The Hungry Coat

May 17, 2017A Creative Life

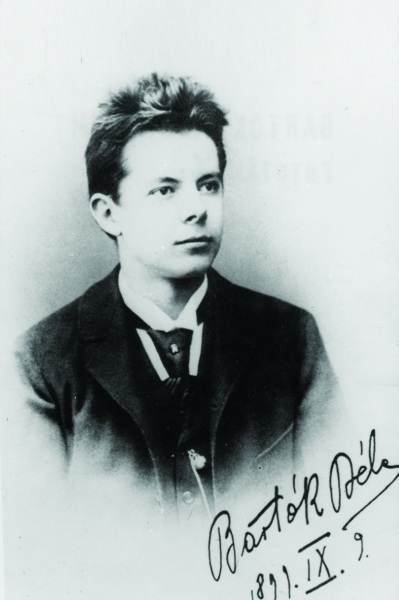

April 7, 2017Béla Bartók was a Hungarian pianist and composer who added a great deal to our world through his creativity. He started playing piano as a tiny child, and knew 40 songs by the time he was four—and gave his first public recital , including an original composition he’d written two year earlier, when he was eleven.

Bartók went on to become a famous composer who not only wrote his own music, but also went out around the countryside gathering folk music, which he often worked into his compositions. While he was collecting music from the Székely people in Transylvania he learned about Unitarianism.

He liked the idea of a creative religion that was less about following rules and more about connecting with all aspects of life. He eventually joined a Unitarian church in Hungary, and attended with his son.

With the rise of a fascist government in Hungary and the approach of the Second World War, Bartók fled to the United States. He was safe there, but felt lonely and disconnected from his homeland, and it was hard for him to continue to write music. But when he was diagnosed with leukemia and knew that he did not have very long to live, his creative energy returned in a burst and his last compositions are often considered his greatest.

To learn more about Bartók and listen to some of his music, visit the NPR story, “Béla Bartók: Finding a Voice Through Folk Music”

Music: Béla – Evening in the village

Here is one of Bartók’s compositions, titled “Evening in the Village.” The tune comes from a folksong, which is called the “ancient Székely anthem.” The pictures in the video were almost all taken in Transylvania, where Bartók discovered Unitarianism. (The one with the gate was taken in Máriabesnyő, a famous shrine in the outskirts of Budapest.)

Waiting is Not Easy!

November 30, 2016

Here is another story for the season, one that is very much about waiting. This is the story of a special child. Like every child, his parents waited eagerly for his birth. More than 2,000 years later, Christians as well as many Unitarian Universalists celebrate this birth at Christmas.

The Father of Christmas

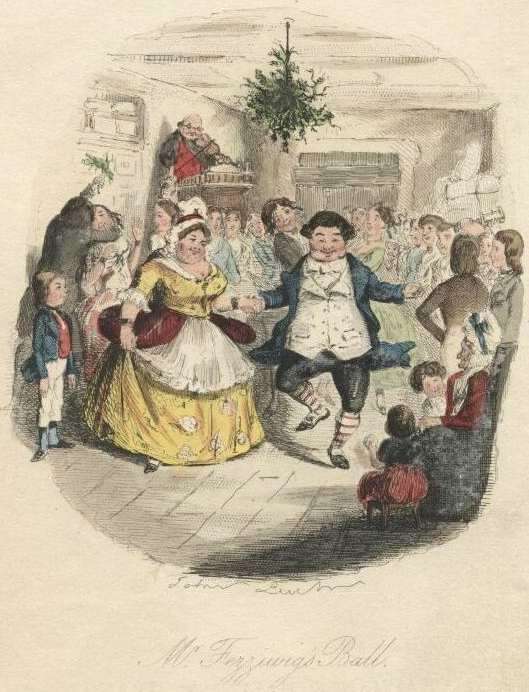

November 30, 2016This month we celebrate Charles Dickens, British Unitarian, and author of A Christmas Carol. When Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol in 1843, many Christmas traditions had almost died out, and the holiday was hardly celebrated. England was becoming more and more industrial, and people leaving farms to work in factories had left their old customs behind.

But the story, which was wildly popular, brought enthusiasm back to the cities for practices like singing Christmas carols and feasting on special foods. The picture of the Cratchit family celebrating their Christmas together inspired people to find a way to celebrate Christmas in the cities, and the change of heart which comes to Ebeneezer Scrooge reminded people that Christmas was traditionally a time when the wealthy folk shared with the poorer people.

In fact, Dickens was very concerned with the conditions of poor people in England at a time when the gap between the rich and the poor was getting wider and wider. Many of his books deal with this theme, and he became a Unitarian because, as he said, they “would do something for human improvement if they could; and practice charity and toleration.”

Interested in learning more about Charles Dickens, our religious ancestor? Here are a few additional resources:

A 2005 UU World article, “Ebenezer Scrooge’s Conversion,” by Michael Timko, describes how Charles Dickens’s story, A Christmas Carol, exemplified 19th-century Unitarianism.

In the Tapestry of Faith children’s religious education curriculum Windows and Mirrors, Session 13 (Images of Injustice) addresses Charles Dickens, his work and his dedication to improving the lives of the poorest English workers and their families. From the introduction to the lesson:

As Unitarian Universalists, we do not turn away from noticing the gaps that separate “haves” from “have nots.” To work against inequity, we know we first have to see it. Unitarian Charles Dickens saw it. Born poor, he later earned a living as a writer and joined a more comfortable economic class. Dickens used colorful character portraits and complex, often humorous plots, to expose tragic inequities in 19th-century British society. He showed that people at opposite ends of an economic spectrum belong to the same “we,” united by our common humanity and destiny—a lesson which resounds with our contemporary Unitarian Universalist Principles.

The website Charles Dickens online has well as the Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography offer biographical information and many other resources.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210