161: Resistance and Resilience

December 1, 2016Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:01:34 — 112.7MB)

Subscribe: More

Our guests, the Rev. Dr. Rebecca Parker and Donna Red Wing, talk about resistance and resilience in our personal lives, activist circles, and religious communities. This rich conversation explores both the outside and inside work that is needed, embodied intersectional living, and how spirituality enhances resiliency.

The VUU is hosted by Meg Riley, Joanna Fontaine Crawford, Aisha Hauser, Hank Peirce, and Alicia Forde, with production support provided by Terri Burnor. The VUU streams live on Thursdays at 11 am ET. This episode aired on December 1, 2016.

Note: The audio above has been slightly edited for a better listening experience. View the live original recording on YouTube.

Reps of God: Christian Triumphalism and the DIY Future of Unitarian Universalism

July 31, 2014LITE

The future of Unitarian Universalism does not lie in Christianity Lite any more than the future of Anheuser-Busch lies in Bud Light.

Oh, wait: Anheuser-Busch doesn’t have a future: it was bought out . . . by a European corporation that makes tasty beer.

In our consumerist religious landscape, the mainstream Christian denominations are scrambling to survive. I don’t doubt that they will do a fine job of brewing the new Christianity. A much better job than can Unitarian Universalism, except in very specific locations and boutiques.

Yes, as in beer, so in religion: the future for a small movement such as Unitarian Universalism lies not with Lite but with Hevy. The Godzilla of brewers, InBev, and the Presbyterians and United Church of Christ, and United Methodists et alia will do a fine job with the Lite. I think the future of Unitarian Universalism lies in micro-breweries. Boutique congregations, each with a recipe of their own.

Hevy

Keeping the church doors open after the Boomers are dead is the question. I’m not trying to be a controversialist. Like many ministers, I’m betting millions of dollars of other people’s money on a way to keep the church doors open into the future.

How?

A new book by Thomas Moore points to a possible way. In A Religion of One’s Own: A guide to Creating a Personal Spirituality in a Secular World, Moore makes a strong case for do-it-yourself (DIY) religion.

Aren’t Unitarian Universalist congregations uniquely suited to facilitate DIY?

We do well to draw a sharp line between the subjectivity of religious experience and the objectivity of a congregational, corporate life together. Where I get my personal religious jolt is up to me—Hinduism, Christianity, Buddhism, paganism, pantheism, atheism, all of the above . . . Up to me. DIY. Where I find my meaning is up to me.

Where I go for my religious, corporate, home is up to us.

For those who will be following Moore’s advice on DIY religion, one of the best homes is a Unitarian Universalist congregation . . . If . . . we can awaken to how big the tent must be.

This is the wisdom of the idea of covenant embedded so deeply in Unitarian tradition. “We need not think alike to live alike,” is the sentiment, even if no one famous ever actually said it.

Treating others as we would have them treat us—or, better, treating others as they would wish to be treated—isn’t so easy. The challenge is subjective: how the heck do we know how someone wishes to be treated?

Well, there is that thing called compassion.

In the Unitarian Universalist tradition we say that everyone has “inherent worth and dignity.” I would propose that this is how we treat our neighbor (and fellow congregants): as if that person has inherent worth and dignity. Then, we may go a step further and learn what that worthy and dignified person wants and needs.

But . . . What if I know better? I mean, really—what if I know darn well that I know better than my neighbor what my neighbor needs?

Party Foul! What you or me or anyone knows is always and only our subjectivity. Where you get your religious jolt. How you do your DIY religion.

You don’t know about your neighbor in the pew until you ask.

Furthermore, words matter. For example, for many people the word “family” does not have a warm and fuzzy feel to it. We do well to use care when we call a congregation a family.

And, no, “Amazing Grace” did not “save a wretch like me.” The apparatus that produced “Amazing Grace” enslaved my forebears for generations. And Jesus? His incarnation as “the body of Christ” in the church has been cruel to many of us. Not warm and fuzzy at all.

That’s two for instances. There are more . . . . More instances of oppression and exclusion.

