Did You Know?

May 1, 2016Podcast: Download (Duration: 0:27 — 632.2KB)

Subscribe: More

…that the CLF offers a variety of online classes? Check it out here. Read more →

Breathe

May 1, 2016Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:02 — 974.4KB)

Subscribe: More

How can I breathe at a time like this,

when the air is full of the smoke

of burning tires, burning lives? Read more →

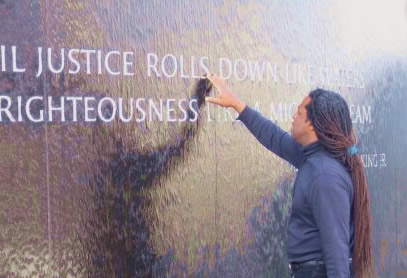

Justice

May 1, 2016May 2016

It is justice, not charity that is wanting in the world. —Mary Wollstonecraft

Articles

Calling Forth Justice

Arif MamdaniHow many of you have a decent relationship with the Bible —as in, you’ve had at least a couple of conversations and neither of you left angry? Read more »

Anger and Justice

Rev. Audette FulbrightThe only word repeated more than once in our seven UU principles is the word “justice.” We are called to justice. Read more »

A Public Voice for Justice

Quest for MeaningAt the CLF we strive to be a public voice for justice and to curate a conversation that leads to deeper understanding of how we can build a more just world. Read more »

Justice Behind Bars

Quest for MeaningThree of our CLF prisoner members wrote pieces for Quest Monthly on the theme of Justice. What follows are excerpts from these pieces. Read more »

From Your Minister

Rev. Meg RileyWhen it comes to justice-makers on the front lines, one group of people often shows up—mothers. And when mothers truly know that, as the saying goes, “there’s no such thing as other people’s children,” I believe we have the power to accomplish anything. Read more »

REsources for Living

Rev. Dr. Lynn UngarIn her column, Rev. Meg talks about how mothers have a special urge toward justice, born out of a fierce love for their children that demands a world where those children—all children—can be safe and respected. Read more »

Breathe

Rev. Dr. Lynn UngarBreathe, said the wind. How can I breathe at a time like this, when the air is full of the smoke of burning tires, burning lives? Read more »

Justice

Quest for Meaning“It is justice, not charity that is wanting in the world.” —Mary Wollstonecraft Read more »

A House for All

February 1, 2016You could argue whether Jane Addams was a Unitarian, since she regularly went to a Unitarian church, but never joined. But you can’t argue about whether she understood the true meaning of hospitality.

Jane grew up in a wealthy family, but when she discovered as a child that many poor people in the cities lived in terrible conditions, she wanted to make a difference. In 1889 she and Ellen Starr founded Hull House, a big house in Chicago which offered a place for the many poor recent immigrants in the city to take part in clubs, discussions, and activities, as we ll as take English and citizenship classes, and enjoy theater, music, and art classes.

About 25 people actually lived at Hull House, and Jane made sure that both wealthier people and poor immigrants lived there together, since she believed that people with different experiences could learn a lot from each other. Jane Addams and the other women who ran Hull House with her created an amazing space of hospitality where people could learn, grow and have fun together. In 1931 she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Learning More Online:

To learn more about Hull House, and the visionary women who founded it, visit the National Women’s History Museum website. The Jane Addams-Hull House Museum today serves as a living legacy to Jane Addams and her vision of hospitality for all; learn more about their ongoing work at hullhousemuseum.org

Seeing is Believing

December 12, 2014In the wake of Ferguson, in the wake of Trayvon Martin and Oscar Grant and the 12-year-old boy with a pellet gun who was recently shot by a police officer in Cleveland and all the other young Black men killed because a White man found them threatening, it’s hard to know what to say. It’s hard to know what to say to my Black teenage daughter as we take the long way home from downtown Oakland to avoid protests that have started to turn violent. It’s hard to know what to say to Black friends who are grieving publicly on Facebook, who feel assaulted once again by a system which has betrayed them over and over. And it’s hard to know what to say to a good, kind-hearted White friend who feels that her police officer son is being defamed by complaints against the police, and says that we all experience racism, and that we should just all be nice to one another.

kind-hearted White friend who feels that her police officer son is being defamed by complaints against the police, and says that we all experience racism, and that we should just all be nice to one another.

