Who Would Jesus Fence Off?

May 30, 2012Last week a Baptist pastor by the name of Worley got a fair bit of internet attention for declaring that gay people should all be stuck behind an electric fence – lesbians in one area and “queers and homosexuals” in another, where food could be dropped to them from an airplane until they all eventually died off because they couldn’t reproduce. OK, just for a minute we’re going to set aside things like the obvious fact that straight people would just go on having gay babies like always, thereby replenishing the supply of queers outside the fence. Let’s even let go, for the moment, of the congregants who cheered during the service and supported their pastor with a standing ovation a week later. Not much you can do about stupid and mean except call it what it is.

No, what I’m thinking about at the moment is the fence. The idea that we can identify the undesirables and wall them off. For Worley, the world would be a more virtuous, lovely place if you could just stick the “queers and homosexuals” off someplace where he wouldn’t have to look at them. Which doesn’t strike me as all that different from wanting a giant wall along the US/Mexico border. Which, perhaps, is not entirely unlike wanting to live in a gated community, the kind where a neighborhood watch patrolman might shoot a kid who looked as if he didn’t belong there and might be up to no good.

There’s something deeply tempting about the idea that we can make ourselves safe by simply building a wall between ourselves and the thing that scares or disgusts us. It is, I suppose, human nature to believe that we can find security by fencing out the “other.” Which is why the role of religion is supposed to be to remind us of our better selves, to push us toward letting go of the scared hind brain that wants to wall ourselves off from danger, so that we can move instead toward a more evolved self that longs for peace built on a foundation of love.

You can search the Christian Scriptures all day for a suggestion from Jesus that we should wall ourselves off from those who are “different” or “disgusting” and all you’ll find are stories like that of the Good Samaritan, where the hero is a member of a despised ethnic group, or of Jesus eating with a tax collector – someone utterly unwelcome in polite society of the place and time. Pastor Worley may be speaking for the large percentage of Americans who have entrenched themselves in fear and loathing, but he sure as heck isn’t speaking for Jesus.

On Being a Beginner Again

May 29, 2012If someone were to ask you whether you’d rather be an expert or a beginner at something (pick any activity that interests you), I’m guessing that you’d probably say “expert.” I know I would. Who wouldn’t want complete mastery of a subject? As someone who just started playing the guitar five years ago, I think it would be a lot more fun to play like Eric Clapton than it is to sit and plunk out the few chords I know. When we gain mastery over a subject, whether it’s playing the guitar or nuclear physics, it frees us up to experiment, to be creative. We’re no longer limited or bound by our abilities. Expertise gives us room to have fun, because we don’t have to work quite so hard. And in our outcome-based society, experts are held in high esteem. They serve as role models for others. They make a difference in other peoples’ lives.

I learned to ski when I was a child, and by the time I was in my twenties I was pretty good at it. I’d call myself an “expert” skier. While there were some steep mountain trails out West that gave me pause, I could negotiate pretty much any terrain, and generally do it with some degree of grace and finesse. Then, a funny thing happened: I got bored. I lost the zest and zeal I had for skiing. Riding up the mountain and skiing down it didn’t give me the same rush, the same satisfaction that it had when I was younger. Now my skis sit idle all winter, and I don’t miss it much. So, perhaps expertise isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

Now, I’m trying something new: paragliding. And I find myself a beginner once again. Trying to figure out the right way to hook into the harness. Learning the right technique for inflating the wing so that it comes up off the ground and flies directly overhead. Studying the winds and the clouds, and looking at weather in a whole new way. Every aspect of this sport is new and exciting to me. To say nothing of the beautiful views you get, sailing above the countryside.

Am I anxious to join the more experienced pilots, catching thermals and soaring with the hawks and eagles thousands of feet over the mountains? Of course I am. But I’m experimenting with not being too anxious to get good. With staying in this place where the learning curve is steep, and not moving through it too quickly. Of not getting frustrated when I get tangled up in the lines when a gust of wind blows me sideways before I even get airborne, or when my flights last all of three minutes while my friends are surfing the clouds for hours.

Zen Buddhism encourages the use of Shoshin, or “Beginner’s Mind.” With Beginner’s Mind there are limitless possibilities. Creativity, enthusiasm and optimism abound when we have Beginner’s Mind. The very newness of the activity fires our creative juices and we approach it with a sense of wonder and awe. One writer has said, “With Beginner’s Mind, there is boundlessness, limitlessness, an infinite wealth.”

