God, maybe then we could gain a better understanding of each other and ourselves.

Naming the Ultimate, Part Two

August 22, 2013A quick peek at www.godchecker.com gives some indication of the sheer number of times humanity has attempted to name The Ultimate.

At this point philosophers–and even most theologians–have given up on a proof of god and left the battlefield. For some, a god or gods is there, for others, not so much. We can debate the existence of a god or gods, but finally all we are debating is a subjective feeling, and the argument boils down to pretty much the same thing as arguing over whether a particular dish is too salty or too sweet. It’s subjective.

So, for much of humanity, belief in a deity or deities is like a taste for boiled shrimp: some are born loving them, some are born hating them, and some acquire a taste or lose the taste along the way.

What indubitably is here, there, and everywhere, is the universe that surrounds us—the whole enchilada—“everything that is, seen and unseen,” as the Book of Common Prayer would have it.

Of this thing we can say that everywhere is the center; nowhere is the center. Of this thing we can say that it is expanding, ever faster. We can call it the universe. The multi-verse. The Whole Enchilada. Yet, ultimately, we can be assured that this everything is one big something. And it’s a huge and marvelous mystery.

This everything is One, as the Hindus and the Buddhists would have it. This everything is The Way, as the Taoists would term it. Remember those words from the Ashtavakra Gita:

One believes in existence;

Another says, “There is nothing!”

Rare is the one who believes in neither.

That one is free from confusion.

This wholeness, in all its mystery and contradiction, has been a tough thing to grasp for the Western brain. Though the idea of the oneness and wholeness of all existence is at least six thousand years old in Hindu thought, we Westerners have built our cosmology and our language around polarities such as black and white, up and down, in and out, I and other, existence and non-existence, secular and religious.

In the West, the earth sat on pillars; had corners; and heaven was up there, hell down there. Our spirits went to those places. Our gods and demons lived in those places.

It’s not easy to get outside those understandings. Often we can’t, except by logic, with some anti-logic thrown in, and hard work. Or in those rare, amazing mystical moments when all feels like one and everything is A-OK. In our everyday lives, the earth sits, rock solid, and the sun and moon go up and down.

Yet none of this is “true.” We Westerners often think that thought is the only way to truth. And it is, for some forms of truth. Yet that sort of truth leads us to being “lost in our forehead,” as Hindus put it. “All up in our head.”

We can enter the space of oneness only by thought, then the letting go of thought. Why do something so foreign? Hang on. I hope to show you why . . .

Naming the Ultimate, Part One

August 15, 2013I suspect that we think about the ultimate because we can’t manage to see ourselves as ultimate. Or infinite. Or eternal. Or all-knowing. And that hurts! It hurts to be a too, too solid, limited, fragile creature.

So, we think about the Spirit of Life. God. The gods. The Ultimate Concern.

Search the internet for the names of God. Besides the ninety-nine that Sufis chant, just start with “A” and work through time and geography. Or read Neil Gaiman’s novel American Gods. I’ll bet you don’t know them all! Furthermore, you probably only believe in one or two or five at the most.

Always, human beings have pinned names on the absolute.

We call those who do not believe in the gods not a word of their own choosing but “a-theist.” Everyone is defined by the naming of the ultimate. We human beings take this quite seriously.

Alan Watts called this ultimate thing, “the which of which there is no whicher.” That about sums up the idea, doesn’t it?

Inevitably, with the naming comes the assignment of attributes: “Omnipotent.” “Omnipresent.” “Omniscient.” I learned to chant these long, hard words as a child in Sunday school. It’s what God was— Everything. Everywhere. All the time . . .

Walking to school? Yes! In the bathroom? Yes! Watching dad working at the factory? Yes!

The thought was reassuring. And frightening. And threatening. This was the Big Guy in the Sky, who had walloped the world in a flood and made Noah a sailor. The Big Guy who waxed the Egyptian kids and drowned—again with the drowning!—hard-hearted Pharaoh’s army.

This was the Big Guy who would wipe out the world with fire next time. And He really, really didn’t like human nature.

“But wait!” I said. “What about . . .” And so it went, ‘round and ‘round in my little primate brain. I was wrestling with the which of which . . .

Naming the ultimate. Assigning attributes to the absolute.

“The which of which there is no whicher.”

Always this ultimate was about what we—poor farmers in the Midwestern United States—weren’t. And this exhausts at least one avenue of inquiry: we limited creatures want some “whicher” out there that keeps an eye on the (clearly dangerous) machinery of the universe.

