The Problem with Evil

June 21, 2012It is a strong word, evil… and one those of us of Liberal Faith have not always engaged well. I mean the word… people of Liberal Faith have often come into contact with evil, we just have trouble calling it that.

often come into contact with evil, we just have trouble calling it that.

This week, I am in Phoenix, attending the Justice General Assembly of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. Two years ago, when other denominations and institutions were being encouraged to boycott Arizona over the passage of the anti-immigration law known as SB-1070, our denomination was invited by both our Phoenix congregations and by our Arizona Allies for immigration reform to come to Arizona. We were invited to forgo much of our normal General Assembly business, and to come and allow their stories of facing the evils of our nation’s and this state’s current immigration policy to transform us. We were invited to stand in solidarity with them. We were invited to learn, grow, and transform with them.

And yet, in our desire to be present and to “make a difference” in this time of deportations and family separations and the dehumanization of being forced to prove your citizenship status because of your skin color, we of liberal faith who have come to Arizona this week also have the potential to cause harm, and to commit acts that would be viewed by some as evil… perhaps not in their intent, but certainly in their effect.

I believe in the ultimate unity of all things. That all of us are part of the greatest reality which I define with the name God. For me, God is all and is in all, the rocks and the trees, the birds and the bees, the smallest atom and the largest galaxy. All interconnected and interdependent, we are all a part of God. All of the divisions that we humans see or hope to see around us are coping mechanisms that we limited creatures have created to deal with an unlimited divine reality.

One of those coping mechanisms is the imagined division of good and evil. I am not saying that good and evil are imaginary, but rather that the division between them is. At their core, good and evil are human valuations of acts, intents, and events that happen within the wholeness that I call God. More than perception, naming something as “good” or as “evil” has a lot more to do with the values of the person doing the naming than it does being an inherent aspect of the thing being so judged.

Let me take immigration as an example. I believe that current federal and many state policies regarding immigration to be evil. I believe that the enforcement of immigration policies here in Maricopa County, Arizona, and in many parts of this state, is evil. And, that belief says a lot more about me than it does about the events here in Arizona themselves… or at least it says a lot more about the values that I hold at the center of my life.

I find immigration policy and enforcement, as it is currently being practiced in Arizona and beyond, to be contrary to by belief in the inherent worth and dignity of every person. I believe that the arbitrary border of the United States forgets that this land was unjustly taken from indigenous peoples, some of which are my ancestors. I believe that this nation depends upon the labor of many who are undocumented, and not recognizing them and regularizing their immigration status is a new defacto form of slavery. I believe that human rights are being violated every day in the name of border enforcement. I believe that people are not being given the democratic rights to representation and self-determination.

And so, I believe that the current form of immigration policy and enforcement is evil. I believe that because my principles, values, and religious faith call me to that belief… and as such I am responsible to do whatever I can, in good conscience, to bring an end to that evil.

You see, neither good nor evil have a metaphysical reality. I do not accept that there is some metaphysical being who embodies evil and brings it into the world. I believe that naming a metaphysical nature to evil (like the devil) is a way for humans to name something as evil without having to take personal responsibility for working to end that evil. A metaphysical center for either good or evil has the effect of disempowering humanity for their responsibility for what is good, and for what is evil in the world.

Because each and every one of us has tremendous capacity for good, and for evil. And, because not all human beings agree on our foundational values, principles, and religious faith, many of the things I view as supporting good are viewed by someone else as supporting evil. There are those here in Arizona who believe that all of these religious liberals coming to stand with and bear witness with our local allies is a form of evil. We each also have the capacity to commit acts that might be evil in our own eyes, were we to see them clearly.

An example of such would be if we religious liberals came to Arizona like “saviors” and attempted to paternalistically take leadership in this long running struggle, instead of coming to learn from those who have been in this struggle for so long. We are here at their invitation, to learn from them and to stand with them. If we were to try and engage this struggle in any other way, we would be in danger of committing another evil, in our own eyes as well as theirs.