It’s hard to know what to say, and it’s hard not be impatient with people who seem hopelessly out of touch. I have to start by remembering that we all speak from what we know, what we experience, what we see. We speak as eye-witnesses to our own lives. Which means that for a lot of White people, racism doesn’t really exist, or exists only as a few isolated instances. After all, what most of us who are White see in our daily lives is that the police are there to keep us safe. What we see is that our walking down the street or driving a car is not a subject for police investigation. What we see is that the folks who turn to look at us in stores are wondering if we need help. That’s reality.

And if that’s your reality then rage against the police seems misplaced, unreasonable, unjustified. If the justice system has always looked to you like, well, justice, then protesters on the streets are threats to the public safety, not advocates pushing for public safety. We know what we see. Who we imagine the public to be are the people who look or dress or talk like us.

I suspect that everyone who drives has been in the position of wanting to tell off the idiot who has come to a complete stop in the middle of the street in front of us. Maybe we honk our horn, or just sit there grumbling about the rude, clueless twit blocking our way for no reason—until we finally see the pedestrian crossing past the vehicle that was blocking our view. It turns out that the driver in front of us could see something that we couldn’t, was acting on information that we didn’t have.

It isn’t easy. The folks with the privilege have every habit of assuming what they see is the “real world,” and every incentive to stay in that comfortable world. The tricky part is that it’s really the job of the White people to help other White people see around the corner. There are many terrific books and blog posts and articles by people of color about their experiences, and White folks would do well to read them. But ultimately it is the responsibility of the White people who’ve caught a glimpse of the pedestrian in the road to help other White people see what is beyond their field of vision. Even when it’s uncomfortable. Even when you don’t quite know how to do it. Even when you’re pointing toward something that’s not altogether clear to you.

Maybe it’s enough to just ask everyone to enter the conversation aware that the fact that you don’t see something doesn’t mean it isn’t there.

A Whole Heart: Remembering Pete Seeger

January 29, 2014 For the last couple of days my Facebook feed has been full of tributes to the late, great Pete Seeger—as well it should be. A genuinely remarkable man, Seeger spent his long life seeking justice, fighting oppression, telling the truth as he understood it, even in situations where the truth was most unwelcome. (If you haven’t seen the transcript of when he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, do yourself a favor and read it.) He stood in front of the crowds to protest war, and he sailed up and down the Hudson River fighting pollution. But more than that, he had a gift for bringing people together, for turning a crowd into a community through the power of song.

For the last couple of days my Facebook feed has been full of tributes to the late, great Pete Seeger—as well it should be. A genuinely remarkable man, Seeger spent his long life seeking justice, fighting oppression, telling the truth as he understood it, even in situations where the truth was most unwelcome. (If you haven’t seen the transcript of when he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, do yourself a favor and read it.) He stood in front of the crowds to protest war, and he sailed up and down the Hudson River fighting pollution. But more than that, he had a gift for bringing people together, for turning a crowd into a community through the power of song.

He was extraordinary, but here’s what strikes me. Anybody who really wanted to could do what he did. Sure, he was a good musician, but there are lots of people with better voices—walk into any college conservatory in the country and you’ll find a singer with a rounder tone, a more operatic sound. Sure, he was good on the guitar and the banjo, but there are people in my personal acquaintance who are better. He wrote some wonderful songs, but they’re hardly models of musical sophistication. His talent was considerable, but not really anything amazing—maybe not even all that special.

What was so incredible about Pete Seeger was not any singular gift or talent. What we celebrate, what we remember, was not a man who could do things no other person could, but rather a man who spent his whole very long life walking with a whole heart toward what he believed in. Whether it was his 70-year relationship with his beloved wife Toshi or an afternoon’s connection with a crowd at a concert or a protest, Pete was fully present, fully engaged, ready to be connected. He was a man who knew the power of the people, and who used the considerable force of his personality not to draw attention to himself, but rather to engage people with each other, and with their ability to create positive change. He gave himself, and he kept giving—not as a martyr, but as someone who found great joy in the giving.