Monarchy, Malarky

Unitarian minister John Dietrich, the founder of religious humanism, believed that a democratic society would create a democratic religion. After all, evidence suggests that religions reproduce in their structures and theologies the political and social structures in which they develop.

To see this, we only need go so far as a comparison of Judaism and Christianity. As anyone familiar with the Hebrew book of Judges or 1 Samuel knows, the ancient Hebrew tribes were highly suspicious of monarchy. Hebrew tradition reveals that mistrust, even though the Hebrews flirted with monarchy in the time of King David and the subsequent temple at Jerusalem. (Speaking of disasters!)

Christianity, the child of Judaism, early fell in thrall to the structures and attitudes of the Roman empire. The bowing and hierarchy that is so much a part of European monarchy and much of Christian worship is foreign to the Jewish tradition. And it feels less and less OK to many of us living in liberal democracies.

John Dietrich, and other humanists of the 1930s, thought that the monarchical model of the Christian tradition would disappear in the democratic age.

And it has, to a great extent. If it hadn’t, there wouldn’t be any DIY religion.

The only religion that will ever make sense to you—when you’re not going along to get along—is that one that you have arrived at by choice, in your own thoughts and your own integrity.

Religious experience is subjective. Personal. Forcing it on others is a party foul and a Golden Rule violation.

The Short Shelf Life of European Christianity

Reflect on this: of the people in the United States today, how many had Christianity forced upon their forebears?

Answer: Nearly everyone who lived outside of the Mediterranean basin in the 300-500s CE.

Reflect on this: how many of those who became Christian outside of the Mediterranean basin had a choice in the matter?

Did the British? Did the Irish or Welsh? Did the Germans or Norwegians or Poles or Swedes or Swiss or . . . ?

Nope. Most of the population in Europe had no choice. The choice was made for them by the ruling elites.

How about the Africans brought forcibly into the Western Hemisphere?

Nope.

The native peoples of the Western Hemisphere?

Nope. No choice.

For millions upon millions of people, Christianity was not a choice. Should we wonder then that so many of their children abandon an imposed religion as soon as secular governments and social expectations allow?

For most of us living in the Western Hemisphere, Christianity is an overlay, not a deep tradition. A Mediterranean imposition, not a value system that matches the flora and fauna and mores that most of us were born into.

Malcolm X taught this, but his words have not been heeded.

Pagans in the UU movement have been pointing this out for some time. In my congregation, the Jews, Hindus, pagans, and Muslims and atheists and others and more cry out . . . when will we be free?

When will we build that land, that inclusive place that is actually inclusive, the includes not just Christians but others?

Despite Liberation Theology, the Social Gospel, and the Emergent Church, Christian ritual and theology is the theology and ritual of oppression for many of us.

Yes, those lively spirituals subvert the dominant paradigm and reveal the ugly truth of oppression. But isn’t it time we sing a new freedom song? Isn’t it time we subvert the most dominant of paradigms—Christianity itself?

And then there is the inclusion of Christians too.

Think hevy. Think micro-brew. And DIY.

What if Unitarian Universalist congregations were actually, truly, a big tent where all are welcome, not just the Christians? Not just the humanists?

Can I have an “ameen”?

Some of us will not worship any prophet or any god, no matter what the cost. Where might we find a home?

How about a really big tent for the future?

Photo credit: The copyright on this image is owned by Simon Johnston and is licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.

Simple Prayer, Profound Meditation

April 18, 2014please… please.. please…please.

I whispered the words softly, quietly.

As I stood in the bridal waiting room at the back of the church, ten years ago, ready to step out to a church filled with family and friends where my soon-to-be-husband was standing at the altar, I breathed those simple words.

Please. Please. Please.

I chanted the words silently, but strongly.

The words were half prayer, holding a sea of emotions, hopes, and fears. Not a prayer for divine intervention, but rather an appeal for serenity, strength, and mindfulness. As one of the most basic religious exercises, prayer has been shown to improve calmness, by strengthening brain regions that foster compassion and by calming brain regions linked to fear and anger.