Evil exists, and it is in us. We human beings create it, even when we sometimes don’t intend to… and what we define as evil is one of the clearest expressions of what we value ourselves.

Yours in Faith,

Rev. David

Through the Roof

June 18, 2012There’s a transformational story in the fifth chapter of Luke (verses 17-26). Jesus is teaching in a home (probably an upscale home, given the tile roof), and there are many people from Galilee, Judea, and Jerusalem. Even the scribes and Pharisees were there. They were always checking up on Jesus to make sure he wasn’t causing too much trouble. It was standing room only, and the door was blocked. A few guys brought a friend, who was paralyzed, in his bed to be healed, but the crowd was so big that they couldn’t get through the door to see Jesus. The people didn’t even make way to let these guys through. Maybe you’ve been to this church where newcomers weren’t even noticed, and where the members stand at the entrance talking to each other?

Not being deterred, these men actually went up to the roof and lowered their paralyzed friend in his bed through the ceiling tiles to see Jesus. When Jesus saw their faith, he said, “Your sins are forgiven.” Of course, as they always did, the scribes and Pharisees jumped right on that one and challenged Jesus, saying, “Who is this who speaks blasphemy…only God can forgive sins.” Jesus answered, “Why do you question in your hearts? Which is easier to say, ‘Your sins are forgiven,’ or to say, ‘Rise and walk.’ I’m going to prove to you that the son of man has the authority to forgive sins.”

The translation “son of man,” “barnash” in Aramaic, does not necessarily mean the “son of God.” It is not exclusively a reference to divinity, but refers to humanity. Jesus isn’t talking about himself as a divine arbiter. He is saying, “I’m going to prove to you that mere mortals can also offer forgiveness,” which he had just done.

Back to the story, Jesus turned to the man in the bed and said, “Rise, pick up your bed, and go home.” And that’s just what the man did. Everyone there was amazed and said, “We have seen extraordinary things today.”

Suspend for a minute the idea that this was a literal healing. I believe that to take everything in the Bible literally actually limits its potential and power. When Thomas Jefferson cut the miracles out of his Bible, I think he missed the point. He was taking these miracles too literally and wasn’t open to the power of metaphor.

If we allow this story to be metaphorical, then it is even more instructive to us today—timeless in its power. Too often the members of congregations, ordinary people of all walks of life, sit around and do their own thing. This is the status quo. We do things the way they’ve always been done, and sometimes forget that there are others who are excluded and cannot do the things that we take for granted and do on a regular basis. The paralyzed man wanted a change. He wanted transformation in his life. His friends wanted it for them. Perhaps this was just an intervention. But they couldn’t even get through the door. They couldn’t even be part of the status quo. Most people would have just given up, but these guys decided to come through the roof. They changed the status quo by changing the rules. In the end, it wasn’t Jesus who healed the paralyzed man. It was his own faith. He came to that synagogue to be transformed. Jesus just said, “Your faith is strong. Your sins are forgiven.” Sin doesn’t always mean that we’ve done something bad, just that we’ve “missed the mark.” Whatever this man had tried to heal his paralysis hadn’t worked. Jesus just presented the obvious. “Get up. Walk.” Too often when we are stuck, stifled, and paralyzed in life, we forget to do the obvious.

A Personal Relationship with God

June 7, 2012The aspect of my personal faith that seems to bring about the most confusion in friends and colleagues is that I believe I have a deep and abiding personal relationship with a God that is incapable of knowing that I even exist.

abiding personal relationship with a God that is incapable of knowing that I even exist.

I find that the confusion about this theological point rests not only with those more theologically conservative than I, but also with those more theologically liberal or secular than I. More conservative ministers and theologians are confused by my claim that I can have a personal relationship with a non-personal God. My more liberal and secular colleagues question the same thing, but with the opposite emphasis.

While I have talked about this in other articles (including here), I believe that there is no division in God, that every moment of every day we are intimately involved with God; in a flight of birds, in a breath of wind, in a cab driver who cuts us off, in a moment on the Zen cushions… all one, all God. We are a part of God, and nothing can be more intimate than this. God is a holy spirit that is intimately involved in all things, and we are intimately involved in the part of God we can touch and sense.