We don’t need to be an actual beginner to have Beginner’s Mind. We can approach even time-tested activities, those in which we’re experts, with Beginner’s Mind. We can enter into any activity with complete openness and curiosity, with a deep desire to learn, with a will to “fall down seven times and get up eight times” as the Buddhists say. It’s easier to have Beginner’s Mind when we’re actual beginners, but we can approach even the most familiar activities with Beginner’s Mind and make them new again.

Whatever way the winds carry you in the weeks ahead, I invite you to take along your Beginner’s Mind, and see where you end up.

Give It All Away! Wisdom of the plants

May 27, 2012These days, as spring turns to summer, the garden is insistent with one message: Give it away, or lose it all.

Early in the development of a garden, it’s about procurement. Picking out plants, choosing a place for them, seeing how they do. With the kinds of perennials I tend to favor, that is both fun and highly interactive. Many of the flowers in my yard have stories that go along with them about who gave them to me, stories that make them that much more beautiful.

And now, as I go into the fifth or sixth summer of having turned my yard into flowers, herbs and vegetables, it is imperative that I give stuff away. If I don’t, if I try to hold onto all of the abundance for myself, the whole thing will die.

And so I join my local facebook group for perennial exchange and post regularly what I have to offer, “Bee balm. Rudbeckia. Strawberries. Grape thistle. Dig your own!” People come with shovels, apologetic about taking too much, and I want to tell them, there is no such thing as taking too much!

I go to farmers’ markets, see people paying $5 for rhubarb, $25 for a hanging basket full of morning glories, and though I want farmers to make a good living, still I want to whisper, “I’ll pay you to come to my house and take that same thing!” I refuse to allow a friend I am there with to buy morning glory plants, my voice so sternly admonishing, you would think she wanted to eat kittens. I convince a friend into native foods to try to eat Jerusalem artichokes; I happen to have hundreds. I offer plants to neighbors who walk by and stop to admire, to friends planting gardens at their kids’ schools. I plant lupines and ferns and hostas in pots from garage sales and sell them myself at a garage sale, to start others on their gardening journeys.

There is so much wisdom, so much life, in what the garden is teaching me about giving it away.

First, in order to give away what I can’t use myself, I need to be in constant relationship with many people. Weeding and throwing on the compost pile is the simplest way to say goodbye to too many lupines and kiss-me-over-the-garden-gate plants; it is tremendously more fun to give them to people who will love them! When someone I can’t remember ever talking to stops by and says, “We have been eating raspberries all week from the shoots you gave us,” it makes my day. It’s unlikely that a few people will want all I have to offer. I must diversify channels for the abundance to flow!

Second, it’s OK to change my garden, to simplify. The “tall garden” I loved turned out to block my neighbor’s view of the lake, so now I have a short garden I love, with the tall plants elsewhere in my yard, and the yards of others. The vine that promised beautiful flowers turned out to be so vigorous it scared me–dig that out and pass it on to someone who wants to cover an old barn!

And finally, the most beautiful flower becomes a weed if it’s growing someplace you don’t want it. Along with aphids, beetles, early frosts, flooding rains, and sudden frosts, I get to arbitrate life and death in the garden! I am the creator of this plant haven so I also am given the power to be the destroyer—to decide that vinca is, after all, not what I want, even though it is thriving in my yard, or that the fancy lilies simply get on my nerves with their showy blossoms; I prefer more humble snapdragons. For those of us who tend towards codependency and putting others before us, gardening is a great exercise in getting to put our own needs first!

There are hundreds more messages I receive from the plants on a regular basis; I will be sharing these as they arise. One of them is “To everything there is a season,” and today’s season is about sharing and relinquishing the abundance of life in order to treasure what is particularly yours to treasure.

Sex and War: Thoughts on Memorial Day Weekend

May 26, 2012For Sunday, May 27th, I titled the worship service at the Church of the Restoration, “Sex and War: Love and Hope.” My title mostly came from a 2008 book by Malcolm Potts and Tom Hayden, Sex and War: How Biology Explains Warfare and Terrorism and Offers a Path to a Safer World. It’s a very interesting book, but not what I am thinking about this afternoon. When I arrived at the church today, the lovely man who changes the lettering on our sign had put these words, “Sex and War or Love and Hope.”