He had, in short, the power of the music. Not the power of musicianship; not the prodigy talents of a Mozart or a Yo-Yo Ma. No, Pete Seeger had the power of living in his music, living through his music. He knew the power of music to tell truths in ways that people could hear them. He knew the power of music to draw folks together through the interweaving of voices. He understood the power of music to raise energy, to call forth energy, to move people forward. He sang, and invited people to sing with him, because he understood the deep connection between music and love, and between love and justice.

And he just kept on doing it, decade after decade. We’ve lost a unique spirit this week, a man who put his whole heart into everything he did, a man who had a whole heart, unbroken by cynicism or despair. But I think what he would want us to know is that any of us could do what he did. Any of us could stand up to injustice, work for peace, speak our truth, sing out and keep singing. Any of us could be an instrument of freedom, of joy, of connection and the power of the gathered will of the people. Any of us could. Pete Seeger did.

The Real War on Christmas

December 11, 2013I confess it all seems a bit silly to me, this whole notion of there being a “war on Christmas” because some institutions are wishing people “Happy Holidays” rather than “Merry Christmas.” Does it really matter? OK, I admit that I, personally, am annoyed with the signs that declare that Jesus is the Reason for the Season. The season, after all, is winter, which is caused by the fact that the earth rotates on a slightly tilted axis, which takes the Northern Hemisphere a little further from the sun this time of year. Jesus has nothing to do with it. Jesus also has nothing to do with a variety of holidays that take place in this season, such as Chanukah, Yule and Kwanzaa.

However, pagan symbolism such as fir trees, holly and mistletoe aside, Christmas is Christmas, and I have genuine sympathy for the people who are concerned that it is time to put the Christ back into Christmas. It seems a bit bizarre to me to celebrate the birth of a baby born in a stable by indulging in an orgy of consumerism. But how people conduct their celebrations is not the war.

No, the war on Christmas, on the man who declared “blessed are the poor,” is being declared by the folks who are determined to cut billions of dollars from programs that keep families from going hungry. The war on Christmas, on the man who overturned the tables of the moneychangers, is being conducted by financial institutions that expect the public to assume the responsibility for their losses on risky investments, while they reap the rewards. The war on Christmas, on the baby who could only find shelter in a stable, is being conducted by immigration policies that have no room for the notion of hospitality. The war on Christmas — on the man who said we will be judged on how we have fed the poor, given drink to the thirsty, clothed the naked, and visited those who are sick or in prison — is being conducted by those who would describe those in need as “takers” and those who think it’s a good idea to fill prisons with young men so that private corporations can make a profit.

Frankly, I couldn’t care less whether you wish me a merry Christmas, happy holidays or simply a nice day, so long as it’s done in a spirit of civility. Pipe Bach chorales and Handel’s Messiah out into the streets, and put up a Nativity scene on your lawn. Fine by me. Be my guest. But don’t put yourself in the role of Mr. Scrooge, loving the fruits of business so much that you care nothing for the poor, and then step out in the public sphere and declare your horror at the neglect and abuse of Christmas. For that is the real war on Christmas, and it looks like Christmas is losing again.

Who’s In and Who’s Out of Institutions (and the immigrants between)

September 12, 2013The British social anthropologist Mary Douglas had this to say about institutions:

Inside a religious body you get sects and hierarchies, inside an information network you get bazaars and cathedrals, it is the same, call them what you like. They survive by pointing the finger of blame at each other.

That about sums it up, doesn’t it?

Douglas is most famous for her theory of dirt: She claimed that human groups form solidarity by what we consider disgusting. For example, if your group considers eating sheep’s eyes disgusting, you’re unlikely to become very intimate with the group next door that considers sheep’s eyes a delicacy.

Douglas claims that human groups, or “institutions,” allow those inside the institution to point fingers at those outside the institution. As we stand inside and point fingers, we develop group cohesion: there’s an inside and an outside.

But, it doesn’t stop there.

Douglas thought that first we off-load responsibility for our actions onto an institution, then we begin to allow the institution to think for us. As a matter of fact, Douglas believed that our institutions operate exactly opposite from the way we generally think they do: we think institutions make small, rote decisions for us; but, actually, we allow institutions to do the big thinking for us, and we stick to the small stuff (–you know, such as consuming too many calories and avoiding exercise. Stuff like that.)