However, God does not, in any personal way, know that I exist as an individual. I wonder whether God is even capable of “knowing” in any human sense. More, my faith in God does not require God’s knowing of me. I am “known” simply in my being, along with all of being, and together we are becoming… and becoming… and becoming.

I do not believe that God is “consciously” involved in human life, except that we are a part of God, and we are consciously involved in our own lives. Human Free Will is a part of God. What prevents us from sensing this is our own delusion of division and self… our own conflicted natures. Issues of whether God is omniscient or omnipotent depend upon God having a human understanding of knowing or of power, and I do not believe that to be true. God simply is, and we relate to God because of that.

As one minister/professor colleague of mine has said to me, this theological stance is fairly complex, and inspired by both my understanding of Christian Faith and my experience of Zen Buddhism. It is in part this belief that holds me in Unitarian Universalism, in that it inspires in me my connection to the inherent worth of all beings and the interconnectedness of all existence, two core principles of Unitarian Universalism.

A few years ago, in a communication within the Army Chaplain Corps, I found this statement: “Whereas the Chaplaincy, as spiritual leaders, model faith and belief in the Hand of God to intervene in the course of history and in individual lives;”. Now, I can do some theological circumlocutions and come to a place where I can accept that statement (if not agree with it), those circumlocutions are somewhat intensive. I certainly could not accept it in its obvious, literal intent. For me, God does not intentionally intervene in human history or individual lives… God simply is, and human history and individual lives change and mold in reaction to God’s existence. To paraphrase Albert Einstein, God does not play dice with the Universe, because God is the Universe and all within it.

If a belief in an intervening God who has a personal relationship with individual lives is a prerequisite to be a military chaplain, then perhaps I have some thinking to do about my call to ministry. If, rather, the document that quote was taken from actually is trying to define what the theological center of the Chaplain Corps is, then I accept that I am theologically on the margins but can still find a place. I will, in Unitarian Universalist prophetic tradition, continue to speak my truth, the truth that is written on my heart by my life, by scripture, by the flight of birds and the existence of evil, and let “Einstein’s Dice” fall how they may.

Yours in Faith,

Rev. David

A Case For Religion

June 5, 2012A growing number of people in the United States define themselves as “spiritual but not religious.” Study after demographic study shows that this segment of our population is rising steadily, as people growing up in a pluralistic society reject the rigid dogma that they associate with “religion.” Maybe you’re someone who has claimed this title for yourself.

I’d like to make a case for religion.

To be clear, I, too, reject rigid dogma. I reject narrow-minded thinking that groups together only people who believe very specific things into one “religion.” What I embrace, however, is the notion that spirituality practiced alone is missing something. It is missing the relationships that are necessary for human growth and development. The relationships found in religious community.

Too often, I talk to people who substitute a solitary spiritual practice for religious community. Sometimes, those people think they’re practicing a religion. I ache to let them know what they’re missing.

Meditation on a cushion in the corner is a fine thing to do, but it’s not Buddhism. Prayer—whether you pray by kneeling at your bedside or walking through the woods—is a wonderful way to center yourself on the spirit of life coursing through you, but by itself, it’s not Judaism, Islam or Christianity. All of these religions require something more: the relationships built in communal practice, the accountability of having others who are practicing their spirituality with you, the opportunity to learn and grow based on the experiences and thoughts of another.

Religion requires community. And this is a good thing. The word itself comes, it is widely thought, from Latin roots meaning “to bind together again.” Religion requires being bound to something beyond yourself—it requires relationships.

And human beings are meant to be in relationship with one another. We are not meant to be solitary creatures—we have evolved to need to be part of a group. Again—a good thing.

And religion requires only the binding together of people into a group based upon spirituality.

You wouldn’t know this from the ways in which the word “religion” is used in our society. All too often, “religion” is defined as the way in which one believes in a supernatural God. This is not what religion is.

