Confronting the Legacy of Slavery in the North

September 25, 2017Public Testimony, Van Wickle Slave Ring, September 25, 2017

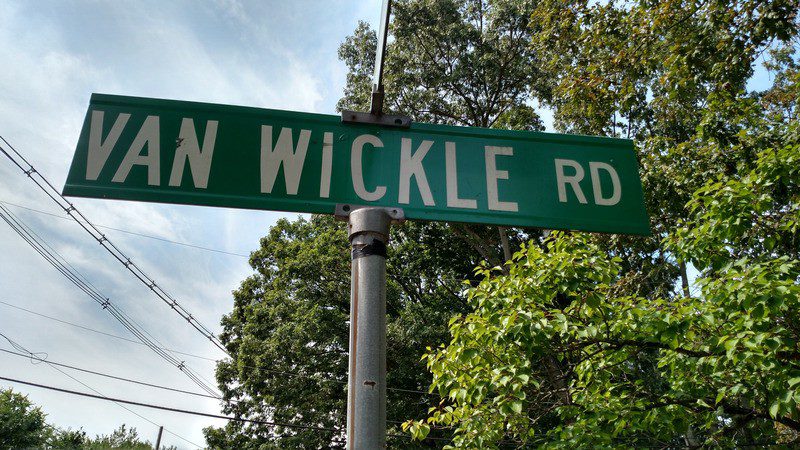

To the East Brunswick Township Council, New Jersey It is my honor to serve as the settled minister of the Unitarian Society, located at 176 Tices Lane, which has made East Brunswick our home since 1964. Let me express my gratitude for your attention this evening and the service you offer our civic society. In speaking before you today, I want to be clear that I speak on my own behalf. Over the summer, as I familiarized myself with local and state history, I learned of the Van Wickle Slave Ring. I believe the Council is familiar with this part of East Brunswick’s history wherein Jacob Van Wickle, a Middlesex County judge, and resident here, used his court in 1818 to send nearly one hundred African Americans into permanent slavery. At the time, once these activities were uncovered, there was public outrage and this incident of human trafficking was brought to an end. Though others were indicted, Van Wickle was not; yet the historical record makes it clear that he was at the center of this abuse of power. Not all the names of those nearly one hundred people have been saved for posterity, but some were. The names I speak aloud now are some of those people who lost their freedom: Harriet Susan Mary Augustus Rosinah, just 6 weeks old Hercules Dianah Dorcas Not fictional characters, but people with real lives: misled, stolen, sold back into slavery. Next year marks 200 years since this travesty took place. It seems a necessary and fitting time to tend to this aspect of the town’s history. The town has a street named after this infamous person. It is my understanding that at the time of the naming of that street, Van Wickle’s part in the Slave Ring had been erased — whitewashed. Those who chose his name for the street could not have known of his evil deeds.They did not know, but we know now. And we cannot unknow.I thank the Council for their recent directive of the Township Administrator to explore changing the name of Van Wickle Road, so that it is no longer the inadvertent glorification of a profiteering slave trader that it has become. I offer my support in whatever ways might be of use to help make this a reality in the near future. I know that there are others in my congregation who would do the same. This past August the nation saw Charlottesville erupt with white supremacists bearing torches and hatred. Those events moved the country to revisit the longstanding national dialogue about Confederate monuments and the ways they glorify those who fought to maintain slavery. It is too easy to think of this as a Southern issue, or an issue of some other locale. But that is not true. East Brunswick has its own commemoration of a notorious act of white supremacy. It is time we change this. Thank you for your time. Reverend Karen G. Johnston

Confronting the Legacy of Slavery in the North was originally published in Quest For Meaning on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Moving Toward Freedom

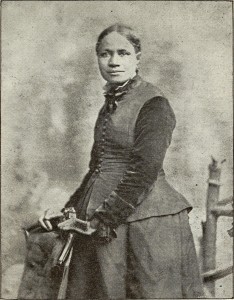

March 31, 2016Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was born a free Black woman in Baltimore, Maryland in 1825. She was raised in the household of her uncle, an educator and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) minister. He was also an abolitionist—a person who objected to the enslavement of blacks. Harper became an educator and abolitionist as well. She also became a writer, publishing her first book of poetry at twenty and later in life publishing the first short story by an African American woman. Her writing often urged Blacks, women, and people in oppressed groups to take a firm stand for equality and freedom.

In 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was passed. It became dangerous to be a free Black in Maryland because slave owners could claim Black people were runaway slaves and force them into slavery. So, Harper moved farther north to Ohio and then to Philadelphia. She taught, ran part of the Underground Railroad helping slaves escape to freedom, and lectured around the country.

In 1863, abolitionists celebrated success with the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the slaves. But there was a long road ahead to full equality, and Harper spent the rest of her life working for women as well as African Americans to have access to full freedom and justice.