The sign startled me. It just wasn’t at all how I thought about the relationships between these four things. Now, like many ministers, I am the kind of person who when surprised by something just starts thinking about it. Some of my family members say (kindly, usually) I think too much about strange things! One of my colleagues recently bemoaned the fact that anything can become a story for a sermon or a blog. We observe ourselves and we observe our own thinking. My friend would like to just be in the experience, and there is certainly something to appreciate about being in the moment, in the flow. In fact, much of spiritual practice is designed to help us to be “in this very moment.” Still, there is also much to appreciate about observing ourselves, especially observing ourselves without judgment but with curiosity.

When something startles us, when two unusual things come together in our minds, we can be opened to creativity, new ways of seeing things or new questions. So, when I saw the sign, I thought, “What was he thinking when he put the word “or” on the sign?” Very briefly, I wondered if I should ask him to change it but thought, “No, it’s kind of provocative that way. What will passersby think that it means?”

I thought that the wording seemed to put a negative implication toward sex. Now, this might be true of some ministers and some churches, but is not at all true for this minister. I think sex is a vital, essential part of life and indeed can not only be deeply loving but also deeply spiritual. Well that thought lead me to think about the relationship between war and love and hope. It seems to me that it is complicated.

I have known loving warriors. I live in Carlisle, Pennsylvania which is the home of the Army War College; colonels come to Carlisle for a year of study. The Carlisle Barracks also houses the Peace Operations Training Institute whose mission is to study peace and humanitarian relief any time, any place. Their mission is in part, “We are committed to bringing essential, practical knowledge to military personnel, police and civilians working toward peace worldwide.”

(www. http://www.peaceopstraining.org/e-learning/cotipso/partner_course/725)

I learned by listening to the colonels. Those colonels who study peace and war are not usually leaders who want to go to war. All of those who go to war often go with love in their hearts: love of family, friends and country. Combat veterans tell us that their actions are motivated by love for their comrades, the “band of brothers, and now sisters,” who are right there beside them. We who stay behind love those who go. We all hope and pray for their safety. We all hope and pray for peace.

Now, my prayer is that there be no more war; my hope that we will all learn to live in peace. My basic stance is that of non-violence and pacifism. I never want people to go to war because they have been intentionally deceived or for corporate profits. But may we never forget the worth and dignity of all, the love and courage of those who go to war and of those who stay behind.

All these thoughts came from seeing the word “or” on our sign, and as it happens, he used that word because we don’t have a colon.

May love, hope and wisdom guide and sustain you.

Rev. Kathy Ellis

Safe Harbor

May 25, 2012Press power on the remote control, television on

and every moment of viewing we are confronted with images that shame us into wanting to reject parts of our being

turn our bodies and ourselves into slimmer, younger, lighter, leaner

smarter, whiter, wealthier, straighter versions of our selves.

Magazines tell us what not to wear

along with 7 surprising things that turn guys off

And what men want during the NFL halftime.

Messages crafted to ensure we remember that

who we are – at our core – is not good enough.

//

Would you harbor me?

Would I harbor you?

Asks the Sweet Honey in the Rock song and:

Would you harbor you?

Would I harbor me?

How much time do we spend attempting to do the impossible?

How much energy…how many of our resources do we expend running away

From our bodies

From our identities

Our histories

Our stories…from our very own selves?

How much time, energy, and resources do we spend

not loving our bodies

fearing ourselves because who we are, is not

who we see reflected back at us in “normative” socio-cultural stories and images?

Because we’re actively being conditioned to cling to a mythical norm?

A while back on National Coming Out Day

I decided to feed my facebook obsession

by checking out the page

Wiping Out Homophobia on Facebook

There, in the photo album, I found photo after photo of

same-sex couples laughing, smiling, holding each other

women, men – people – marrying, playing, loving and…

I also found this note from Paul…growing up in a world

in which his identity is continuously questioned and made wrong.

A world in which some who proclaim to speak on behalf of God

advocate death or caging LGBT individuals until we die off

Paul writes:

“I have to tell you that for the past few weeks, I have been pretty low and had pretty dark thoughts about my life and what to do. I had been bullied at school and things got so bad that I thought about doing something really bad.