And the words were also half mantra meditation, helping to calm my mind – my monkey mind, as Buddhists call it. Derived from the Sanskit work for “mind tool,” mantra meditation involves chanting a single word or phrase in order to focus the mind. Eventually the mind focuses more on the rhythm of the words, and less on the words themselves.

Please.

Please don’t let me trip walking down the aisle.

Please don’t let me break into uncontrollable sobbing.

Please let my husband feel as sure about this day as I am.

Please.

Please let this be more than just the wedding I dreamed of, but also the marriage that we both deserve.

Please make us family.

Please give me strength.

Please give us strength.

Please.

Please…such a simple word, but a profound word. As I chanted that simple word in sighs and whispers, the clouds of nervousness, anxiety, and worry parted. The rays of strength, confidence, hopefulness, and faith shone down.

Please…the holiest of prayers because what follows can contain the depths of our heart. The Spirit knows what follows that little word please. The Divine knows the unspoken that lies hidden in sighs and tears and deep breaths, even if we don’t.

Please...my favorite prayer, my truest prayer.

And thank you. The only response that ever seems appropriate for all that the Spirit bestows.

**********

How do you pray? What is your favorite prayer?

**********

This post originally appeared on the author’s website here.

What Bowling Taught Me About Patience

January 31, 2014A couple of week’s ago, on a cold Chicago afternoon, after being cooped up for most of the week, my husband and I looked at each other and said, “Let’s go bowling.”

Now, nothing says wholesome family fun quite like putting on some smelly communal shoes and listening to drunk men swear at the football game, but after being cooped up in the house for more of the week, we were just a little bit desperate.

Matt and Jack have gone bowling together a few times, but this was the first time that Teddy had been bowling. After trying on three (three!) different pairs of shoes, convincing him that the bowling ball that looked like Darth Maul was too heavy for him (he’s just a tiny bit obsessed with Star Wars), and showing him how to put his almost-four-year-old fingers in the ball and roll it down the lane, he was ready to go.

“Self! Self!” he stubbornly said in true Teddy fashion.

He walked to the line holding the ball with both hands and I have never been more certain that a trip to the ER for a broken toe would be in our near future. (By the grace of God, he made it out of the bowling alley with all ten toes intact.)

For ten frames, Teddy grabbed his ball, stepped up to the line, and heaved the ball as hard as he could down the lane. Most of the time, he rolled the ball right into one of the bumpers and it would sloooooowwwly bounce its way down the lane. On each of his rolls, the ball moved so slowly, in fact, that I was pretty sure that it wouldn’t make it to the pins. And, more than a few times, Matt and I exchanged a look that said, “Which one of us is going to ask the surly desk attendant for help when the ball stops in the middle of the lane?” (Fortunately, we never had to answer that question, but for the record, it would have been him.)

On every one of Teddy’s turns the ball moved at a snail’s pace, barely moving down the lane until, finally, it would make it to the pins and maybe even hit down a few. As one of THE most impatient people on the planet, I found the delay to be a bit unsettling at first. Waiting for the ball to plod down the lane, I felt nervous, jittery, and antsy.

But, after a few frames, I realized that what I was feeling wasn’t actually impatience; it was fear. Fear that the ball would never make it, fear that we’d have to ask for help from the surly man at the front desk, fear that Teddy would end up in a tantrumy heap of tears.

But, after a few frames, I realized that the ball would eventually make it to the pins even though it looked like it might stop moving at any moment. And with the fear of not making it subsiding, the waiting actually became the best part of it all. Because in the waiting, I had time to soak it all in. I could watch Teddy’s eyes light up as the ball moved down the lane, I could steal a few glances at my husband, and I watch my older son add up the scores on the screen.

Once the fear of never became the confidence of eventually, I was able to look at the waiting and the slowness in a whole new light.

And I wondered: How many other times have I mistaken fear for impatience? Fear of the never or the always. Fear of the falling and failing. Fear of dead ends and asking for help. Fear that without the end, the means just don’t matter.