To read some of Harper’s poems click here.

Nomination for Most Necessary Picture: Twelve Years a Slave

February 28, 2014I wish I could talk to my Great-Aunt Marie about the movie Twelve Years a Slave, but regrettably “Neenie” died when I was three. This spinster librarian from Detroit did, however, leave a legacy—a self-published book of family history. Written in 1957, this book documented my family’s years in Missouri in the 1800’s.

My parents ridiculed these books; giant unopened boxes of them filled our attic. When my father died, I finally brought one home and began to read it. To my shock, the very first line of the preface, written by Aunt Marie in 1957, tells me my ancestors “left a Virginia country environment where they were relieved of the drudgeries of workaday life by the labor of slaves…they were members of a society in which excellence in manners, morals, and religion were prerequisites.” In 1821, when Missouri became a slave state and offered land at $1.25 an acre, my ancestors migrated there.

I had always imagined these Missouri pioneer ancestors living in a house kind of like Little House on the Prairie. Never did I envision Ma and Pa and the kids with slaves out back, ‘relieving them of the drudgeries of workaday life.’ No one ever talked about our family history as slave-owners.

Aunt Marie says in her preface that the family letters, “too numerous to include, have been incorporated into dialogue. The conversations are necessarily fictitious, but the events are authentic. The story is a family diary with eighteen dramatic scenes.” In other words, old letters have been turned into the equivalent of bad 1957 church skits.

Each of these ‘dramatic scenes’ is scripted, with stage directions and settings written by Aunt Marie herself. These descriptions are the primary reason I wish that Aunt Marie and I could have watched and talked about Twelve Years a Slave together.

Here are a few of the lines Aunt Marie included to ‘set the stage’ for various scenes:

“Smiling blacks bear platters of food to the tables, while strains from banjo and guitar are heard from the rear.”

“Black folks … cluster around the well and weave in and out of the buildings, working, laughing, loafing.”

It wasn’t until I saw and reflected on Twelve Years a Slave and the history of cinematography about slavery that I realized where Aunt Marie’s images came from. They sprang, in technicolor, from her Hollywood-influenced mind. Hollywood has presented dozens of films with images just like the ones Aunt Marie described, showing slavery as a time when blacks smiled and laughed and loafed.

Now, thankfully, Hollywood offers a version of history more grounded in fact. Twelve Years a Slave takes its viewers into slavery, not through the eyes of the slave-owners, but through the eyes of Simon Northup, a freed black man from New York, stolen and enslaved. The film shows slavery as mundane, daily, ceaseless, violence and terror. Some African-Americans I know don’t want to see it, or loathed it. But as a white person, who doesn’t experience the daily relentlessness of racism, the physical intensity of the movie was transformative. Leaving the movie felt like stepping out of a virtual reality booth.

I suspect Aunt Marie would not want to have any of it. Her preferred view seemed to be that owning other human beings didn’t make a dent in one’s ‘excellence in manners, morals, and religion.’ Nor did ceasing to own other human beings involve any sense of repentance. As one ancestor wrote:

“I’m not going to let old John Brown or any confounded abolitionist steal my blacks… I shall free them myself. Freeing my servants will not be a financial loss to me. Most of the negroes I have were inherited. In return for their labor, I have given them food, shelter, clothing, medical care…and security in old age.”

When I utter judgment upon my ancestors, some white folks get upset with me for “imposing 21st century values” on 18th or 19th century people. Do we really have to talk about this? they all but groan.

I guess the primary reason I’m most grateful to Twelve Years a Slave is that it is a kind of family intervention. I was born in the latter part of the 21st century. Silences and lies about my family history were handed to me as intact and unbroken as the four sherbet dishes my mother gave me, which made the journey with my ancestors from Virginia to Missouri. If Aunt Marie, writing in 1957, had come to believe that owning other people was wrong, she never mentioned it. My liberal parents –civil rights activists–never saw reason to talk to us kids about this part of our family history. Like many white people, my siblings prefer not to talk about it now.

Though viciously brutal, the film’s truth-speaking is a relief. Finally! Because when do Americans, or families, sit down with each other and say, “Wow, that was us! We did that! What meaning should we make of that? How did we benefit? How were we hurt? How do we heal our nation? How should we live our lives now?”

Twelve Years A Slave may or may not win Oscars Sunday night. But its real value is in changed and enriched lives: lives of people like me who have new ways to talk about and challenge what Adrienne Rich called “the lies, secrets, and silences” which shroud our national and family and cinematic histories. If there were a category for “Most Necessary,” this would be, hands down, my choice for best picture.

Renew Your Membership

We invite you to join your fellow CLFers to renew your CLF membership and stewardship of the CLF for another year.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210