A Creative Life

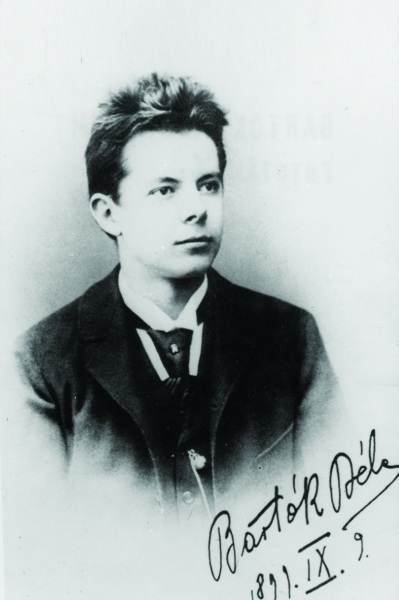

April 7, 2017Béla Bartók was a Hungarian pianist and composer who added a great deal to our world through his creativity. He started playing piano as a tiny child, and knew 40 songs by the time he was four—and gave his first public recital , including an original composition he’d written two year earlier, when he was eleven.

Bartók went on to become a famous composer who not only wrote his own music, but also went out around the countryside gathering folk music, which he often worked into his compositions. While he was collecting music from the Székely people in Transylvania he learned about Unitarianism.

He liked the idea of a creative religion that was less about following rules and more about connecting with all aspects of life. He eventually joined a Unitarian church in Hungary, and attended with his son.

With the rise of a fascist government in Hungary and the approach of the Second World War, Bartók fled to the United States. He was safe there, but felt lonely and disconnected from his homeland, and it was hard for him to continue to write music. But when he was diagnosed with leukemia and knew that he did not have very long to live, his creative energy returned in a burst and his last compositions are often considered his greatest.

To learn more about Bartók and listen to some of his music, visit the NPR story, “Béla Bartók: Finding a Voice Through Folk Music”

Music: Béla – Evening in the village

Here is one of Bartók’s compositions, titled “Evening in the Village.” The tune comes from a folksong, which is called the “ancient Székely anthem.” The pictures in the video were almost all taken in Transylvania, where Bartók discovered Unitarianism. (The one with the gate was taken in Máriabesnyő, a famous shrine in the outskirts of Budapest.)

Who’s In and Who’s Out of Institutions (and the immigrants between)

September 12, 2013The British social anthropologist Mary Douglas had this to say about institutions:

Inside a religious body you get sects and hierarchies, inside an information network you get bazaars and cathedrals, it is the same, call them what you like. They survive by pointing the finger of blame at each other.

That about sums it up, doesn’t it?

Douglas is most famous for her theory of dirt: She claimed that human groups form solidarity by what we consider disgusting. For example, if your group considers eating sheep’s eyes disgusting, you’re unlikely to become very intimate with the group next door that considers sheep’s eyes a delicacy.

Douglas claims that human groups, or “institutions,” allow those inside the institution to point fingers at those outside the institution. As we stand inside and point fingers, we develop group cohesion: there’s an inside and an outside.

But, it doesn’t stop there.

Douglas thought that first we off-load responsibility for our actions onto an institution, then we begin to allow the institution to think for us. As a matter of fact, Douglas believed that our institutions operate exactly opposite from the way we generally think they do: we think institutions make small, rote decisions for us; but, actually, we allow institutions to do the big thinking for us, and we stick to the small stuff (–you know, such as consuming too many calories and avoiding exercise. Stuff like that.)

Because . . . it’s not easy bearing personal responsibility for the things that institutions such as government do. Yet, if we intend to lead an examined life, we must look in the mirror and ask ourselves what benefits we get from those things we off-load onto institutions.

Let’s think about government . . . oh, say, the United States government: bad immigration policy; institutionalized racism; millions of working poor; gun “freedom” that kills thousands per year, and poorly regulated industry, to name a few problems. Now, ask yourself, What benefits do I get by being in that group?

It’s disturbing.