But then my little primate brain realized just how blatant a case of wish-fulfillment this was. And so off I went, searching for another “which.” About that . . . next week.

Acts of God

May 21, 2013People are dead, including children. Whole neighborhoods are utterly destroyed, brought down to foundations and rubble. People are injured, traumatized, bereft. And there is no one to blame. No bomber, no shooter, no mad man or terrorist. Simply an “act of God.”

How I hate that phrase, act of God. As if God would come down from the clouds to smite a town out of, what, spite? Vengeance? God does not cause weather events, not out of a need to punish infidels and homosexuals, and not because he needed to call his children home to be with him. You will not find God in the great wind, any more than Elijah did.

No, you will find God in the people who keep calling to find out if their friends and neighbors are OK, in the parents who struggle to assure their children that they are safe, in those who sit at the side of those who mourn, in the mourners themselves. God is in the search and rescue dogs who are tirelessly moving house by house, searching for the scent of the missing, and in their tired handlers who volunteered and trained for this expert, grueling work. God is in the hospital staff tending the wounded and in the family members who wait and wait, hoping their loved one will be OK. God is in the first responders who are still hoping to find children alive and for those who have to carry still figures from the wreckage. God is in the people around the world sending their prayers and their love out to people they will never meet and the people who send their money to the Red Cross or animal rescue groups because it’s the only way they can think of to help.

And yes, God is in the people who dare to point out that while any given weather event is just weather, however tragic, a pattern of more and more extreme weather—the droughts, heat, hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, one after the other—that pattern is not an act of God. That pattern is predicted by scientists who study climate change. Which is not an act of God. It is the consequence of a string of human choices. God is not in the droughts and the floods and the tornadoes. God is in the scientists who keep telling the truth when it seems no one is paying attention. God is in the all the people who are trying to limit their use of fossil fuels, in the companies and schools and churches who have invested in solar panels, in the environmental groups calling for meaningful legislation.

God is not in the wind. God is in all the people who see the suffering that is, and the suffering to come, and who choose compassion and justice and the hope of a better world.

A God We Can Believe In

February 1, 2013Podcast: Download (11.7MB)

Subscribe: More

At home on a bookshelf we have a massive folio-style slipcover book titled Cabinet of Natural Curiosities by Albertus Seba, a pharmacist in eighteenth-century Amsterdam. In 1731, after decades of collecting strange and exotic plants, snakes, frogs, crocodiles, shellfish, corals, insects and butterflies, as well as a few fantastic beasts, such as a hydra and a dragon, Seba published an illustrated catalog of these curiosities. It’s an amazing display of biodiversity—enough to make anyone curious about why things change and how the same species can vary so much from one specimen to another.

At home on a bookshelf we have a massive folio-style slipcover book titled Cabinet of Natural Curiosities by Albertus Seba, a pharmacist in eighteenth-century Amsterdam. In 1731, after decades of collecting strange and exotic plants, snakes, frogs, crocodiles, shellfish, corals, insects and butterflies, as well as a few fantastic beasts, such as a hydra and a dragon, Seba published an illustrated catalog of these curiosities. It’s an amazing display of biodiversity—enough to make anyone curious about why things change and how the same species can vary so much from one specimen to another.

People Ask About God (Excerpt)

February 1, 2013Podcast: Download (3.9MB)

Subscribe: More

People go astray in their search for God because they do not take the right starting-point. We should never begin by asking, “Is there a God?”—as though God could be something outside of ordinary experience; or, to put it in the old-fashioned way, something outside of Nature. Read more →

If I Were Asked

February 1, 2013Podcast: Download (2.1MB)

Subscribe: More

If I were asked to confess my faith or my beliefs out loud, and I were scrambling for some place to begin, I would start in the desert, in the lonesome valley, and say that first of all and ultimately we are alone. No god abides with us, caring, watching, mindful of our going out and coming in. The only certainty is chance connections, both chosen and involuntary, that matter most of all and ultimately help and heal and hold us.

Sun/God

February 1, 2013Podcast: Download (1.3MB)

Subscribe: More

Your missionary ancestors told Indian people that they were worshipping a false god when we prayed to the sun. The sun is the most powerful physical presence in our lives. Without it we could not live and our world would perish. Yet our reverence for it, our awe, was considered idolatry.

A Prayer

February 1, 2013Reflections on God

February 1, 2013Podcast: Download (6.2MB)

Subscribe: More

We asked each of our ministerial interns to share a reflection on what God means to them. Here’s what they had to say. Read more →

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Latest Spiritual Reflection Posts

Latest Quest Monthlies

Weekly newsletter

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.