Choosing When to Pray

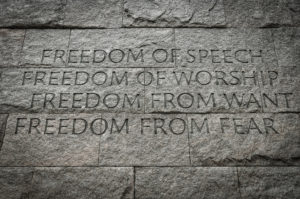

November 1, 2016Prayer is an important part of the spiritual lives of many UUs—but we also are clear that people need to choose for themselves how and when they will pray. It isn’t the government’s place to decide that for people.

In the early 1960s the UU Schempp family helped to make that clear in American law. Sixteen-year-old Ellery Schempp wasn’t comfortable with having to say the Lord’s Prayer and listen to Bible readings at his public school. His parents, Ed and Sidney Schempp, talked about the issue with Ellery and his siblings Roger and Donna. Together they decided that not only was it not right for Ellery to have to say a prayer he didn’t believe in, no kid should be required to say a prayer that didn’t match their beliefs or faith tradition.

So the Schempps challenged the school in court, and their case went to the Supreme Court. In 1963 the court ruled in Abington Township School District v. Schempp that it was unconstitutional for a public school to expect students to participate in school-sponsored religious activity. The 1st Amendment of the US Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, and a UU family stood up to make sure that children were included in that guarantee.

What Healing Looks Like

March 30, 2014I remember as a teenager, home alone one afternoon, listening over and over to David Bowie sing “Is there Life on Mars?” while gazing at the cover of his Hunky Dory album. I longed to be able to articulate the feelings I had inside me, and somehow this British man wearing makeup came closer than anyone else I’d yet encountered. I remember wondering– if my mother listened to him sing “Is there Life on Mars?” would she at least partially understand the desperation, the hopelessness, the profound alienation I felt all the time? I never dared to ask her. My friends and I got high instead of talking honestly about it all.

I didn’t know yet that I’d come to identify the vague loneliness and misery I felt all the time as heavily influenced by sexism and racism, classism and homophobia, in a declining Midwestern industrial town. I didn’t really get yet, that there were problems that were systemic, that the tiny lives of my friends and me were part of a much larger picture. It wasn’t till I was a young adult, beyond the reach of parents and school systems, accompanied instead by friends who deeply saw and heard me, that I could begin to name the parts of who I was and what I knew.

Last night I went to the “Be Heard Minnesota Youth Poetry Slam Series, 2014,” sponsored by a group called TruArtSpeaks. I saw there a group of young people who have found their voices, and who are speaking and heard at the intensity level I longed for myself as a teenager.

What happens when adults like Tish Jones, the Executive Director of TruArt Speaks, devote their lives to making young voices heard? When their coach Khary Jackson (AKA 6 is 9) takes time to work with them to express themselves clearly and with passion? When a packed house of family, friends, and strangers at a local theater pays and cheers and tells them they have changed us by speaking their hearts?

This is what healing looks like, I found myself thinking, even with wounds that are still gaping, in a world of oppression and violence and addiction and all of the other reasons that these kids and other people suffer. This is where healing begins.

Seven out of the nine contestants were young women of color. They, and the two young men—one African American, one white and openly gay–spoke about the ravages of racism and sexism and homophobia in their lives, of parents who are absent or abusive, of schools designed for them to fail. And there we were, a cheering, clicking, community of support, hanging on their every word. What does that do to a young person, I wonder.

For me, as an adult, as a white person, as a person with power and privilege in the culture, such an encounter also means healing. My healing begins with listening, and believing, young people, and marginalized people, the way I wanted my own mother to hear me. It begins with paying attention. And it extends to supporting the organizations and leaders who elicit these voices, in understanding that without people like Tish Jones and Khary Jackson, the safety to tell stories in that theater would not have been present for the young people on the stage.

This is what healing looks like. Led by the courageous, the ones who speak truths denied by louder voices, supported by love and respect. This is what healing looks like.

I feel profoundly blessed to have attended the slam last night, and to be represented as a Minneostan by the six young people who will move on to the national levels of competition as spoken word artists. But, as the MC kept saying over and over last night, This isn’t about competition. It’s about community, and leadership development, and having a good time together. And we did.

UU Verbs

August 10, 2013I had the honor of spending this week with a dozen youth who chose to spend the first week of August in New Orleans. So you already know that they are brave. You should also know that they are leaders and followers, conveners and collaborators, organizers and educators. But this isn’t a note about nouns. This is a note about verbs. Unitarian Universalist Verbs.

My colleague, Rev. Paul, showed up (consistently, faithfully) this week wearing these verbs around his neck:

CARE

SHARE

GROW

LEARN

HEAR

HOPE

LOVE

I want to take a moment and affirm the National Youth Justice Training UU youth for embodying these verbs with courage and kindness beyond measure. Let us join Jessica, Emma, Emily, Emily, Meiling, Alex, Ellie, Ian, Sam, Sam, Anais, and Leah in transforming the injustices of this world into Beloved Community that both is and is becoming.

May it ever be so, beloveds.

Renew Your Membership

We invite you to join your fellow CLFers to renew your CLF membership and stewardship of the CLF for another year.

Support the CLF

Can you give $5 or more to sustain the ministries of the Church of the Larger Fellowship?

If preferred, you can text amount to give to 84-321

Newsletter Signup

About

Quest for Meaning is a program of the Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF).

As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.

Contact

Church of the Larger Fellowship Unitarian Universalist (CLFUU)

24 Farnsworth Street

Boston MA 02210