Well, I talked to you and you told me to join local groups and online groups to get support from people in my age group who know what I was going through.

Well, I joined an LGBT group in the next town and about 8 online. I now have some great new friends in real life and some online who I’ll never met but who I talk to a lot.

I know this is what everyone says, but I don’t feel so alone now, I am not like the only one. …I just thought I’d keep you up to date as you were all so kind to me. Thanks to K. and L. for talking me round and to everyone who said positive things, they really did help.”

This broke my heart…and in some small way, it offered some hope.

In a culture that is slow to extend

safe harbor for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender

children, youth, adults – elders…

In a culture that supports heterosexism & homophobia

In a culture that promotes messages of same-sex deviance often enough,

many – especially youth – begin to

internalize that message.

Believe that message.

Begin to question their, my, your, our inherent worth and dignity

It is easy to feel other-ed. To understand others and sometimes oneself as strange, deviant…

It would be effortless to create a list of all the ways we – who are

queer – have contributed to society…have enhanced the world.

It would be easy to catalogue the gifts of all the LGBT “strangers” among us.

And. Here’s the power of affirming the inherent worth and dignity:

It’s inherent. It matters what we do, sure. And, it matters more that

we simply are.

We…any one of us…shouldn’t need to be any more special to be accepted. To be loved.

To be equal.

We only need to be here. To show up. To love…

That’s the nugget of wisdom in the first principle: inherent worth simply “is.”

To love ourselves is the equivalent of a tiny revolution

To love all those unchangeable innate beautiful truths that

make us who we are

and the imperfect pieces and parts that we argue with

That we shove away

That we suppress

That we pretend we feel okay about…

when we embrace all of those parts

and come to see them as holy

it is the equivalent of a tiny revolution.

In her book: All About Love: New Visions,

bell hooks writes:

“When we are taught that safety lies always with sameness,

then difference, of any kind, will appear as a threat.

When we choose to love, we choose to move against fear –

against alienation and separation.

The choice to love is a choice to connect – to find ourselves in the other.”

When we’re taught that safety lies in sameness

when we’re taught that the only safe community is

a community of people who look like, dress like, think like we do

When we’re taught that only certain body types belong in the public sphere

When we’re taught that only people of certain heights or gender identity

or educational background or sexual orientation are capable of leadership

then we begin to fear everything in ourselves

and subsequently in others – that fail to fit what we’ve been

carefully taught.

We begin to fear everything that differs from the constructed “norm.”

And. What we fear, we seek to destroy.

But, when we – as individuals, as social systems with power,

as a community –

choose to love…move against fear…and connect

with difference, with that which appears to be strange – then

we make room for the Holy to thrive in and amongst us.

The tiny revolution in Paul’s story was just that.

A community that willingly created room for him – holy and inherently worthy –

to show up

Willing to extended safe harbor.

I want it to be true that we can create such harbors for

ourselves and for others.

The Meaning of Memorial Day

May 24, 2012I thought I understood the meaning of Memorial Day. I thought the military uniform hanging in my closet taught me the meaning of Memorial Day. I thought that growing up the child of a soldier, and the grandchild of a sailor taught me the meaning of Memorial Day. But I was wrong.

Day. I thought that growing up the child of a soldier, and the grandchild of a sailor taught me the meaning of Memorial Day. But I was wrong.

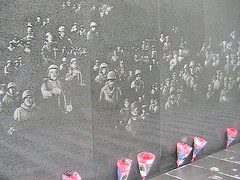

I sensed the meaning of Memorial Day. A few years ago I preached a sermon about standing at the Vietnam Wall with my father, watching him trace names of friends across the wall. It was the only time I ever saw tears in his eyes. I saw my grandfather visit the Punchbowl WWII memorial in Hawaii, and I saw those same silent tears.

I thought I knew the meaning of Memorial Day… but I did not. Not until my wife came and told me that the television news had just reported the death of my friend, military partner, and former roommate in the Al Anbar province of Iraq on December 6th, 2006. It was not until I realized that I too would one day have a name to trace across a memorial somewhere, the name of Travis Patriquin, that I learned the meaning of Memorial Day.