It’s disturbing because Dr. Douglas is not saying, human beings form institutions and then wag their fingers at outsiders when they aren’t thinking about it or when we get lazy or when we fail to change wrongs. She isn’t saying those other people do that. She’s saying that’s what ALL institutions do. It’s disturbing because a basic fact of human nature is that we form groups, then we lose any ability to act morally concerning those things we have given away to an institution. Then we benefit from the immoral actions.

Now, you can say, “Oh, well, she’s just a crazy leftist feminist postmodernist, so, you know how THEY are!”

Or we can say, “hmm, that’s interesting! How can we use that human propensity both to better understand institutions that we don’t like, and those we do?

How can we use that idea to create institutions that encourage the sort of human action that we see as positive, rather than the sort that we see as negative?

I know you’re already way ahead of me on this . . . ideally, Unitarian Universalist congregations are places where people are not only encouraged, but required to question assumptions. Places where we encourage finger-pointing at systemic injustices, not at the people who may or may not be perpetrating the injustices, for whatever reasons . . .

If we look at Mary Douglas’s ideas from this perspective, they aren’t quite as crazy. Or quite as ivory tower!

Take, for example, immigration.

Consider for a moment that, as nations go, Mexico is not a a poor one. As nations go, the average Mexican is somewhere in the mid-range of income and social well-being for human beings on the planet. It isn’t that Mexico is poor, by international standards, but rather that the income disparity between Mexicans and North Americans is large–as a matter of fact, the disparity is the largest of any two bordering nations on earth.

That goes a long way toward explaining why people might consider crossing a border. To me, anyway, it’s hard to point my finger at a group of people trying to do that.

How have we–and let’s listen to Mary Douglas and include all of us–how have WE—the institution called the USA–responded to the immigration issue? Rather than facilitating the flow of people back and forth across the border, we have tried to stop the flow–we are still following that policy.

Now, I’m old enough to remember when the border was porous. People came here for summer work, then went back to Mexico–they went back home–for the winter. People can’t do that anymore. Because we have spent billions of dollars to stop them. They’re stuck here.

What would you do, if you found yourself stuck in a foreign country, no way out?

First you would go to the embassy, right?

Then you would start calling on your support network . . . family and friends.

Then you would get out your credit cards . . . see if throwing money around might help . . .

What if your loved ones were across the border?

How long would it take before you just took off walking . . . ?

I have a challenge for you: listen to Mary Douglas and get outside your comfort zone. Call yourself on one of your prejudices . . . . Call your own bluff on one of the “institutions” where you sit comfortably and point fingers from . . .

Maybe it’s the institution called race. Maybe it’s the institution called social class. Perhaps it’s the institution called education. Perhaps you wag your finger at close-minded people.

Whatever.

Try reminding yourself this week that, as psychologist Steven Pinker puts it,

“Our minds are organs (like the lungs), not pipelines to the truth.”

Our minds are organs, not pipelines to the truth.

Try it. Actually realize that your brain is an evolved organ and has its limitations. And your brain is NOT an institution.

This week, call yourself on one of your prejudices. Call yourself on one of the things you get away with because of an institution you belong to. Step outside your comfort zone. Actually listen to someone who your prejudice tells you can’t have ANYTHING valuable to say.

Instead of pointing a finger and even wagging it a little, sit back and listen.

Try it.

They Walk Into the Place Where (a reflection on immigration)

June 20, 2013They walk into the place

carrying a bandana,

carrying a balaclava,

carrying a bordada

made by abuela.

They walk into the place

that burns the soles of huaraches,

the soles of tennis shoes

into twisted rubber.

They walk into the place

carrying an extra tee shirt.

An extra dress for a hija.

They walk into the land

carrying cheese crackers

and Red Bull and cheap cell phones.

They walk into the place

where money is god.

They walk into the place

where violence is all.

They walk into the

North American desert,

the border boondoggle,

the land of prisons for profit.

The walk into the land of

“you don’t understand.”

They walk into the land

where violence is the export.

They walk into the land where

loss the rule of the land.

http://www.tucsonsamaritans.org

We Do Not Fear People Whose Stories We Know…

October 22, 2012Back before the Twin Towers fell and the Pentagon was attacked by plane, before there was a US Department of Homeland Security, way back when ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) was known as the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service,) – a lifetime ago and yet still less than fifteen years have passed – I served as a Legal Tech for an immigration law firm in Washington, DC. I was a twenty-something white woman, with southern working class roots and a damned fine Midwestern liberal arts college education, figuring out if I wanted to go to law school.