My colleague the Rev. Mark Morrison-Reed writes that “the central task of the religious community is to unveil the bonds that bind each to all.” It’s not about teaching one right way of looking at the world. It’s not about a specific theology. It’s about understanding our intimate and unbreakable connection to everything else in existence.

Religion is about connection. It is about community. It is about accountability. Religion is about having people to share your spiritual experiences with.

Religion is not necessarily about dogma. My chosen faith, Unitarian Universalism, is a creedless religion. We believe it’s more important for people to be in community with one another than to agree—even about the big things like God or death or salvation.

We learn from one another. We challenge one another. We support one another. Sometimes, we even irritate one another, and our response to that irritation teaches us how to live in the world with people we don’t necessarily like.

But we wouldn’t have any of these things—the good, the bad, the uplifting, the challenging—if we chose the path of individual spirituality.

Sex and War: Thoughts on Memorial Day Weekend

May 26, 2012For Sunday, May 27th, I titled the worship service at the Church of the Restoration, “Sex and War: Love and Hope.” My title mostly came from a 2008 book by Malcolm Potts and Tom Hayden, Sex and War: How Biology Explains Warfare and Terrorism and Offers a Path to a Safer World. It’s a very interesting book, but not what I am thinking about this afternoon. When I arrived at the church today, the lovely man who changes the lettering on our sign had put these words, “Sex and War or Love and Hope.”

The sign startled me. It just wasn’t at all how I thought about the relationships between these four things. Now, like many ministers, I am the kind of person who when surprised by something just starts thinking about it. Some of my family members say (kindly, usually) I think too much about strange things! One of my colleagues recently bemoaned the fact that anything can become a story for a sermon or a blog. We observe ourselves and we observe our own thinking. My friend would like to just be in the experience, and there is certainly something to appreciate about being in the moment, in the flow. In fact, much of spiritual practice is designed to help us to be “in this very moment.” Still, there is also much to appreciate about observing ourselves, especially observing ourselves without judgment but with curiosity.

When something startles us, when two unusual things come together in our minds, we can be opened to creativity, new ways of seeing things or new questions. So, when I saw the sign, I thought, “What was he thinking when he put the word “or” on the sign?” Very briefly, I wondered if I should ask him to change it but thought, “No, it’s kind of provocative that way. What will passersby think that it means?”

I thought that the wording seemed to put a negative implication toward sex. Now, this might be true of some ministers and some churches, but is not at all true for this minister. I think sex is a vital, essential part of life and indeed can not only be deeply loving but also deeply spiritual. Well that thought lead me to think about the relationship between war and love and hope. It seems to me that it is complicated.

I have known loving warriors. I live in Carlisle, Pennsylvania which is the home of the Army War College; colonels come to Carlisle for a year of study. The Carlisle Barracks also houses the Peace Operations Training Institute whose mission is to study peace and humanitarian relief any time, any place. Their mission is in part, “We are committed to bringing essential, practical knowledge to military personnel, police and civilians working toward peace worldwide.”

(www. http://www.peaceopstraining.org/e-learning/cotipso/partner_course/725)

I learned by listening to the colonels. Those colonels who study peace and war are not usually leaders who want to go to war. All of those who go to war often go with love in their hearts: love of family, friends and country. Combat veterans tell us that their actions are motivated by love for their comrades, the “band of brothers, and now sisters,” who are right there beside them. We who stay behind love those who go. We all hope and pray for their safety. We all hope and pray for peace.

Now, my prayer is that there be no more war; my hope that we will all learn to live in peace. My basic stance is that of non-violence and pacifism. I never want people to go to war because they have been intentionally deceived or for corporate profits. But may we never forget the worth and dignity of all, the love and courage of those who go to war and of those who stay behind.

All these thoughts came from seeing the word “or” on our sign, and as it happens, he used that word because we don’t have a colon.

May love, hope and wisdom guide and sustain you.