And in this fast-paced, frenzy to get something or do something or hit the target, how much has gone unnoticed and how much enjoyment have I missed in the slow-moving journey?

I’ve been struggling a lot with impatience lately, wanting things to happen now, now, now. But I am realizing that this need for things to happen on my timetable is less about fulfillment and satisfaction, and far more about fear. Fear of losing control, fear that I will never make it, fear that I am somehow lacking just as I am and right where I am, fear that I won’t be satisfied until the pins are knocked down so to speak.

We tell ourselves that when the pins are knocked down, then we’ll be happy. When we get married, when we have a baby, when the kids are in school, when the kids are out of the house, when we get the job, when we get the promotion, when we are out of debt, when we buy a house, when we get an agent, when we get published, when we receive this award, when we land that sales account, when…, when…, when…then we’ll be happy. And all the while, the ball is moving slooooowwwwly down the lane and there is so much going on while it rolls if only we’d just notice.

The ball moves slowly, more slowly than we’d like, many times. And we wait and we wait and we wait, growing increasingly tired of all the waiting and more fearful that the ball might actually stop. And in all of that fear, we miss it. We miss the twinkly eyes and the emotions, the bouncing back and forth and the graceful movement to it all, the sights and sounds and people and various goings-on that are actually a really big deal if we’d just stop focusing so much on those damn pins at the end of our lane and trust that the ball will eventually get there.

After bowling for a few hours last Sunday afternoon, and watching the ball move slowly down the lane, I realized a few things. I realized that the ball will slowly, eventually, finally reach the pins; it just takes a little longer sometimes. I realized that if the ball does stop, you can always ask for help (even if you have to ask the surly man behind the desk), get a new ball, and roll again. And, most importantly, I realized that there is so much good stuff going on while we wait for whatever it is that we’re waiting for.

So take your time. Pay attention. Enjoy the journey.

And know that, even when the ball moves slower than we ever thought possible, that at least the pins are happy for few extra moments of peace.

This post originally appeared on the author’s website at www.christineorgan.com.

On Building Bridges

January 3, 2014

“We build too many walls and not enough bridges.”

Isaac Newton

About five years ago, I sat in church one cold and dreary Sunday morning while our pastor, Jennifer, talked about bridges. I came into church that morning a little lost, a little frustrated, and utterly exhausted. I didn’t really want to be there and I had been feeling so beaten down by life that I seriously doubted whether words of spiritual advice would make any difference whatsoever.

Nonetheless, I sat in that small church, distracted, and I listened to her talk about shoveling sidewalks and neighborhood parties and wide nets. She talked about the sacred act of building and strengthening bridges, about maintaining and honoring those bridges, and she then issued a challenge to us to become bridge-builders ourselves.

At the time, her words fell on a weary soul and an exhausted body. With a two year old at home and mountains of stress, I wasn’t looking to build bridges; I was just hoping to survive the day and maybe take a nap. Yet, somehow her words rang true and they stuck with me ever since.

On some intrinsic level, I think that we are all called – whether by God, some higher power, or the human condition – to be bridge-builders. We are naturally driven, I suspect, in some deep primal way, to want to connect, to build bridges – in our families, social circles, communities, and workplaces; with the natural world and the spiritual world; with others and even within ourselves.

But, what does it mean to be bridge-builders?

While we are called – compelled even – to be bridge-builders, it is not always an easy task. In fact, I think that it just might be one of the hardest things that we, as imperfect and ego-driven humans, are asked to do. Bridge-building is awkward and daunting and painful; it is clumsy and uncertain and utterly exhausting. Bridge-building means uncomfortable conversations and bruised egos and being the first one to say “I’m sorry” or “I love you” or “I was wrong.” And bridge-building requires a healthy dose of faith, copious amounts of forgiveness, and an infinite amount of grace.