In addition to filing forms at the law firm, I was a narrative gatekeeper. In search of asylum, an HIV-waiver, a work visa? Sit down in that chair and tell your story to me, in all its intimate and gory details. My job was to take your story and craft a narrative that would compel government officials to consider your case favorably (or at all, in some cases).

It was extraordinary work. I met families from Iran, the Philippines, Malaysia, El Salvador, Nicaragua, the United Kingdom, Sri Lanka – from all over the world. Each had an extraordinary story – some that were exciting, some that made my stomach turn, some that broke my heart open. After just a few months of working with the firm, I added Tums® to my requested office supply list and I went through them by the bottle.

I was angry that any human being had to share the excruciating details of their torture and their trauma to a recent college graduate and pray that she told their story well enough for an officer or a judge to grant them grace. I was angry at how much harm was inflicted by my country on people who had already suffered much harm in their country. Soon I figured out that I did not want to grow up to be a lawyer. I did not want to risk growing immune to the power of these stories or becoming complicit in the process. What I wanted to do was work for systems change.

Many years later down the winding road of my life, I found myself standing in an ICE office for hours. I was bonding an immigrant – the friend of a friend of a friend, ripped away from his family and hauled out to detention in rural Louisiana.

Memories of dozens of stories from the cases I had worked on flooded over me as I waited in the reception space during the long stretches between each step of the ICE process.

I remembered the proud father terrified that his extremely Westernized daughter would be stoned to death if deport to their home country.

I remembered the gay man who had seen his friends killed for daring to hold hands and who had fled his homeland in fear of his own life.

I remembered the woman raped by an elder of her church and denied the letter of good standing that would have allowed her to become a citizen.

I remembered the sweet faced Latino youth who was infected with HIV while in detention in the US and then denied status because he was HIV-positive.

I remembered their stories and the stories of so many others who struggled to create a better life for themselves and their families here in these United States.

Because I know their stories, immigration will always be a moral issue for me. Because I know their stories, I will not buy into the dehumanizing stereotypes being peddled to me and my fellow patriots. Because I know their stories, I will stand – in an ICE office, in the pulpit, in the voting booth, in the interwebs – on the side of love. I invite you to stand on the side of love, too.

The New Face of Courage

June 26, 2012Courage comes in many forms and it wears many faces. We often think of those who put themselves in harms’ way for the sake of others as being courageous. The firefighter who rushes into a burning building. The soldier who risks life and limb to save a buddy who’s been wounded. The mother who shields her baby from imminent danger.

This past week, I saw another face of courage. It was worn by a young woman who lives in Arizona, whose mother brought her across the border when she was an infant. All her life she lived in fear. In fear of the knock on the door in the middle of the night. In fear of the police who patrol her neighborhood. In fear that when she came home from school her mother would be gone, taken to a detention center to be deported.

This young woman, now in her twenties, has declared her freedom from fear and has become an advocate for the rights of undocumented people just like herself. She has attended and spoken out at immigrant rights’ rallies. She has “bucked the system” and achieved both a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree from Arizona State. She has started a “language exchange” in Phoenix, where undocumented youth from her community can come and teach Spanish, thereby earning a little cash to support themselves while they also learn to speak English from their students. (See the video here: Spanish for Social Justice ) She is, in all aspects of her life, proclaiming her heritage, her identity and her status in the face of frightening, brutal and repressive forces. And she’s doing it with joy and love. The face of courage that I encountered last week wears a big smile, and it is beautiful.

After hearing this woman’s story, I’m called to ask myself where courage comes from. Not the “run into a burning building” courage (which, while certainly admirable, often is more a reaction to circumstance), but the kind that says “I’m in this for the long haul, no matter what.” The kind of courage that enables and empowers us to get out of bed, day after day, to face a world full of risk and danger. I have to believe that this kind of courage is grounded in love. In the love that we receive from others and in the love we have for the world.