Rev. Kathy Ellis

The Meaning of Memorial Day

May 24, 2012I thought I understood the meaning of Memorial Day. I thought the military uniform hanging in my closet taught me the meaning of Memorial Day. I thought that growing up the child of a soldier, and the grandchild of a sailor taught me the meaning of Memorial Day. But I was wrong.

Day. I thought that growing up the child of a soldier, and the grandchild of a sailor taught me the meaning of Memorial Day. But I was wrong.

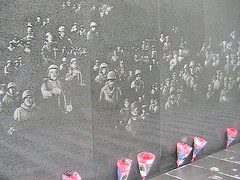

I sensed the meaning of Memorial Day. A few years ago I preached a sermon about standing at the Vietnam Wall with my father, watching him trace names of friends across the wall. It was the only time I ever saw tears in his eyes. I saw my grandfather visit the Punchbowl WWII memorial in Hawaii, and I saw those same silent tears.

I thought I knew the meaning of Memorial Day… but I did not. Not until my wife came and told me that the television news had just reported the death of my friend, military partner, and former roommate in the Al Anbar province of Iraq on December 6th, 2006. It was not until I realized that I too would one day have a name to trace across a memorial somewhere, the name of Travis Patriquin, that I learned the meaning of Memorial Day.

While I do not believe in a spiritual place called hell, I think General William Tecumseh Sherman was right when he said that “War is Hell”. It is a hell that exists in this time, in this world, not in some metaphysical afterlife. I wish with all my heart we could rid ourselves of it… I wish for the day to come when we no longer send our young men and women off to walk through that hell. I wish for the day when our problems are solved by meeting, not by killing. It is rarely those who should be meeting that instead face the killing. I wish with all my heart for what military forces we have to become a tool of peace, not a weapon of war.

Clinton Lee Scott once said “Always it is easier to pay homage to our prophets than to heed the direction of their vision”. The true meaning of Memorial Day is not homage… it is not to honor those who have served, those who have died for our nation. Oh, that is what the media will tell us, what the President will say when he lays a wreath at Arlington National Cemetery in a few days. I expect him to strike a tone of “honor our dead, and standing resolute.” No, it is not honor that our war dead ask of us. Honor is the easy way out of the vision they call us to.

The true meaning of Memorial Day is to remember. It is to remember that the cost of war is almost always too high. The true meaning of Memorial Day is not to honor our dead, but to remember the price they paid. To remember the price their families pay. To remember the physical and psychic wounds that the survivors of war, on all sides, carry with them till the end of their days. To remember the lives never lived. To remember the horrors unleashed upon civilian populations by the tools of modern warfare. To remember…

I want to cease thinking of Memorial Day as if it were a holiday, for it is not. I want to end the Memorial Day sales and the picnics, the trips to the lake and the hamburgers and hotdogs with stars and stripes napkins. We should never “celebrate” Memorial Day. I want Memorial Day not to be a holiday, but rather a National Day of Mourning.

It began as “Decoration Day”, a day when families and friends would go to cemeteries and place flowers and flags upon the graves of those who had died in the Civil War. From those graves they heard, and they remembered the cost of war. I want to return to that spirit, so that the memory of the true costs of war is fresh in our minds, renewed annually… so that perhaps we can honor our dead by sending no more to join them.

Keep your Memorial Day plans, if you have them, but remember the “reason for the season”. We do not honor the casualties of war with flowers and speeches, but by truly and deeply remembering the cost of war when we contemplate sending our service members of today into harm’s way. We honor them by remembering that war is a hell that should rarely, if ever, be unleashed.

Remember.

Yours in faith,

Rev. David Pyle

www.celestiallands.org

Chaplain, U.S. Army Reserve

Changing Your Wiper Blades

May 16, 2012Last week I bought new windshield wipers for my car and I was amazed at how much better I could see! These new wipers were like a miracle – with just a few strokes they swiped the windshield clean, giving me a clear view of the road ahead. For weeks I had been driving with impaired vision without even realizing it. I just assumed that everyone looked out windshields like mine, through streaks and skips and stripes, straining to see in the sun’s glare. It’s hard to say exactly how long my sight had been compromised because it had deteriorated so slowly, over a long period of time. This got me wondering what else in our lives might be performing less than optimally without our noticing.