I would be lying if I didn’t say that my ego and heart haven’t ached just a little bit when, after introducing some friends, they prefer each other’s company to my own. I would be lying if I didn’t say that doesn’t take frequent reminders to check-in with extended family and friends during those times when life’s obligations leave little room for anything beyond carpools and homework, conference calls and emails, paying bills and folding laundry. I would be lying if I didn’t say that I have to constantly fight the urge to wear my Facebook mask, to present a Pinterest-worthy picture of my life to the world, to pretend that I’m not constantly second-guessing myself. And I would be lying if I didn’t say that there have been times when the time and energy spent building bridges hasn’t left me feeling scared, inadequate, and completely drained.

There is a natural tendency, I suppose, to preserve, protect, defend, and maintain the status quo. We get busy and beaten down with the day-to-day stresses and the curveballs that life throws at us, and sometimes bridge-building just seems like too much work and a colossal waste of time.

But bridges aren’t built when we stand our ground and stay in our comfort zone; they aren’t built when we focus on relationship maintenance, rather than relationship sustenance. Bridges aren’t built in the masks or by pretending that we aren’t scared and confused. Bridges aren’t built when we snicker at the expense of another, when we think in terms of “us-them” and “the other,” or when we focus all they ways we are different.

No, bridges are not built this way.

Bridges are built when we cast a wide net, when we make the effort, when we are radically inclusive. Bridges are built when we ask questions and take the time to listen to the answers. Bridges are built when we lay ourselves bare and stumble through the muck; when we make an intentional and difficult decision to forgive; when we focus on our shared and common human condition. Bridges are built when we step into the heart and mind of someone else; they are built with a single phone call or email, with a tender touch, with an open mind and a generous heart.

Bridge-building is hard, hard work. But bridge-building is good work, beautiful work, essential work. Bridge-building is holy human work.

There are bridge-builders all around us, and we can be bridge-builders ourselves, whether we know it or not. With her prophetic words about neighborhood parties and shoveling sidewalks and taking the first step, Pastor Jen built more bridges for me than she could possibly know. And for that I am eternally grateful and continually inspired. We have both since moved away from that church community in Chicago, me to the suburbs and she to California and then Virginia. But I have no doubt that she has been continuing to build bridges along the way. Because once a bridge-builder, always a bridge-builder.

Who are the bridge-builders in your life?

Beauty of the Season? Really?

December 20, 2013

I did not plan to write this post. In fact, I had intended to write something very, very different.

Given that this weekend marks the winter solstice, I had wanted to write something poignant and insightful about the beauty of the season. I wanted to write about the joys that winter brings, about sledding and snow angels and hot chocolate. I had planned to write something spiritual about the way that winter’s long nights give us a chance to rest and reflect. I wanted to write something optimistic about all of the warmth that lingers in the chilly winter, about growth and rebirth, about the the changing seasons as a reminder that everything is temporary.

I wanted to write about these things. I had planned to write about these things, had hoped to write about these things.

But I just couldn’t do it.

Because, honestly, I FREAKING HATE WINTER.

Try as I might to dig deep spiritually and see all the good that winter offers, I just can’t seem to do it. In fact, I hate almost everything about winter. I hate the snow and ice and frigid temperatures. I hate the bulky sweaters and heavy boots and the way my hands are always cold. I hate the muddy puddles that pool by the door. I hate that it’s dark at 4:30 in the afternoon. I hate shoveling. And I hate that it takes longer to get my kids dressed in their winter gear – coats, snowpants, hats, and mittens – than it does to actually get where we are going.

The optimist in me wants to learn to love all of life’s seasons, even the cold and dark ones. And the UU in me is trying desperately to “respect the interdependent web” and enjoy winter for its role in that cycle of connectedness. Yet despite my spiritual, optimistic, glass-is-half-full attempts to appreciate winter, the simple truth is that I HATE WINTER and I’m only hoping to survive the next few months.

I want to be more tolerant of winter’s harsh personality. I want to see God’s beauty in the dormant bud as much as in the flowering bloom. I want to be stronger, more resilient to the bitter and biting cold. I want to be more flexible to the changing seasons on the calendar and in life.