We need a community of love around us to provide the foundation for all that we do. Knowing that we are loved, no matter what, by our family and our friends gives us the courage to venture out into a hostile world. It also forms the basis of our self-esteem, the basis of our belief that our lives matter and that we can make a difference. This kind of love empowers us to declare our own worth in the face of those who would deny it.

A love of the world calls us to engage with it, in all its beauty and all its horror. When we love the world, like a parent with a troublesome child, we acknowledge its imperfections, yet we cast our gaze to the horizon of its potential. Love for the world allows us, in the words of Bobby Kennedy, “to dream things that never were, and say, why not?” And it creates in us the commitment to do what we can to make those dreams a reality.

As I move through the days ahead, I will carry the image of this young woman with me. She is, for me, the new face of courage.

Peace,

Peter

Fear and Love at Tent City

June 24, 2012

There is a protest at Tent City tonight, the place where Sherriff Joe Arpaio holds thousands of immigrants in his self described ‘concentration camp.’ Where there is never any relief from the Arizona heat, where humiliation is a daily occurrence.

I’m with my people, in our bright yellow Standing on The Side of Love shirts that match the school buses that take us there, Unitarian Universalists in Phoenix for our annual convention. There are hundreds of us going, a couple of thousand maybe, mostly white, middle class, documented. And yet I am afraid.

I’m afraid because I’ve heard there will be counter-protestors, militia folks maybe, perhaps with the weapons which are legal to carry in Arizona. I’m afraid because it’s so hot, because I’m not exactly Olympics material in my physical fitness, because I am taking a teenaged child whose safety means everything to me.

And then, as we sit in worship and prayer, preparing to go, speakers from the local Latino community speak. A young woman describes her decision to commit civil disobedience, to be arrested by Sherriff Joe Arpaio, because she is tired of living in fear, of her whole community living in daily fear of being rounded up for real or imagined infractions and thrown into the Tent City, as they have been for the past 20 years. A young man describes arriving in the United States at age one, and now facing deportation –leaving the only country he’s ever known to be sent to one which is foreign to him.

And I begin to feel embarrassed by my fear. Not ashamed, not guilty, just embarrassed. As if I am a kid who grabbed too many cookies off the plate. And I think, this fear that binds us all, this fear of being arrested and humiliated and tortured in our own country: How does that hold us back? How does that diminish us? The young woman who chose to be arrested says, Yes, she was afraid, but she’s been afraid all her life. This arrest, in a way, freed her. I think of the words of the poet Audre Lorde, in her essay which is desert-island-essential to me, The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action:

What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?

As we get into our bright yellow school bus, a minister offers a prayer for our journey. I say to the driver, Are we holding our departure up because we are standing up praying? And she looks up with some annoyance and says, “No! I am praying!” As I begin to lead the crowd off the bus, she says, “Thank you so much for doing this. My husband is in there.”

At Tent City, I don’t see any counter protestors, with or without weapons. I see a small gaggle of brave locals, who have come to thank us for being there. One woman I speak with tells me that her inability to pay for a traffic infraction landed her there for ten days. She describes the endless heat, the lack of adequate drinking water, the horrible food. She says then, tears in her eyes, “My girlfriend is in for a year.”

Another man holds a sign charging Joe Arpaio with homicide. I ask him how many people have died at Tent City. He says at least five. I ask him if his church stands up to speak out about this. He replies sadly, “I am still Catholic but I do not go to church anymore. Most of us don’t. There was one priest who spoke out for us but they got rid of him.”

As I get back on the bus to go back to air conditioned comfort, a shower and clean pajamas, his words stay with me most. I wish that I could have responded, in Arizona or in my own home state of Minnesota, “You would be welcome in my church!” I know that the Phoenix UU church is doing fantastic work to be welcoming, to stand tall as an advocate for justice for immigrants. And yet I know that, while we stand on the side of love, sometimes we stand too far off to the side, in our fear, in our privilege, buffered, unwilling to disrupt our comfort. I offer a silent prayer and wake up this morning with his words still piercing my heart.

(Photos by Jie Wronski-Riley)

Renew Your Membership

We invite you to join your fellow CLFers to renew your CLF membership and stewardship of the CLF for another year.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210