When did Unitarians begin?

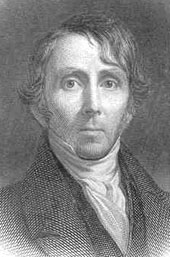

September 1, 2016There are different ways that you could define the beginning of Unitarianism. But many people would say that Unitarians were first defined as a distinct religious movement by William Ellery Channing, in a sermon given in 1819.

In this sermon, called “Unitarian Christianity” (or sometimes “The Baltimore Sermon,” because he gave it at an ordination in Baltimore), Channing laid out what he though were the particular beliefs of the group of liberal Christians who were sometimes referred to as “Unitarians.”

Unitarians, he said, did not believe in the trinity of God the Father, God the Son (Christ) and the Holy Ghost—which is what gave the group the name Unitarian, for the unity of God. But more than that, he described Unitarians as believing in human goodness, and believing in the importance of using reason in looking at religion.

Channing said that thinking is one of the most important gifts that we are given as human beings, and that surely God expected us to to use our gifts of reason in understanding religion as well as the rest of life.

In 1825, just six years later, the American Unitarian Association became the official organization of the Unitarians.

Moving Toward Freedom

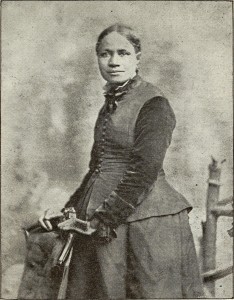

March 31, 2016Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was born a free Black woman in Baltimore, Maryland in 1825. She was raised in the household of her uncle, an educator and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) minister. He was also an abolitionist—a person who objected to the enslavement of blacks. Harper became an educator and abolitionist as well. She also became a writer, publishing her first book of poetry at twenty and later in life publishing the first short story by an African American woman. Her writing often urged Blacks, women, and people in oppressed groups to take a firm stand for equality and freedom.

In 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was passed. It became dangerous to be a free Black in Maryland because slave owners could claim Black people were runaway slaves and force them into slavery. So, Harper moved farther north to Ohio and then to Philadelphia. She taught, ran part of the Underground Railroad helping slaves escape to freedom, and lectured around the country.

In 1863, abolitionists celebrated success with the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the slaves. But there was a long road ahead to full equality, and Harper spent the rest of her life working for women as well as African Americans to have access to full freedom and justice.

To read some of Harper’s poems click here.

A Woman of Courage: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

March 19, 2015In the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the year 1858, a young woman entered a streetcar and sat down. The conductor came to her and insisted she leave, but she stayed quietly in her seat. A passenger intervened, asking if the woman in question might be permitted to sit in a corner. She did not move. When she reached her destination, the woman got up and tried to pay the fare, but the conductor refused to take her money. She threw it down on the floor and left.

What was that all about? Read more →

Living History: How JFK’s assassination woke me up

November 19, 2013I was sitting in a small desk, and Mrs. Graham was at the front of Room 3 in Overbrook School in Charleston, West Virginia, the day that John F. Kennedy was shot. Randall Hainey’s mom came running in the side door with a transistor radio to tell us.

Handing out lined paper, Mrs. Graham said solemnly, “You will remember this day always. Write down exactly what happened, because you’ll want to tell your grandchildren about it. You are part of history.”

I remember sitting there in disbelief. Someone could shoot the President? I was part of history? Mrs. Hainey and her transistor radio would matter to my grandchildren? I might have grandchildren? Mrs. Graham believed in us, not just as children, but as life itself, as part of the living movement of history. (She remains my favorite teacher ever, all these years later.)

For me, just two days into my eighth year on the planet, it was all a jumble. I could see that my parents, the only Kennedy supporters in our Republican neighborhood, were unraveled.

JFK was the last president who I saw simply and completely through the loving eyes of a kid, a President with kids of his own about the ages of me and my younger brother, whose wife wore clothes that my own mother admired. I’m too young to have had the kind of adoration that my older siblings did—adoration fused in knowledge of any issues or policies that Kennedy might have supported or opposed. I knew The President as The Most Important Man in the World, whose very existence was in some way undifferentiated in my mind from that of Superman or Julius Caesar or Santa Claus.

In the hours and days following his assassination, I remember watching my mother, sitting quietly on the floor, playing with my dolls but riveted by her emotion, while she ironed and watched our black and white TV incessantly. I remember her telling the story, over and over, as if trying to believe it herself, the story of seeing Lee Harvey Oswald get shot on live TV.

My mother, a West Virginia activist, had been quite involved in the JFK campaign. Hubert Humphrey’s brother had been slated to speak at our small Unitarian fellowship in early 1960. He was sick, his brother Hubert was in town, so Hubert covered for him. My mother then leveraged this to call the Kennedy campaign and say, “Humphrey came, so you should, too.” Readers who follow history will recall that West Virginia was critical in this election. So, lo and behold, Kennedy came, and my mother was central in his coming—though he spoke in a much larger venue than our tiny congregational building. (I’m too young to remember any of this. My mother told it to me years later, and my older brother got to shake his hand!)

What’s the point of this blog? I guess, as we spend the week inundated with stories of what happened and what might have been, stories of JFK as larger than life as either Sinner or Saint, what is most interesting to me is the small stories. The stories of how his life and his death woke up people of all ages to our own place in history. If there is anything I want to learn at this fiftieth anniversary, it’s not more details about Jackie’s blood spattered dress. It’s about how ordinary people can claim our lives and our power as being the stuff of life itself. It’s all the tiny ways in which a stunned nation moved forward together, grieved and recovered and made sense of the insensible, whether at elementary school desks, in corridors of power, or over ironing boards. Those lessons—of stepping up, living through, making sense and caring for one another, matter every day.

Mrs. Graham’s words, “You are part of history,” woke me up. They rang like a bell. They were heard by some tiny, incredulous part of me that said, Really? I am a part of all this? I will exist beyond recesses and piano recitals, I will remember this as I create my own adult life? And so it has been. From teachers such as Mrs. Graham, and my mother, and yes, from watching a dignified widow and her children standing in a strange cemetery, I came to understand myself as having a role to play, a role that could matter. Whether we were born in 1963 or not, may this anniversary wake us up to that fact.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210