Because . . . it’s not easy bearing personal responsibility for the things that institutions such as government do. Yet, if we intend to lead an examined life, we must look in the mirror and ask ourselves what benefits we get from those things we off-load onto institutions.

Let’s think about government . . . oh, say, the United States government: bad immigration policy; institutionalized racism; millions of working poor; gun “freedom” that kills thousands per year, and poorly regulated industry, to name a few problems. Now, ask yourself, What benefits do I get by being in that group?

It’s disturbing.

It’s disturbing because Dr. Douglas is not saying, human beings form institutions and then wag their fingers at outsiders when they aren’t thinking about it or when we get lazy or when we fail to change wrongs. She isn’t saying those other people do that. She’s saying that’s what ALL institutions do. It’s disturbing because a basic fact of human nature is that we form groups, then we lose any ability to act morally concerning those things we have given away to an institution. Then we benefit from the immoral actions.

Now, you can say, “Oh, well, she’s just a crazy leftist feminist postmodernist, so, you know how THEY are!”

Or we can say, “hmm, that’s interesting! How can we use that human propensity both to better understand institutions that we don’t like, and those we do?

How can we use that idea to create institutions that encourage the sort of human action that we see as positive, rather than the sort that we see as negative?

I know you’re already way ahead of me on this . . . ideally, Unitarian Universalist congregations are places where people are not only encouraged, but required to question assumptions. Places where we encourage finger-pointing at systemic injustices, not at the people who may or may not be perpetrating the injustices, for whatever reasons . . .

If we look at Mary Douglas’s ideas from this perspective, they aren’t quite as crazy. Or quite as ivory tower!

Take, for example, immigration.

Consider for a moment that, as nations go, Mexico is not a a poor one. As nations go, the average Mexican is somewhere in the mid-range of income and social well-being for human beings on the planet. It isn’t that Mexico is poor, by international standards, but rather that the income disparity between Mexicans and North Americans is large–as a matter of fact, the disparity is the largest of any two bordering nations on earth.

That goes a long way toward explaining why people might consider crossing a border. To me, anyway, it’s hard to point my finger at a group of people trying to do that.

How have we–and let’s listen to Mary Douglas and include all of us–how have WE—the institution called the USA–responded to the immigration issue? Rather than facilitating the flow of people back and forth across the border, we have tried to stop the flow–we are still following that policy.

Now, I’m old enough to remember when the border was porous. People came here for summer work, then went back to Mexico–they went back home–for the winter. People can’t do that anymore. Because we have spent billions of dollars to stop them. They’re stuck here.

What would you do, if you found yourself stuck in a foreign country, no way out?

First you would go to the embassy, right?

Then you would start calling on your support network . . . family and friends.

Then you would get out your credit cards . . . see if throwing money around might help . . .

What if your loved ones were across the border?

How long would it take before you just took off walking . . . ?

I have a challenge for you: listen to Mary Douglas and get outside your comfort zone. Call yourself on one of your prejudices . . . . Call your own bluff on one of the “institutions” where you sit comfortably and point fingers from . . .

Maybe it’s the institution called race. Maybe it’s the institution called social class. Perhaps it’s the institution called education. Perhaps you wag your finger at close-minded people.

Whatever.

Try reminding yourself this week that, as psychologist Steven Pinker puts it,

“Our minds are organs (like the lungs), not pipelines to the truth.”

Our minds are organs, not pipelines to the truth.

Try it. Actually realize that your brain is an evolved organ and has its limitations. And your brain is NOT an institution.

This week, call yourself on one of your prejudices. Call yourself on one of the things you get away with because of an institution you belong to. Step outside your comfort zone. Actually listen to someone who your prejudice tells you can’t have ANYTHING valuable to say.

Instead of pointing a finger and even wagging it a little, sit back and listen.

Try it.

A Prayer for those Whose Hearts are on Fire

July 13, 2013A prayer after the not guilty verdict of George Zimmerman

Spirit of love and justice,

Tonight I am angry.

May my anger burn cleanly,

Joining the light of so many hearts on fire.

May we know anger as a source of strength,

Anger that seeks to purify,

Anger that has as its fuel the power of truth,

Anger grounded in love,

May I live my life so that Trayvon Martin did not die in vain.