While I do not believe in a spiritual place called hell, I think General William Tecumseh Sherman was right when he said that “War is Hell”. It is a hell that exists in this time, in this world, not in some metaphysical afterlife. I wish with all my heart we could rid ourselves of it… I wish for the day to come when we no longer send our young men and women off to walk through that hell. I wish for the day when our problems are solved by meeting, not by killing. It is rarely those who should be meeting that instead face the killing. I wish with all my heart for what military forces we have to become a tool of peace, not a weapon of war.

Clinton Lee Scott once said “Always it is easier to pay homage to our prophets than to heed the direction of their vision”. The true meaning of Memorial Day is not homage… it is not to honor those who have served, those who have died for our nation. Oh, that is what the media will tell us, what the President will say when he lays a wreath at Arlington National Cemetery in a few days. I expect him to strike a tone of “honor our dead, and standing resolute.” No, it is not honor that our war dead ask of us. Honor is the easy way out of the vision they call us to.

The true meaning of Memorial Day is to remember. It is to remember that the cost of war is almost always too high. The true meaning of Memorial Day is not to honor our dead, but to remember the price they paid. To remember the price their families pay. To remember the physical and psychic wounds that the survivors of war, on all sides, carry with them till the end of their days. To remember the lives never lived. To remember the horrors unleashed upon civilian populations by the tools of modern warfare. To remember…

I want to cease thinking of Memorial Day as if it were a holiday, for it is not. I want to end the Memorial Day sales and the picnics, the trips to the lake and the hamburgers and hotdogs with stars and stripes napkins. We should never “celebrate” Memorial Day. I want Memorial Day not to be a holiday, but rather a National Day of Mourning.

It began as “Decoration Day”, a day when families and friends would go to cemeteries and place flowers and flags upon the graves of those who had died in the Civil War. From those graves they heard, and they remembered the cost of war. I want to return to that spirit, so that the memory of the true costs of war is fresh in our minds, renewed annually… so that perhaps we can honor our dead by sending no more to join them.

Keep your Memorial Day plans, if you have them, but remember the “reason for the season”. We do not honor the casualties of war with flowers and speeches, but by truly and deeply remembering the cost of war when we contemplate sending our service members of today into harm’s way. We honor them by remembering that war is a hell that should rarely, if ever, be unleashed.

Remember.

Yours in faith,

Rev. David Pyle

www.celestiallands.org

Chaplain, U.S. Army Reserve

What Kind of a Parent is God?

May 23, 2012

Women’s studies classes in college introduced me to the idea of feminine images of God/goddess. Frankly, I hadn’t really much thought about it up to that point. God was simply not an idea that I much related to, since God seemed to be distant, vague, and to alternate unpredictably between benevolent and judgmental. But a mother God, a God with a (metaphorical) lap to sit in, a God who was one with the earth and fertility and creativity, that kind of God started to sound like something I could relate to.![]()

It wasn’t until much later, when I became a parent myself, that I realized that the whole Mother God/Father God split was patently unfair to men. The Father God I heard about from conservative Christians was a punitive, “wait ‘til your father gets home” kind of God, whose kindness was at a distance and whose judgment was close. It’s one version of being a father, and perhaps the version that is still popular amongst those who hold to this theology. But I know a whole lot of dads who are loving, nurturing, reliable and supportive. It turns out that the image of a Father God is less the problem for me than the kind of dictatorial father that that God is supposed to be. For what it’s worth, given that Jesus addressed God as “Abba,” the Aramaic equivalent of “Daddy,” it’s a pretty good bet that Jesus didn’t have a distant 1950’s God in mind either.

The Women’s Movement didn’t just give us the notion of a feminine image of the divine. It also gave us a revised understanding of what it means to be a parent. After years of recoiling from the notion of a Father God, maybe I’m ready to embrace the idea of a Father/Mother God who is the kind of parent that I aspire to be: a parent with ample love and reasonable limits, who tries to instill my values but knows that ultimately, my child will need to choose for herself, according to her own experience and view of the world. That kind of a God would value exploration and creativity above blindly following a narrow set of rules, and would ask “did you have fun?” rather than “did you win?” about my activities and endeavors. That kind of God would treasure my individual quirks, but encourage me to work through my failings to become more responsible, more compassionate, more aware of others and what I could do to improve life for those around me and the world as a whole.