But some days, it is just so hard to be tolerant, to see the beauty, to be resilient. Some days it is really hard not to be consumed by the darkness. Sometimes it is almost impossible not to rage against change, almost impossible not to scream “ENOUGH ALREADY! I CAN’T TAKE ANYMORE!” (By now you’ve probably figured out that I’m not just talking about winter here.)

It feels selfish and self-indulgent to wallow in my disdain for what amounts to a minor inconvenience, a slight discomfort. It seems short-sighted and pessimistic to focus on the darkness and the harsh conditions. It feels feeble and gloomy to wallow in the ugliness, desperate and ungrateful to long for lighter, warmer days.

But does loving life mean that we have to hide our disdain for the colder times? Does respecting the web of connection mean that we have to delight in all aspects of a network so complex and delicate that we cannot possibly make sense of it all? And does the cultivation of gratitude mean that we are prohibited from yearning for better, brighter days?

Hardly.

Maybe tolerance doesn’t come from looking with favor on every hassle and indiscretion, but rather through an admission of our unhappiness and a willingness to move through it. Maybe resilience and flexibility don’t ask that we greet bleak conditions with delight, but simply that we acknowledge the discomfort with truth and kindness.

And maybe Grace isn’t found in pretending the dark and cold times aren’t exactly what they are – hard and difficult. Maybe Grace comes from a simple acknowledgement that “THIS SUCKS,” followed by a deep breath and the inherent understanding that, for better or worse, this too shall pass.

This article originally appeared on the author’s website.

The Language of Faith

November 1, 2013

Source: Google Images Creative Commons

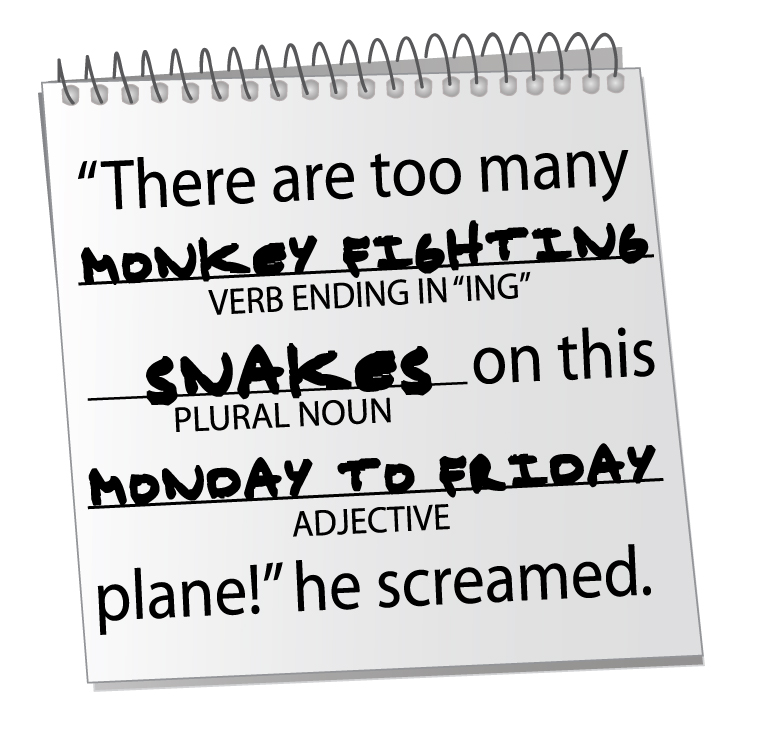

Last Sunday, while out to lunch with my husband and two young kids, we passed the time waiting for our food by playing Mad Libs. As you might remember, Mad Libs is a word game where one player asks another player to provide a particular kind of word – noun, verb, adjective, etc. – to fill in the blanks of a story. After the words are provided, randomly and without context, the other player reads the funny and often nonsensical story aloud.

If you have ever played Mad Libs, you know just how important grammar and semantics are to the art of storytelling. You also realize just how important words and context are to communication and understanding.