There is a theory that says if you drop a frog into a boiling pot of water it will immediately hop out, but if you were to put that same frog into a pot of cold water and slowly heat it up, the frog will stay put, not noticing the heat or the danger. Now, I’ve never tested this hypothesis – and I have some serious ethical questions for those who have – but I can see the truth in it. I think it’s natural to become so familiar with something that we don’t notice subtle, but ultimately substantial, changes. We think we’re doing just fine when, before we know it, the water is boiling beneath our feet. If we’re not careful, long-standing relationships can erode as patterns of behavior ingrain themselves, diminishing our view of those around us. Our beliefs and opinions – our faith – formulated in our distant past and clung to with unexamined, habitual resolve, can fall prey to this fate as well. So, what are we to do? How do we avoid a frog’s fate?

It’s mostly up to us to notice when our view is getting cloudy. We all need to change our wiper blades from time to time, and much more frequently than we may think. When we do, we’ll see the road more clearly, with all its attendant dangers and abundant opportunities. Sometimes, if we’re lucky enough, someone – a trusted friend or a family member – may point out that our view has somehow gotten murky. A child comments that we’re bringing too much work home from the office. A hymn at church unexpectedly brings tears to our eyes. Or our partner utters those ominous words: “We need to talk.” Such windshield-wiping moments can be challenging, but they can also show us how beautiful the journey can be when the view is unobstructed. They can remind us of the miracles that happen when we are in relationships with those who see us clearly, even when we’ve lost sight of ourselves.

This day and every day, I wish you peace.

Peter

A Wild Patience

May 9, 2012Rev. Dr. Michael Tino

A wild patience has taken me this far/as if I had to bring to shore/a boat with a spasmodic outboard motor/old sweaters, nets, spray-mottled books/tossed in the prow/some kind of sun burning my shoulder-blades. -Adrienne Rich, Integrity

Patience is a spiritual virtue worth cultivating, and yet it is something in short supply in my life right now. Last night’s news from my former home state of North Carolina is just the latest in a long string of insults to all people who believe that love is love. And as a gay man of faith, a part of my heart is torn out every time another vote is taken to declare my love to be inferior.

It’s hard to muster patience when your civil rights—or the rights of those you love and care about—are on the line. It’s hard to muster patience when the list of states banning same-sex marriage in their constitutions steadily grows and grows. It’s hard to muster patience when lawmakers fail again and again to have the courage to pass even simple legislation to, for example, ensure workplace non-discrimination for LGBT people.

It’s hard to keep repeating to myself Theodore Parker’s assertion from so long ago that “the moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” That quote has long been a mantra of mine and yet with every passing election, with every legislative session, with every disappointing vote, it becomes harder to say, harder to believe, harder to force myself to think about.

And yet with every vote, it becomes more important to say. It becomes more important to remind myself of the truth in that statement. It is as if I am breathing necessary oxygen on the ember of hope that burns within me, keeping it glowing so that it might one day become a flame. And so, I practice patience.

And then today, our President announced that his “evolving” views on same-sex marriage had evolved some more. Did I hear this correctly? The President of the United States contradicted 61% of the voters in an important swing state? Maybe that moral arc of the universe will bend towards justice after all.

And so it is that I realize that what needs to be cultivated is not mere patience, but a wild patience.

A wild patience that knows when it’s time to wait, and when it’s time to act. A wild patience that sits sometimes, spreading healing balm on burned skin, and gets up sometimes to build, to work, to do. A wild patience that knows the difference between faith and resignation, that keeps the ember glowing amidst the howling storm, that steers the boat toward the shores of tomorrow.

Yes, hope is here. Love and justice are coming. Their arrival requires patience. Their arrival requires waiting, and breathing, and letting things go. And it also requires hard work.

May we find in ourselves both the patience to wait and the impatience to do what must be done. This year, let us be wildly patient together.

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210