That’s not the kind of God I see preached by people who disapprove of contraception and Gay people and a woman’s right to control her own body. But I look around at so many women and men I know who are terrific parents, and I think that maybe God is alive in the world after all.

Rev. Dr. Lynn Ungar is minister for lifespan learning of the Church of the Larger Fellowship. (www.QuestForMeaning.org)

Paying Tribute

May 22, 2012In her best-selling Hunger Games trilogy, Suzanne Collins imagines a world of the future—a dystopian reality in which North American society has been replaced with a world where workers toil for the good of a small elite, threatened with the use of force, and given hope only by the small chance of winning a deadly game.

What makes the world of The Hunger Games so eerie is that we can see remnants of our present-day reality in it—enough remnants that it scares us to think that maybe, just maybe, we are headed down a path towards totalitarianism.

And while The Hunger Games is a work of fiction and of fantasy, we would do well to understand the signs in our current society that make Suzanne Collins’ disturbing imagination all-too-real.

In The Hunger Games, teenagers, called “tributes,” from each of the oppressed districts are forced to fight to the death in a reality television show broadcast throughout the nation. Their gruesome deaths are entertainment for the elite people in the Capitol, and the entire nation is forced to tune in and watch their children die.

That certainly isn’t reality, is it?

The reality is that our nation exists in what Chris Hedges, author of Death of the Liberal Class, calls a state of “permanent war.” Hedges writes, “since the end of World War 1, the United States has devoted staggering resources and money to battling real and imagined enemies. It turned the engines of the state over to a massive war and security apparatus.” We are kept in a constant state of fear that mutes dissent in the name of patriotism and fuels a war machine that benefits a privileged elite.

Our wars require not only a steady stream of money—taken from our paychecks and pockets and diverted from health care, our social safety net, education, and infrastructure—but also a steady stream of young, able-bodied people willing to die for our country. All too often, they do.

I am not suggesting that the death of US troops is entertainment for the elite, as is the death of young people is in The Hunger Games. But their death serves to reinforce a status quo that there are people whose interests are served by our nation being at war. The death of brave young soldiers helps us silence objections to unjust wars being fought in our name, it helps us dismiss Occupy movement as “fringe elements,” and it helps us rationalize police brutality towards non-violent protesters.

Lest we appear unpatriotic, those of us morally offended offended by the deaths of US soldiers stay eerily silent about what is fueling those wars.

We cannot afford to remain silent about the fact that corporations are profiting from this state of permanent war, and those same corporations have wrested control of our political and economic systems.

As we approach our annual celebration of Memorial Day, we will pause to mourn the lives lost in service to our nation. It is right and good to do this. Once we are done with our moment of silence, however, we owe it to our soldiers to raise our voices.

We must insist on a society where people matter more than corporations. Where the lives of young people are not used as disposable input into a system of profit-making and wealth creation.

We must insist on a society where political power is checked and shared—and not allowed to run amok through Super PACs and corporate donations. Where the wealthy and the poor have equal access and equal voice, where money is not speech, and where corporations are not people.

We must insist on an economy based in love and compassion, rather than fear and greed. We must insist on an economy based in mutuality rather than coercion. We must insist on a nation that treats the “least of these” in the human family as if they were the divine in our midst.

We must raise our moral voices loudly, my friends. We might not find ourselves in the Hunger Games if we do not, but to create the future we want to see we cannot remain silent.

The Exquisite Joy of Being Miserable

May 21, 2012So I’m listening to Garbage’s Only Happy When It Rains, mindlessly singing along with Shirley Manson. Pour your misery down, pour your misery down on me.

I’m sure the song is mocking those Eeyores among us, the Debbie Downers, the ones who feel so good when they “feel so sad.” I mean, haven’t we known those types? The ones who excitedly call us up to tell us about the pitfalls of their newest romance, or are the first to post some sort of horrible national news on Facebook, the people at a party who leave us looking around frantically for an escape. My only comfort is the night gone black .

Of course, the song couldn’t be talking about me, right?