Words are, obviously, incredibly powerful tools. We use words to communicate, to connect, to explain, to inform, and to educate. But words have significant limitations, as well. Unfortunately, all too often words are used as a weapon instead of a tool. We use words to restrict instead of expand, to assume instead of discover.

Ironically, we often try to use language to define those things that are undefinable. We try to explain the inexplicable with rational, but overly simplistic, definitions. We fit people into our prepackaged labels –believer, nonbeliever, Christian, Jew, Muslim, atheist, humanist, idealist, pacifist, liberal, or conservative – and we try to make sense of this crazy, nonsensical, Mad Libs-like world with assumptions and categories.

But when it comes to the Big Questions, to matters of the Heart and the Spirit, there are no definitions. There are no labels. There are no prepackaged boxes.

Quite simply, language fails us when it comes to matters of the Spirit. God (I use the word “God” knowing that the word itself has its own limitations) comes in many names and is experienced in many ways. God and all things Spiritual, by their very nature, are unknowable and personal; they are felt with the heart and cannot always be adequately explained with words.

But, being the intelligent humans that we are, we try to explain that which is deeply felt with words, explanations, and sound bites. And, as a result, any inherent commonality to our human spirit gets lost, the beautiful complexity of differences gets diluted. The words – and labels – that we use become more important than the ideas.

So much division and dissention is created and exacerbated by the labels and linguistic limitations that we put on matters of faith and spiritual belief – concepts that are, quite frankly, too big to fit into any label or verbal representation.

Perhaps, we need to focus less on the words of faith and more on the language of faith. Perhaps we need to stop getting lost in the semantics of God and, instead, learn the languages of God – ones that are spoken and heard in a number of ways.

Music has always been my language of God. I love to sing (off-key) and can clumsily tap away a few songs on the piano, but I am far from what you would call “musical.” Yet music has always been a profoundly moving spiritual experience for me. Whether I’m swaying to a church choir singing “Amazing Grace,” listening to Bon Iver on my iPod, singing along to Bob Dylan in the car, or dancing like crazy with my kids in the kitchen, few things have the power to move me like music. Music creates an internal communication with the Spirit that washes my soul clean, as if I have stepped into a warm shower with the lyrics and melody rinsing away the grit and grime of everyday life.

Spiritual language can be found in any number of ways. My grandpa spoke the language of God through his generous hospitality. It was nearly impossible not to feel like THE most important person in the world when he greeted you. Others feel the language of God through the earth and nature. Gardening, for my paternal grandma, was so much more than a household chore, it was a spiritual practice unto itself. With her fingernails soiled and her hands calloused, as she tended and cultivated, she spoke a spiritual language that only her soul understood, that only her Spirit could appreciate.

Some people speak God’s language through art or poetry, photography or painting, teaching children or caring for animals, caring for the sick or sharing a meal with friends. Shauna Neiquist wrote in Bread and Wine, “When the table is full, heavy with platters, wine glasses scattered, napkins twisted and crumpled, folks askew, dessert plates scattered with crumbs and icing, candles burning low – it’s in those moments that I feel a deep sense of God’s presence and happiness. I feel honored to create a place around my table, a place for laughing and crying, for being seen and heard, for telling stories and creating memories.”

Let’s face it, we live in a chaotic world, where the unimaginable meets the incomprehensive, and devastating realities mix with everyday miracles. We want to make sense of it all. Of course, we do. In our well-intentioned, but misguided, attempts to explain, understand, and communicate, we look to definitions and labels. We rely on assumptions and suppositions, and we look to linguistic placeholders to meet the expansive scope of faith, God, and the Spirit.

We try to define the indefinable.

But maybe if we spend a little less time focusing on definitions of God and labels of faith, and instead focused on feeling the complex languages of God, maybe then we could gain a better understanding of each other and ourselves.

Arguing Over the Light

June 27, 2013All religions, all this singing, one song. Rumi

1.

A poet I met once,

Leslie Scalapino, said

“stay in continual

conceptual rebellion.”