May my anger give me strength to take action,

To stand my own ground, the ground of compassion,

The ground of justice which dwells beyond courts of law and its technicalities,

The ground of worth and dignity of every human being.

May we live our lives so that Trayvon Martin did not die in vain,

So that African American youth are not seen as threatening merely because they exist.

May we take steps to bring such a world into vision.

Concrete steps, particular steps, in our own communities.

Anger used well is energy for life.

Anger turned inward saps the strength,

Anger turned to rage severs real connection.

May I use this holy anger well,

Use my privilege well, use my voice and my strength and my power.

May we draw on the strength of those who have turned anger to love through the generations,

those who have made a way out of no way,

those who have burned but not been consumed by this holy fire.

May we remember the strength of our connections to the generations,

The ancestors and those yet to be born,

The strength of our connection to the fighters and the lovers,

May I live my life so that Trayvon Martin did not die in vain.

May we live our lives so that Trayvon Martin did not die in vain.

May he live forever in our deeds, in our commitment to a justice

Which can never be found in any court of law.

Courage

June 5, 2013 I expect by now you’ve heard the story: seen the pictures of the people bludgeoned by water cannons, the dog in a gas mask, the sufi dervish whirling in the street with deliberate disregard for the danger of his surroundings. It started simply enough. A group of people decided to sit in to protest a public park being razed in order to put in one more shopping mall. A group of people, young and old, decided that they had had enough of their country being sold off to the highest bidder, enough of the rights of the people being stripped away at the pleasure of the powers that be. And so they went to sit in the park. And there they sat as the bulldozers came at them, non-violent protesters in the long and distinguished lineage of Gandhi and King and Tiananmen Square and so many others. And in the long and shameful lineage of the British in India and Bull Connor and the Chinese government in 1989 and so many others, the Turkish government responded with water cannons and pepper spray, with police in riot gear prepared to do whatever it takes to subdue the population.

I expect by now you’ve heard the story: seen the pictures of the people bludgeoned by water cannons, the dog in a gas mask, the sufi dervish whirling in the street with deliberate disregard for the danger of his surroundings. It started simply enough. A group of people decided to sit in to protest a public park being razed in order to put in one more shopping mall. A group of people, young and old, decided that they had had enough of their country being sold off to the highest bidder, enough of the rights of the people being stripped away at the pleasure of the powers that be. And so they went to sit in the park. And there they sat as the bulldozers came at them, non-violent protesters in the long and distinguished lineage of Gandhi and King and Tiananmen Square and so many others. And in the long and shameful lineage of the British in India and Bull Connor and the Chinese government in 1989 and so many others, the Turkish government responded with water cannons and pepper spray, with police in riot gear prepared to do whatever it takes to subdue the population.

Who will not be subdued. Who continue to flock to the streets. I understand the courage of those first protesters, the ones who decided to sit down in a park and make their presence felt, who were willing to see what would happen when they demanded that someone take the needs of the people, and not just the corporations, into account. Sometimes you summon up what is inside of you and do the brave thing, walk the talk. But what about all those other people, the ones who joined the protest once they knew about the water cannons and the pepper spray, once the news spread (by word of mouth and social media, since the official media kept a complete blackout) of the injured and the dead? What about them? What does it take to knowingly walk into that kind of danger and chaos?

It takes, I think, an allegiance to a self that is greater than the self that feels the police batons and the pepper spray—a self that is injured not by physical indignities, but rather by moral ones. Call it Soul, if you will, this larger self, or call it Community Consciousness or Human Dignity or Living in the Kingdom of God. Whatever it is, it does not belong to a particular time, or place, or religion. It’s what led Gandhi, the Hindu, and King, the Christian, and the young man (Buddhist?) who faced down a bulldozer in Tiananmen Square to counter violence with persistent love. It’s what holds the Sufi dervish dancing in the streets of Istanbul and Bill McKibben getting arrested on the steps of the White House in protest against the Keystone XL pipeline. Who we are is bigger than who we are.

Not all of us. Not all the time. But enough of us, enough of the time, that it seems possible that love might have a chance against greed, that freedom and justice might sometimes prevail. Not all the time. But maybe enough.

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210