I mean, yeah, I’m a Gen Xer, so my whole generation takes pride in being cynical, dark. No Pollyanna idealistic Boomers here, no sirree. The first we knew of politics was hearing the grownups talking about Watergate. We grew up hearing dire predictions about the environment, about how we would be the first generation less successful than our parents, we were latchkey kids of divorce. I‘m only happy when it’s complicated …

But me? No, I’m hopeful. Optimistic.

Except for when I’m not.

I’m riding high upon a deep depression …

That’s the thing of it, isn’t it? That no one talks about. There is pleasure in being miserable. Feeling sorry for ourselves. I don’t mean a serious depression, from which you can’t seem to extricate yourself. No, I’m talking about those run-of-the-mill blues, ennui, moodiness. Remember the child’s rhyme? Nobody likes me, everybody hates me, I’m gonna eat worms … Sometimes, we just have to wallow in our unhappiness, relishing the exquisite joy of being miserable.

When we can do that, when we can be honest, we are claiming our choice in the whole matter. Buddhists say that pain is inevitable, but suffering is optional. Our society talks disparagingly about pity parties, but I think we all need one every once in a while. Like with all good parties, we need good food, good drink, good entertainment. Bring on the comfort food, the milkshakes, the sappy movies to cry over, whether it’s Steel Magnolias or Field of Dreams.

Ecclesiastes says to everything there is a season, and after the pity party, it’s time to clean up. Wash the dishes, dry the tears, change the soundtrack.

Misery can feel good, but happiness feels better.

Holy Curiosity

May 18, 2012In the story of the Little Prince,

there is a compelling scene in which he

arrives on a new planet and encounters a businessman.

We know it’s a businessman because he is counting

he is too busy counting to lift his head in response

to the Little Prince’s greeting.

He is behind his desk working on a huge ledger,

counting, much like this:

“Three and two make five. Five and seven make twelve. Twelve and three make fifteen. Fifteen and seven make twenty-two. Twenty-two and six make twenty-eight. Twenty-six and five make thirty-one. Phew! Then that makes five-hundred-and-one-million, six-hundred-twenty-two thousand, seven-hundred-thirty-one.”

When he takes a breath, the Little Prince asks:

“Five hundred million what?”

It is such a simple question isn’t it?

But, the man, the one counting only responds

to the Little Prince in this way:

“Eh? Are you still there? Five-hundred-and-one million

I can’t stop…I have so much to do! I am concerned with matters of consequence.

I don’t amuse myself with balderdash. Two and five make seven…”

Matters of consequence.

There is he was, behind his desk counting without pause

counting a thing of beauty whose name he could not remember

“The little glittering objects in the sky” he called them.

Stars!

He was counting and recounting stars, gathering them up

by the millions, owning them, banking them in hopes of one day

being rich from selling them.

He was tending to matters of consequence.

The businessman in this story is by no means unique!

When invited into a moment of human connection

When invited to ponder the little glittering…the stars,

to notice and grow playfully curious about them

He declined. He would lose track of counting.

He would have to stop, break away from his ledger, look up

…take in and behold the “little glittering objects in the sky.”

The stuff of dreams…

To take them in would mean opening himself up to

learning more…

He declined because the matters of consequence to which

he was attending were far too important and could not wait.

All questions were interruptions…

All moments of being invited to engage were “balderdash”

he had no use for the person before him seeking

to be in relationship

So it is with all of us sometimes.

We are drawn into important tasks and forget

the whole world around us ready for our curious gaze.

What if we attended to each other….

To those ordinary encounters and conversations with

intrigue?

What if instead of clinging to certainty

we paused and made room for holy curiosity?

The poet Rumi writes:

This being human is a guest house

Every morning a new arrival.

A joy, a depression, a meanness

Some momentary awareness comes

As an unexpected visitor.

Welcome and entertain them all, he says.

Be grateful for whoever comes,

Because each has been sent

As a guide from beyond.

Every moment, every interruption, has something to offer

something to teach…

The beauty is in being able to greet each new or familiar arrival

with a learning mind rather than a knowing mind.

And, forgive ourselves when we are not able to…

What if you had one moment today in which you were

gently interrupted from “tending to matters of

consequence” or in which you encountered the unfamiliar

What if you paused and viewed that moment as a guest?

An unexpected visitor from whom you had much to learn.

What questions would you ask?

How would you listen?

How would you choose to be?

~ Rev Alicia R. Forde

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210