She thought we must

“re-form” our minds,

“make it new, every day,”

as Pound put it, or fall

for the snake oil routines

of all the drummers and

askers around us.

“No” to con-vention,

she thought, checking

out of the general meeting

where the selling

is done is “yes” to life.

2.

Seeing things as they are,

Nagarjuna said, is the way

to wisdom. Finding first causes,

hooks on which to hang a hat,

is a fool’s game and leads

to distinctions–this is

not that. And on and on.

Until there’s only suffering.

We like listening

to the snake oil salesmen

throwing out distinctions

and offering attachments.

It’s entertaining.

It’s death.

3.

When an old man was asked

what held the earth up, he

said, “It sits on a turtle.”

And under the turtle?

“Another turtle.” And

under that one? “It’s turtles

all the way down,” the man

laughed. And it is. Turtles.

It’s turtles all the way down;

turtles all the way up;

turtles in every direction,

and turtles because there

is no direction. It’s turtles,

and we, too, are turtles.

Or one turtle.

Or snake oil.

Or light.

Softballing with Spinoza

May 2, 2013If a triangle could speak, it would say . . . that God is eminently triangular, while a circle would say that the divine nature is eminently circular. Thus each would ascribe to God its own attributes, would assume itself to be like God, and look on everything else as ill-shaped. ~ Baruch Spinoza

I remember going home for the first break of my first semester in college. We, my mother, father, and I, were driving along the Mississippi River in Missouri, along the New Madrid Fault Line, traveling from our family farm in the southern part of Illinois to visit some relatives near Memphis, Tennessee for Thanksgiving. I, eighteen years old, was driving.

As I drove, I was paraphrasing the above observation of Spinoza, which I had just been studying in an intro to philosophy class at the community college I was attending. The community college was only twelve miles from our family farm, but a world away for me. My philosophy class was taught by the first openly gay man (“open” is a flexible term when applied to the attitudes of the 1970s), and my mind was racing with new ideas.

Spinoza’s argument seemed so elegant to me; so irrefutably true: We are not created in God’s image, but rather we create our gods in ours. If triangles could think, they would consider themselves created in the very image of god. If ants could think–and who says they can’t?–they would create an ant god (and who says they don’t?).

Neither my mother nor my father had any idea what I was talking about. How would a triangle think? Why would an ant think about god? Those things didn’t make “good horse sense.”

Both of my parents grew up in rural southern Illinois. They attended one-room schools–not the bucolic one-room school houses of US nostalgia, but places where the overworked teachers had, at best, a full year of college education and had to contend with whatever learning disabilities and behavioral disorders appeared among the in-bred hill country population. The teachers were generally paid in chickens, eggs, and firewood.

Consequently, both of my parents were nearly illiterate. Abstract thought did not come easily to them. As a matter of fact, the only negative statement I ever heard from either of them concerning orthodox Protestant Christianity was spoken decades later by my father, when the subject of the Resurrection came up. Out of the hearing of my mother, he said, “It just don’t seem possible, does it?”

I answered gently, “No. It doesn’t seem possible.” That’s as close to mystery as my father ever got.

On that day driving along the New Madrid Fault, I realized that Spinoza could not speak to my parents. And I discovered something else: I had the power to destroy the faith of poor, oppressed people such as my parents who had nothing else to fall back on. I stopped the argument when I was eighteen, and I have never argued religion again.

The chance to think abstractly, to pursue truth wherever it leads, is a powerful gift. A privilege. As with all power and privilege, it must be used responsibly and humbly.

Bodhidharma Proposes to the Wall

April 11, 2013Bodhidharma sat there,

they say, nine years, but

you know how they talk.

Bodhidharma there to

wonder why he thinks

this could be different

from that. To wonder

what it might have been

we think differentiates

one depth from another.

Isn’t that the secret?

Bodhidharma said

to the wall. You

won’t know your

self until you stop

deceiving yourself,

Bodhidharma said

to the wall. Sounds

sound, until the self-

referentials begin

to sink in. Then

words mumble. Slow.

Into the nothing that is

the walls around.

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210